At an airy school site in southeast Washington, D.C., several children gather around an outdoor planter filled with espresso-colored dirt. It’s about 3:30 on a bright summer afternoon, and the students have been there since morning.

They began the day with harambee, a high-energy ritual that lets students pull together and celebrate themselves, before going into a sewing exercise and then a nutrition lesson. Now comes the gardening, where they learn a handy fact — how lavender can repel mosquitos — and start to grow their own plants.

As these students — known here as scholars — congregate, a college-age instructor (also known as a servant leader) watches over them while parents and other site staff linger outside and inside the school.

All of this is part of a Children’s Defense Fund Freedom Schools six-week summer session. And since CDF’s mission is “to ensure every child a healthy start, a head start, a fair start, a safe start and a moral start in life and successful passage to adulthood with the help of caring families and communities,” this program is key.

In fact, CDF Freedom Schools, also offered as after-school programs, are the “heart and soul” of what the Children’s Defense Fund is doing for children and their well-being, said the Rev. Dr. Starsky Wilson, CDF’s president and chief executive officer. Through CDF’s partnerships and work with children, families and communities, Wilson said, the program “helps us to prioritize what we’re speaking about, what we’re advocating around, and the policies we believe families need to create the conditions for their children to thrive.”

A program with history

CDF has a record of helping communities. Civil rights pioneer Marian Wright Edelman, credited as the first Black woman admitted to the Mississippi Bar, founded the nonprofit in 1973 after dedicating her early career to defending the civil liberties of people who faced poverty and discrimination.

Today, the CDF Freedom Schools program is offered to students in kindergarten through 12th grade around the country in community centers, schools, juvenile justice centers, churches and other settings. In 2021, more than 7,200 scholars participated in programs in 26 states and 75 cities.

Freedom Schools have their origin in the Mississippi Freedom Summer project of 1964, which gathered college students to work for justice and voting rights for Black citizens. Back then, these college students volunteered to teach younger students traditional subjects like reading, math and science, along with Black history, constitutional rights and other topics not covered in Mississippi public schools, said Kristal Moore Clemons, the national director of CDF Freedom Schools.

How does your congregation nurture the holistic well-being of children and families in your community?

The early Freedom Schools were established to build the next generation of voters, Clemons said, noting that leaders thought that if they could “crack” Mississippi, they could do the same with other Southern states.

“Our faith-based partners have always played a role in the movement,” she said, explaining that most of the original Freedom Schools operated in churches or community centers.

CDF started its Freedom Schools program in 1995 to help children who lacked access to high-quality literacy programs. Each year, many students — especially those from historically disadvantaged groups — experience summer learning loss. Recent literature on this loss has been mixed, according to a 2017 Brookings Institution report, but one theory cited in the report suggests that lower-income students might learn less over the summer because “the flow of resources slows for students from disadvantaged backgrounds but not for students from advantaged backgrounds.”

To support students, the CDF model has five components: high-quality academic and character-building enrichment; parent and family involvement; civic engagement and social action; intergenerational servant leadership development; and nutrition, health and mental health.

How can partnering with a large national project like CDF’s Freedom Schools empower your faith community’s commitments to the young?

Since its start, more than 169,000 children have experienced Freedom Schools, and more than 19,000 young adults and child advocates have been trained on the model, which offers a research-based and multicultural curriculum. The majority of students in 2021 identified as Black/African American (68.4%), with the second-most represented group identifying as Hispanic/Latino (13%).

Because the schools are free to families, parents and guardians don’t incur the expenses they might otherwise have for child care, camps or academic programs. This can be especially helpful in low-income communities.

A vital part of a big mission

School systems vary state to state, and there can be battles over what is offered in the classroom. For instance, some schools now are dealing with banned books and debates about critical race theory, among other issues, Clemons said.

Children also continue to face changes within the system, such as periods of distance learning and isolation, because of the COVID pandemic. Some students are dealing with news of school shootings and racial injustice as well.

