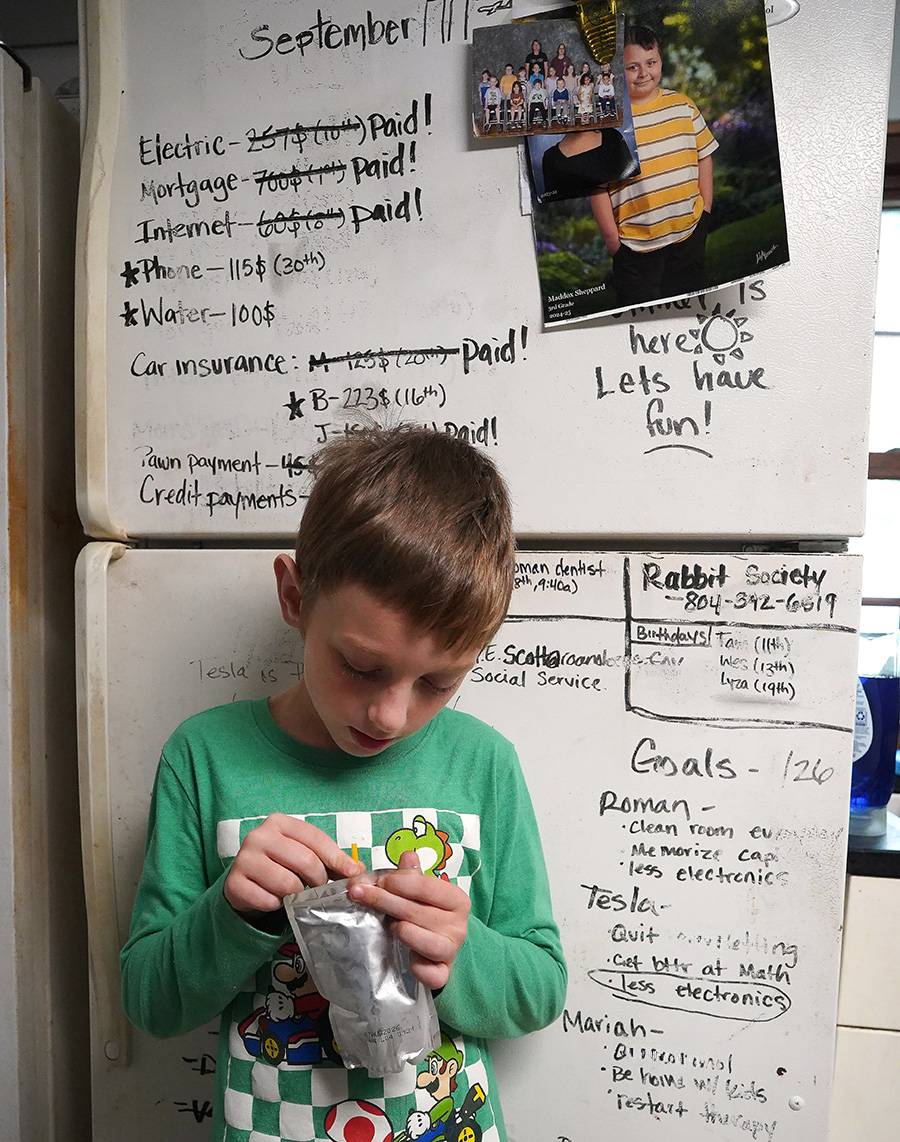

Six months after purchasing the wood-frame house in southeast Roanoke, Virginia, Mariah Widener says she still marvels at the idea that she owns the place.

For months, she worked back-to-back full-time jobs, grabbing half-hour naps in her car between shifts, to afford the down payment on the $70,000 three-bedroom home. The 115-year-old structure had been condemned before Widener and her fiance, Bradley Epperly, convinced the bank that they could transform it into the perfect home for their family of five. It still needs a fair amount of work, but Epperly, a mechanic by trade, has painstakingly removed mold, hung new drywall, and replaced flooring to fulfill the couple’s dream of home ownership.

Widener, 29, was born and raised in the community. For most of her childhood, her family bounced between rentals, hotel rooms and temporary shelters. They were staying in one such shelter about 15 years ago, after a fire burned down their rental home, when members of Central Church of the Brethren came to visit.

