A barely noticeable blip in the nation’s consciousness as 2020 began, COVID-19 by March was a full-blown emergency, triggering mass shutdowns, widespread disruption and general havoc.

In Wake County, North Carolina — as in communities across the country — families who relied on the Free/Reduced Meals program to provide healthy food for their children were suddenly without as schools closed their doors.

County officials had long ago recognized the necessity of delivering food to low-income families during the summer, when schools were not in session. They had a program in place for that.

But could they avoid disruption to this vital service during a sudden, pandemic-driven shutdown?

It turns out that they could. But it took an all-hands-on-deck collaboration among an existing coalition of government agencies, nonprofits, businesses, churches and other faith communities to make it happen.

“When the pandemic hit, we were ready,” said the Rev. Stephanie Workman, associate pastor at Kirk of Kildaire Presbyterian Church in Cary, North Carolina, and a leader in the effort.

Within a few days of the schools’ closure, the summer food program pivoted to provide meals to low-income families, she said. By the end of August 2020, they had distributed 154,000 meals. One participant likened it to a “biblical miracle.”

Is your congregation ready as the pandemic continues? Could you retool or expand existing ministries to become ready?

Since 2015, an array of organizations had been building an infrastructure to serve the vulnerable — part of what county official Karen Holmes Morant calls a “network of care.”

Created and led by Morant — who is also a faith leader — and a dedicated group of clergy, it comprises an unusually wide swath of partners, including Presbyterians, Catholics, Episcopalians, Baptists, Hindus and Mormons.

Businesses offer food, and private citizens donate money. Federal, state and local governments offer funding and coordination; between April and June of 2020, the program received $1.2 million in public money.

And food is only part of the story. As needs grew during the pandemic, the program grew to meet them.