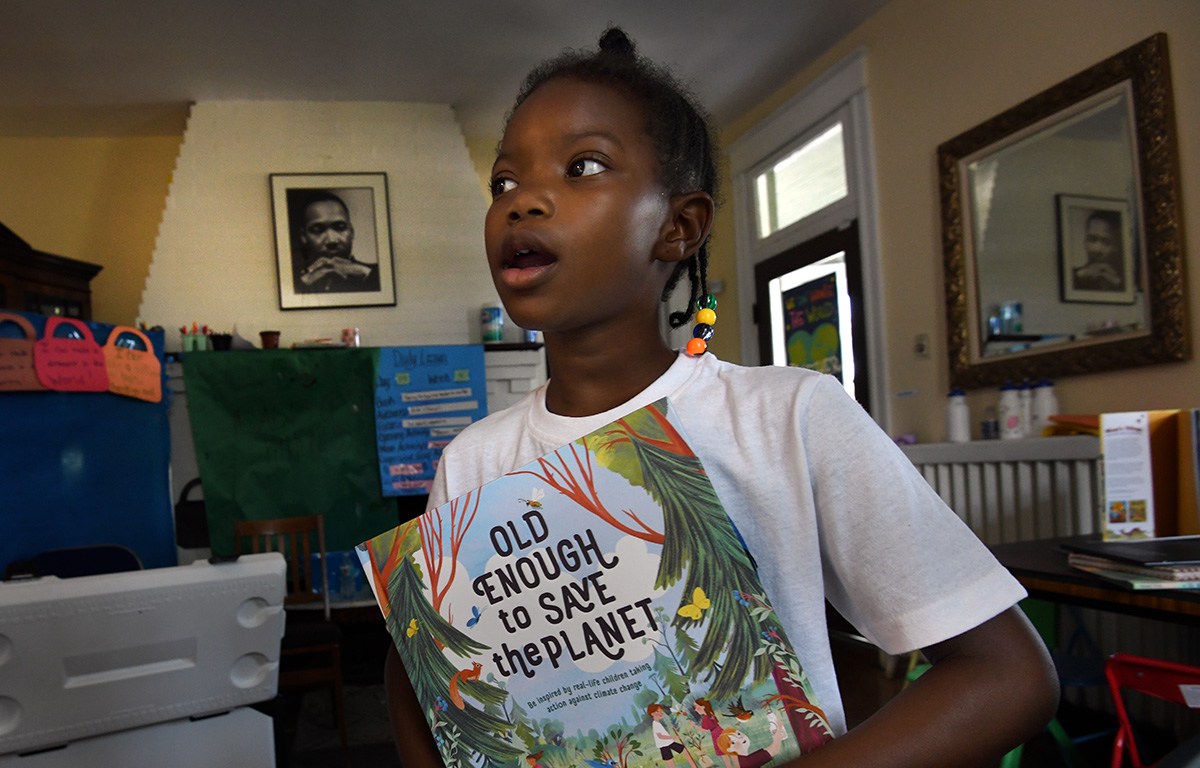

“Every year, we choose a different issue that scholars across the country will organize around and take action on,” said Wilson, the CEO. “This year, we’ve chosen climate justice, because we recognize that the planet is a place that our young people will inherit and that climate justice is racial justice.”

How do the five components of CDF’s model speak to your faith community’s theological understanding of discipleship and the formation of children?

Scholars come together, discuss the issue and share their ideas for solutions on coordinated National Days of Social Action — and they’re allowed to dream, said Joy Masha, program director for the Washington, D.C., CDF Freedom Schools. Scholars might propose a rally, a call to action to a state council member or the creation of more programs for children in their community, among other means of advocacy.