A small group within the church had spent the previous five years studying hunger, homelessness and generational poverty before deciding they were ready to apply what they’d learned by helping a local family. Widener recalls what happened next as the most stable period in her childhood. For about four years, Central helped the family cover rent and utilities, assisted with car repairs, and mentored Widener and her two younger brothers.

That stability wasn’t forever, and Widener’s parents have continued to struggle on and off. But it was long enough to show her that life could be different.

“They have changed the trajectory of the way my life would’ve been,” Widener said. “I needed all these nice, responsible people showing me the way. They taught me how to break that cycle of living paycheck to paycheck and always being broke.”

How do your ministries honor the agency of the people you serve?

Widener’s accomplishment has been cause for celebration within Central’s tiny congregation, proof that even a small number of individuals can make a big difference if their mission is focused and long-term. But the century-old church hasn’t been going it alone.

Central is a founding member of Southwest Congregations in Action, a coalition of seven congregations that banded together roughly 20 years ago to serve as a de facto parent-teacher association for a nearby elementary school with a large number of disadvantaged students. Since then, volunteers with Congregations in Action — or CIA as it’s more commonly known — have done everything from serving as room parents and field trip chaperones to addressing larger concerns with the school’s families.

Every Thursday, volunteers from one of the CIA’s congregations gather in the cafeteria of Highland Park Elementary to pack bags full of snacks for the most economically insecure students to take home for the weekend. Central Church of the Brethren contributes fresh produce to those packages weekly.

The church has also traditionally sponsored an individual through the Brethren Volunteer Service (BVS) to organize the school’s Pack-A-Snack program and help at the school wherever assistance is needed.

“My job description is, ‘Yes, E, all of the above,’” said Aly Heckeroth, 23, who served as a BVSer at Highland Park during the 2024-2025 school year. A Bridgewater College graduate, Heckeroth is the 10th Brethren Volunteer Service associate that Central has hosted and made available to Highland Park.

While there, Heckeroth worked with students on counting, grammar and reading skills, and also handled some administrative tasks. Heckeroth, who hopes to be ordained someday, found the experience enlightening.

“If I want to be a pastor in a church, I have this great model of how you do outreach in the community,” she said. “Central is definitely full of people who care and who are willing to put in the time. They definitely wish they could do more, but they’re realistic in their capabilities.”

‘Leap of faith’

In Central’s heyday, at least 300 people packed the pews on Sundays, said lifelong member Bob Iseminger, chairman of the church’s board and its organist. Nowadays Central has somewhere between 125 and 150 members, with roughly 25 to 30 on Sunday.

That’s about half the number of active members Central had when it initially started studying the roots of poverty two decades ago. Members of the church’s Faith in Action group read books like Barbara Ehrenreich’s “Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America.” They discussed what they read, watched films and “got comfortable with the topic,” recalled longtime member Jennie Waering, a retired federal prosecutor.

“Then we decided to take a leap of faith,” Waering said, and put all their studies into practice.

Widener remembers being a freshman in high school and home by herself one day after school when the girl who lived upstairs in the other half of the rented duplex pounded on the door to let her know the building was on fire. She recalls grabbing her guitar before running to take refuge across the street. And she remembers her parents and younger brothers pulling up to the burning home, fresh from a trip to the library, and her father trying to push his way past the firefighters, fearful his daughter was still inside.

Her memories of life after the fire are hazier, but Widener recalls that her parents were struggling to get back on their feet when they encountered the group from Central, including Waering. A fiercely independent teenager, Widener initially resisted the help they offered. But she figured if her parents could swallow their pride, she could too.

She also noticed something else — that the members of Central never made her feel less-than and never judged the family for any of the challenges they faced. They simply helped, and not just with finances, but with time, compassion and good advice.

After the church helped the family secure another rental, Waering took Widener shopping to pick out bedroom decor in pink and light green, “all the way down to the curtains,” recalled Widener. “I had stuff again. It was so important to me.”

How much does your congregation know about the underlying causes and dynamics that impact the people your key ministries serve? How might you learn more?