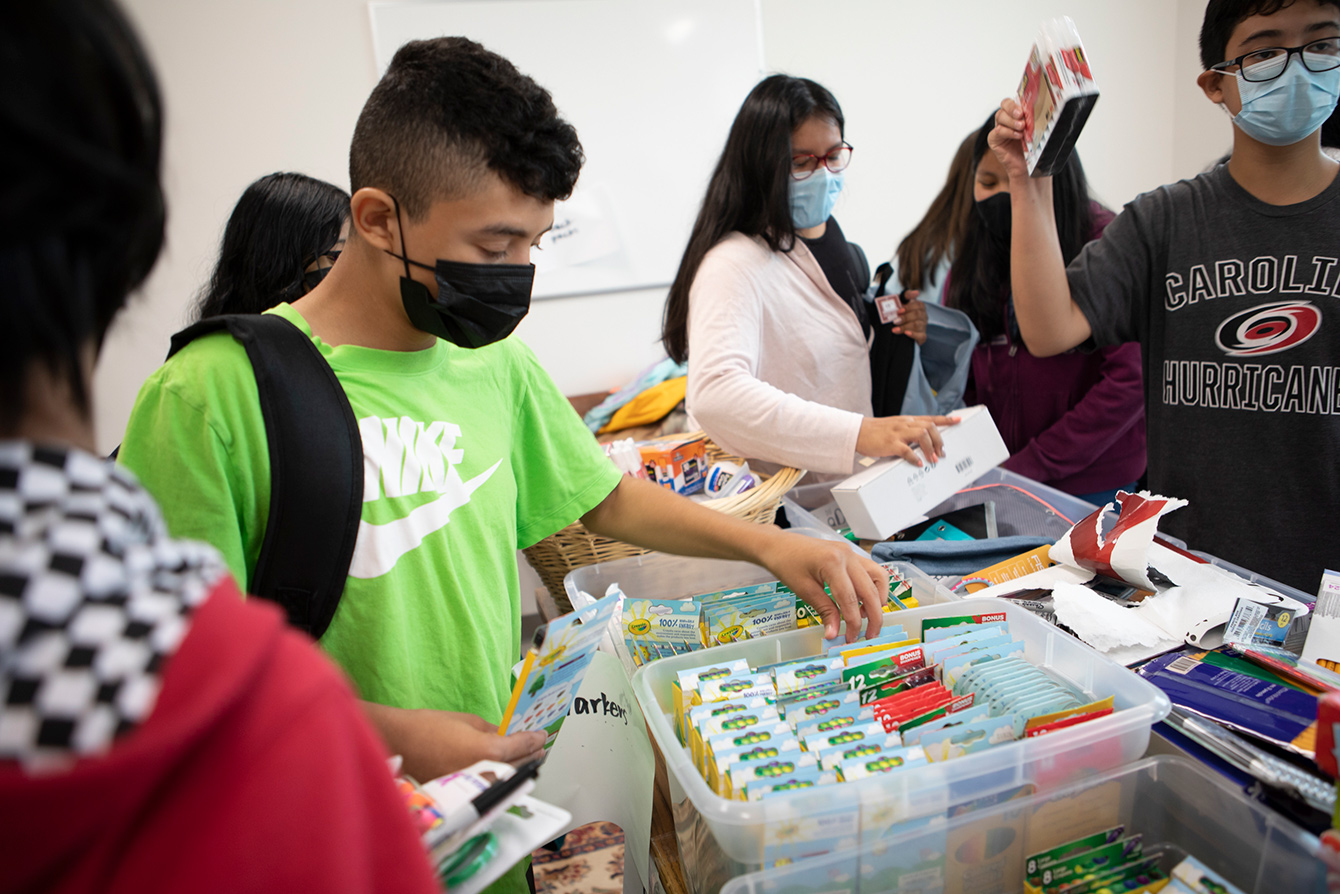

It now includes 12 sites around western Wake County where children get food, have fun, learn English and receive a variety of other services. The meal giveaway sites became places where people could access all kinds of free resources — some 79 tons of fresh produce, for example, and school supplies for 900 children.

Many of the low-income students were being sent home to take online classes yet did not have computers. Organizers obtained 30 donations of used computers, got them into working order and gave them away.

What new work might be possible if you engaged in ecumenical or interfaith partnerships? How might you work with government agencies?

The program has administered 400 COVID vaccinations and sponsored an “Ask the Doctor” day to combat misinformation and answer questions about the virus.

“I knew we had a big-hearted congregation, and all these congregations working together — who doesn’t want to help children, right?” Workman said. “It delights me, but it doesn’t surprise me. … We’ve always said God will provide, and we really and truly go with that.”

Pockets of poverty in a wealthy community

The group’s readiness for a pandemic is even more of an accomplishment considering that the initiative was willed into existence from the ground up, through faith, determination and the buy-in of key leaders.

Workman remembers exactly what she said when she stood up in front of her church in 2015 to call for volunteers for a mission that, at the time, had somewhat blurry outlines.

“Well, Jesus has told us to love our neighbors, and it’s about time we meet them,” Workman told congregants at Kirk of Kildaire.

Her goal was to put into action Jesus’ second greatest commandment — to love your neighbor as yourself (Matthew 22:39; Mark 12:31) — but it was not going to be a simple task. Kirk of Kildaire, a 1,100-member church established in 1977, was more than 90% white and largely professional.

It’s located in the home county of Raleigh, the North Carolina capital. Wake is the second-most affluent county in the state, and Wake’s western region the most affluent of the county.

According to U.S. Census figures, Cary has a median household income of about $105,000, but 4.8% of its residents live in poverty — a fair number of people in a town of 170,000.

The towns in western Wake — including Cary, Morrisville and Apex — are bedroom communities for Research Triangle Park, a 7,000-acre area outside Raleigh that is a haven for high-tech and cutting-edge companies such as GlaxoSmithKline, IBM and Lenovo.

A drive through these towns might elicit oohs and aahs at nice houses; it’s easy to overlook that they have people living in poverty as well. But Workman was among those who were determined not to overlook it.

The neighbors to whom Workman wanted to show a little love were residents in an enclave of apartment buildings about a quarter-mile from the church, occupied mostly by Latino immigrants.

Church members had long been providing tutoring services for those residents, she said, but not much else.

Workman and her fellow members of Kirk of Kildaire joined with Greenwood Forest Baptist Church to launch an effort — dubbed the Summer Program — in which they would provide neighborhood kids with food and maybe help them with English.

They spread the word, put flyers on windshields and readied the church’s fellowship hall for children.

“The very first day, no one showed up,” Workman said. “So Patty and I got in the van and drove around the neighborhood,” she said, referring to Patty Snow, the church’s neighborhood ministry director, who speaks Spanish.

“We got about 12 kids. By end of summer, we had about 100 kids. Moms got on the bus, too, and said, ‘Will you teach us English?’”

How could your church leverage available data to be a better community partner?

‘Having an impact on people’s lives’

The program has helped people like Getsemani Soto, a 17-year-old Cary High School student. For her, the experience was about much more than food.

“I got to meet a million people,” she said. “Yes, this is in my neighborhood, but … It’s a good time to bond, especially if you don’t have a lot to do over the summer.”

The most valuable part for Soto was the Career Project, in which students did research about careers or college.

“It helped guide me to have an idea about what I want to do, potentially,” she said. Soto, who was born in Mexico and came to the United States at age 1, wants to be a child care worker; there will be a big demand for those workers in the future, she said.

Elias Soto, her 14-year-old brother, chose to do the College Project. It helped him clarify his thinking about where he wants to go to college: the University of North Carolina Wilmington.

“I know more about the school because I’ve been wanting to go there for a while now, so it just helped me plan in my mind,” he said.