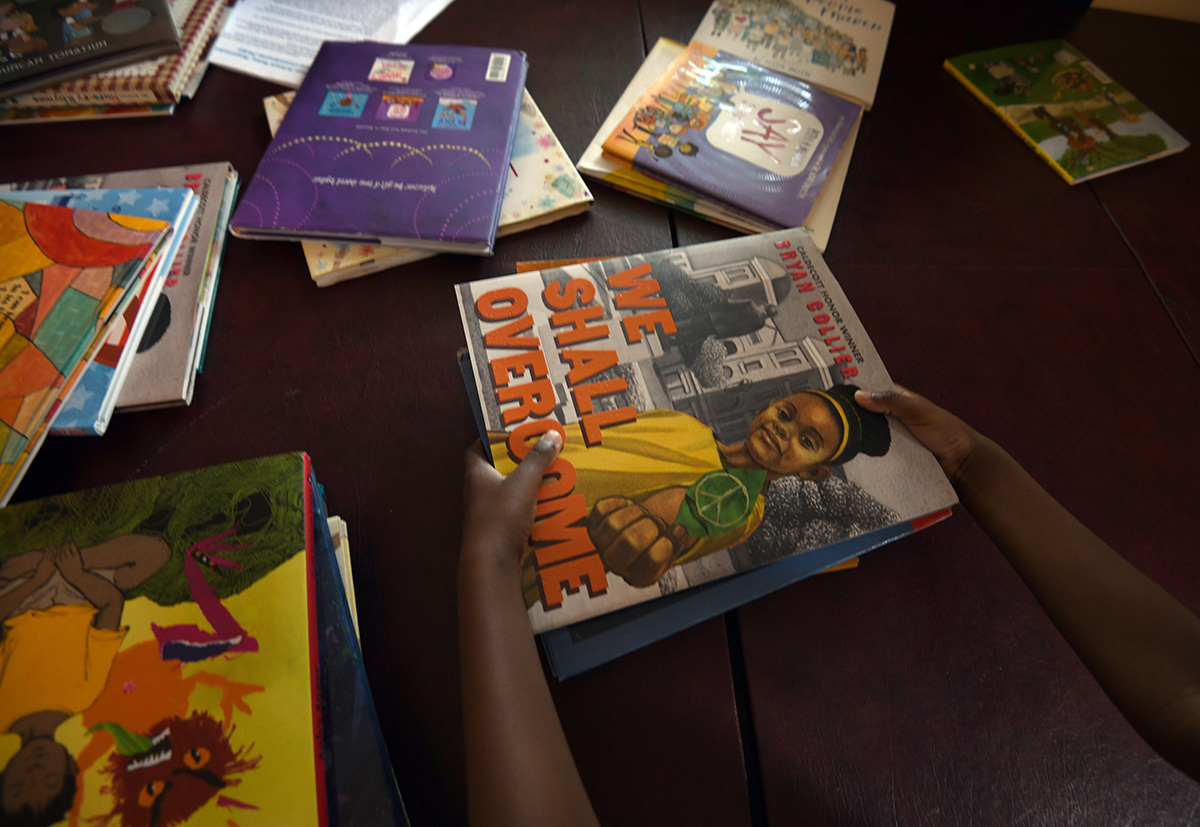

Because educators may not be able to deviate from state curriculum requirements tied to testing, Freedom Schools historically have supplemented content that traditional teachers could not offer, Clemons said. That includes books featuring people of color — important since fewer than 27% of children’s books published in the United States feature nonwhite children, according to CDF — and educating scholars about figures in history.

How does the Freedom Schools model activate young people on issues that matter to them? Why might this matter to your church?

“We don’t want to be controversial. Freedom Schools are not here to break down the status quo. We’re here to be in community with people,” Clemons said.

“We’re here to show children that [if] you want to be a scientist, great. If you want to be a yoga instructor, great. If you want to be the next vice president — because we have books on Kamala Harris — you can do that.”

Some parents say they appreciate the programming and the ability to participate via weekly meetings. Rochelle Gibbons has two children enrolled in the D.C. summer program. If she were to send them to camp instead, they’d simply play, she said. But here they read and build relationships as scholars.

Another D.C. parent, Ashley Jones, said she also appreciates the model. Freedom Schools staff care about the children and the environment that families live in, she said, and teach children that they’re not too young to make a difference.

That lesson is big. Because children are listening. Processing current events. And sharing their thoughts.

Gibbons’ daughter, Dyllon-Rose Gaskin, did just that after her mother spoke at a recent parent meeting in the classroom. The 10-year-old scholar said the program allows her to read books every day and discover new words.