Vicky Chapman, who joined Central more than 35 years ago, said the church’s Faith in Action group had learned from its studies that it needed to set realistic expectations for its work addressing homelessness. The church would assist only one family at a time, preferably one with children at Highland Park. Everyone understood that the challenges of generational poverty would not be resolved overnight, she said. They could provide some financial assistance, helpful advice and healthy relationships — but they’d have to leave room for people to make their own decisions and mistakes.

“That’s important because we’re not going to ‘fix’ someone,” Chapman said. “Poverty is so complicated. People have to have their own plans, and the only thing we can help them with is their own plan.”

With help from Central, the Wideners managed to remain in their rental home for four years, enough time for Mariah to graduate from high school.

“We kept those children in a home several years, and that had to be a success,” Chapman said. “If the children have some stability, it makes a difference.”

The families Central works with are often recommended to them by the school social worker or a local homeless assistance program. Church members try to help families address the problems contributing to their instability by referring them to community programs and relying on their own expertise. The effort, Chapman said, has revealed that Central’s small membership has talent, with expertise in law, finance, education and public benefits — all of which has been put to good use.

She and Waering acknowledge that it can be frustrating when someone ignores advice or makes poor choices. But it’s important to realize that change may come slowly, particularly for those experiencing generational poverty. Several church members with a background in finance recently helped a woman file four years of old tax returns, after which she received a refund of several thousand dollars. However, she declined advice about how to manage that money and is again struggling to pay her bills.

“One of the things you have to realize is you can help people, but they have to decide how you help them,” Waering said. And sometimes, she added, the impact of your efforts isn’t immediately apparent.

By focusing on families with children, Waering said, “You may not have done anything for the parents, but you might have made a huge difference for the children.”

‘It has to be a commitment’

Meeting the needs of children has long been the focus of Congregations in Action, which primarily serves the students at Highland Park. The school draws students from all over the city, and in the past, that made it difficult for parents from far-flung neighborhoods to participate in the PTA, said Brooke Blanks, the school’s principal. CIA volunteers stepped in for about a decade to support teachers and students in the same way a PTA ordinarily would. Nowadays, the parent-teacher organization is robust, but the CIA has continued to help.

The organization stocks a school clothing closet, delivers lunches to teachers, provides hand-knit scarves and hats for the children each Christmas, and staffs a Fun Day celebration — complete with a bounce house and a dunking booth — following standardized testing. If a child is struggling in the classroom, Blanks said she calls on Iseminger, a retired educator, “and he comes and just does amazing, magical things.”

What does your church need to stay invested in the long term? How might you rightsize expectations and effort to avoid burnout and discouragement?

“When I say, ‘I need volunteers,’ the next thing you know, I’ve got retirees showing up saying, ‘I can teach geometry in Spanish.’ The time they give is unparalleled,” Blanks said. “The beautiful thing about the CIA is they have no skin in this game at all other than to serve. It just works because nobody brings their dogma in here. They just bring a willingness to help.”

Alice Holman, chairwoman of the CIA and a member of Second Presbyterian Church, said each congregation appoints a representative to the group, which meets monthly with Blanks to identify the school’s needs. Then each member returns to their congregation to see what they can provide. Second Presbyterian budgets about $2,500 annually, primarily to purchase Pack-A-Snack supplies, but worshippers sometimes earmark additional offerings for Highland Park.

At Central, Waering estimates the church spends about $50 each week on fresh fruit for Pack-A-Snack bags; a grant from the Kiwanis as well as member donations cover that cost. In addition, Central received a grant of nearly $2,400 from its denomination in 2019 to help cover additional protein, like shelf-stable milk, peanut butter and Vienna sausages. Because of school closures during the pandemic, the church still has some of that money.

Holman, who has served with the CIA for the last seven years, said the organization is “cross-political and cross-denominational” and “a fantastic example of how congregations can get involved in their communities.”

“It’s always been such a neat group of people, and their foremost thoughts and desires are to help these children in any way we can,” Holman said. “You’ve got to come from congregations with a giving spirt that are very mission-focused. It has to be a commitment. We just see a need, and everybody finds a way to meet it.”

Who is working toward the same goals as your congregation and could benefit from additional support? How might you offer it?

An invaluable partnership

It’s the second Thursday of the month, and at Highland Park, Heckeroth wheels a trolley full of donated food into the school cafeteria where a contingent of CIA volunteers from Second Presbyterian fills bags with cartons of grape juice, cans of chicken noodle soup, packets of fruit gummies and fresh fruit. Central’s Chapman is partial to green bananas, which last longer, but clementines were on sale at Kroger that week, so she dropped off several crates.

All of the children in Roanoke City Public Schools are eligible for free breakfast and lunch, and about 70% of Highland Park’s 350 students take advantage of that, according to Virginia Department of Education statistics. About 50 students, identified by the school, take home a Pack-A-Snack bag each weekend.

Like other members of the Brethren Volunteer Service before her, Heckeroth organizes the Highland Park’s food closet, letting the CIA member congregations — six churches and one synagogue — know when supplies are running low. The Kansas City, Missouri, native grew up in the Church of the Brethren and said she always figured she’d join the BVS; her grandfather had served in the program as a volunteer school bus driver in Texas. She became a BVSer after graduating from college in 2024.

Each year, BVS links dozens of volunteers with communities in the U.S. and abroad, providing a $250 monthly stipend as well as food, housing and insurance in return for a year of service on projects that advocate for peace and justice, support the marginalized, and care for creation. Volunteers don’t need to be members of the Church of the Brethren, and only four of the 10 that Central has hosted have been.

Heckeroth recalled being overwhelmed on her first day at Highland Park, especially as she tried to settle down a room of rowdy pre-kindergarteners. She’s grown a lot since then, she said, and has enjoyed seeing the children she has worked with progress academically. She recently signed up for a second year with BVS, this time working in Elgin, Illinois, with the Church of the Brethren FaithX program.

“It’s certainly a way to humble yourself a little bit. And it provides a little bit of perspective on how other people have to live,” Heckeroth said. “It forces you to be intentional about the money you spend, the actions you’re doing and the difference that you’re making.”

BVS was not able to send a volunteer to Roanoke for the 2025-26 school year. Several of the volunteers previously hosted by Central hailed from Germany, and Germans who expressed interest in coming this year were concerned about the political climate here and whether they’d have trouble with their visas, Chapman said.

Blanks, the principal, said she was grateful for Heckeroth’s assistance, which included filling in temporarily as the school secretary in addition to tutoring students, chaperoning field trips and supervising recess. She said the entire CIA partnership is indispensable to the school.

“Overall, what the CIA provides for us is really anything we need,” Blanks said. “They don’t want anything from us. They just want to help. It’s a partnership that I value above just about everything else.”

The members of Central Church of the Brethren say they’re under no illusion that they’re going to end homelessness and hunger in Roanoke. But they’re committed to investing in their neighbors and doing what they can, for as long as they can.

“You have to be willing to do as Jesus said: Get out there and do it,” Waering said. “That’s what drives us.”

To this day, Waering is listed in Widener’s phone as “Mama #2.” Central members attended Widener’s 2014 graduation, threw a baby shower for her first child, and continued to offer encouragement — and occasionally constructive criticism, Widener said. She recalled that in her late teens, she often quit jobs without thinking about the long-term consequences.

“They’d say, ‘That’s not how you’re going to get anywhere,’” she said. “I’m glad they didn’t give up on me. Going to their church and watching how all of these people are living their lives taught me to be more responsible financially.”

She said she hopes to pass down some of those lessons to her three children. Widener said she always wanted a house of her own so she could record her children’s growth spurts on a wall or doorframe, something she does now at the entry to the family’s kitchen.

“Sometimes, I find myself walking through the home saying, ‘Man this is my house,’” Widener said. “When it hits you, it really hits you.”

Which kinds of partnerships are already present in your work? Who is one conversation partner who could help you think about deepening partnerships in new places?

Questions to consider

- How do your ministries honor the agency of the people you serve?

- How much does your congregation know about the underlying causes and dynamics that impact the people your key ministries serve? How might you learn more?

- What does your church need to stay invested in the long term? How might you rightsize expectations and effort to avoid burnout and discouragement?

- Who is working toward the same goals as your congregation and could benefit from additional support? How might you offer it?

- Which kinds of partnerships are already present in your work? Who is one conversation partner who could help you think about deepening partnerships in new places?