“I learn a lot,” she said, explaining that she’s finding out “interesting stuff” in a fun way.

“Miss Joy has a strong voice, and it helps me speak up sometimes,” she said of Masha’s work at the site.

So what exactly would she speak up about? Dyllon-Rose simply said, “I would speak up about, like, gun violence and different things around the world, like homeless[ness].”

How does it feel to know about these issues as a child?

“People are getting killed … every day, and that’s sad, because people are losing their lives for no reason,” Dyllon-Rose said.

Looking toward a happier future, she shared her desire to be a teacher, a hand model, the vice president, a mayor and “a lot more.”

This kind of exchange, where scholars discuss a range of subjects, is not unusual.

After years of working in the space, Masha said she understands that age does not necessarily determine a child’s experience. Gun violence was the scholars’ issue for 2021.

“As we see more gun violence here in D.C., we know that we can have these conversations with our young people, because our model allows us to do that,” she said. “So if gun violence is a topic that young people want to not only talk about but address, then we explore that solution with them and help them put it into action.”

Within integrated reading curriculum lessons, Freedom Schools use books to explore particular issues and allow scholars to analyze each plot and connect it to the community. Schools also offer parents resources for talking with children about these issues.

The faith connection

To make an impact, CDF partners with various institutions and organizations. To run a program, would-be executive directors apply on CDF’s website and learn about the training, fiduciary and programmatic requirements that accepted sponsor organizations must maintain.

CDF recommends that, at a minimum, facilities be licensed to serve children. Programs then do their own fundraising to bring Freedom Schools sites to fruition, with CDF recommending that programs cover costs for at least 30 scholars.

Since faith communities have a long history of social action and advocacy work, this connection continues to resonate.

Wilson, who also serves on the Duke Divinity School board of visitors, references Jesus’ words with respect to CDF’s work and notes that defending children is “a religious commitment that is resonant with the call of the Christ.”

“For an audience of clergy, I say, ‘If Jesus did not walk among us, then Jesus has less capacity to connect with us,’” he said. “The God that I serve is one who took up flesh and walked with humanity.”

It is this walk that others also highlight.

The Rev. Dr. Van H. Moody II, founding pastor of The Worship Center Christian Church in Birmingham, Alabama, said his church has offered Freedom Schools for several years. He said children in communities of color may not have access to early childhood education, which can put them “behind the eight ball” when they start school. Added to this, summer learning loss can have cumulative effects. But Freedom Schools can help.

“It’s a beautiful program that really checks a lot of boxes that we’re passionate about,” Moody said, noting that it helps kids grow academically, helps them become more well-rounded because they gain a historical foundation, and helps empower them to become conscious changemakers.

His church began supporting the program through funds dedicated to missions, and in recent years has funded it via an endowment, along with public and private partnerships.

“Our faith informs us about how important it is for us to make sure that the next generation not only knows God but that they are prepared to continue to really stand on the shoulders of the preceding generation and to carry the mantle forward,” Moody said.

Birmingham has both a high murder rate and a high violence rate, and many kids are coming from communities where they haven’t seen themselves in a positive light. With these schools, the pastor said, scholars can see the possibilities of what they can be.

“In the Old Testament, the nation of Israel is often taught to talk about the goodness of God and their faith principles with their children and their children’s children,” Moody said. “For us, pouring into the next generation, making sure that the next generation is educated … and prepared to live their best life and affect society in a positive way is an extension of what we believe God has called us to do.”

What can your congregation learn from the Freedom Schools model of formation and community engagement?

Questions to consider

- How does your congregation nurture the holistic well-being of children and families in your community?

- How can partnering with a large national project like CDF’s Freedom Schools empower your faith community’s commitments to the young?

- How do the five components of CDF’s model speak to your faith community’s theological understanding of discipleship and the formation of children?

- How does the Freedom Schools model activate young people on issues that matter to them? Why might this matter to your church?

- What can your congregation learn from the Freedom Schools model of formation and community engagement?