Their mother also improved her English, the siblings said.

Brian Cruz, a sophomore at the University of North Carolina Greensboro, spent the summer working on the College Project and assisting with food distribution.

“It’s my first time doing this kind of job, so it’s pretty cool,” Cruz said. “This is the only job I’ve had where I’ve been able to have an impact on people. Most of the jobs have been sort of menial, like working at a store — clock in and go home. But [here] you’re actually having an impact on people’s lives.”

Cruz was born in the United States, but his parents are from Mexico and he speaks Spanish. He said he can relate to program participants from other countries.

“I’m first-generation too,” he said. “I can more or less understand what they’re going through.”

‘What can we do to change this?’

What members of Kirk of Kildaire and Greenwood Forest Baptist didn’t know when they started their modest summer program was that someone else also was seeking to address needs in this apparently wealthy community.

Morant is director of Wake County’s Western Health & Human Services Center. She is also associate minister of Pleasant Grove Church in Cary. Both hats fit comfortably on her head.

Morant has religious training (a master of divinity degree from Campbell University), as well as training in both business and leadership and change management (with degrees from Johns Hopkins and Pfeiffer universities).

Her goals can sound preachy — “Get the church out of the congregation and into the community” — but her approach is wonkish: “We use data to drive us and look at what is relevant for this region. ... We like to drill down that data and overlay it on the areas on the region of the county that we serve.”

The Rev. Mycal X. Brickhouse, the senior pastor of Cary First Christian Church, met Morant as her vision for a collaborative network was beginning to take shape.

“Karen was a visionary, because she saw the need for the community to be a part of the change that was happening here,” he said.

“She really advocated for faith leaders to operate in the kingdom of God, to operate in this model where denominational affiliation just didn’t matter, where our theological differences didn’t divide us from doing good.”

A study Morant coordinated found that 90% of the residents in that area who were eligible for social services such as WIC and Medicaid were traveling to Raleigh to get them. The study made clear what many local officials and faith leaders already knew, Morant said: people in western Wake needed help.

“Apex, Cary and Morrisville happen to be the wealthiest region in Wake County. … The thought was that government services weren’t needed,” Morant said. “[But] there is hidden poverty in this region.”

Morant was convinced that the government alone did not have the ability to help all of the western Wake families that needed it. The need for a broader approach became clearer when she learned that in the 2016-17 school year, $8 million in state funding for food for low-income children had gone unspent.

She went about creating a “community conversation” among faith leaders, municipal officials and county officials designed to answer the question, “What can we do to change this?”

“I’m looking for transformational leaders in the business sector, the government sector and the church, and also in the community, so we can work alongside each other to redevelop the community,” she said. “Our nonprofits and our churches have always been a great resource in our community.”

This effort swept up a number of churches, including Kirk of Kildaire, and led to the creation of the Western Regional Food Security Action Group, of which Workman is now president. Its goal is to play an active role in the community’s “network of care.”

Morant reached out early to Brickhouse, who shared her strong belief that poverty in Cary was not being adequately addressed and churches had a role to play.

What are some resources — not necessarily money — that your church could bring to a community collaboration program?

“We connected on thinking about how we could work together and bring this congregation in on this project for the welfare of Cary,” said Brickhouse, who is also director of alumni relations at Duke Divinity School.

Brickhouse’s church is one of the initiative’s food distribution sites, serving clients who are African American, white and Asian.

The town, well known for design rules that promote beautification and conformity, requires extensive landscaping that hides eyesores and also obscures poverty, Brickhouse said. “That may not be the intent, but that’s the outcome.”

“The [low-income] neighborhoods are largely hidden behind trees, behind large shrubs and those types of things,” he said.

Brickhouse called the pandemic mobilization something close to a “biblical miracle.”

But the help the initiative provides can be important even on a smaller scale, said Patty Snow, the neighborhood ministry director who’d hopped in the van on the first day of the Summer Program to look for kids.

In an era of COVID, parents have been particularly concerned about official-looking letters, she said. Sometimes, participants take photos of such letters and text them to her, saying, “This looks important” and asking her to translate, Snow said.

“At least now they feel that somebody cares,” she said. “That’s how we want for them to feel — that there’s somebody who has their back in difficult situations.”

Alex Schwindt contributed to this story.

How might you design a ministry so that it meets an immediate need but also lowers ongoing barriers to equity?

Questions to consider

- The Rev. Stephanie Workman said, “When the pandemic hit, we were ready.” Is your congregation ready as the pandemic continues? Could you retool or expand existing ministries to become ready?

- What new work might be possible if you engaged in ecumenical or interfaith partnerships? How might you work with government agencies?

- How could your church leverage available data to be a better community partner?

- What are some resources — not necessarily money — that your church could bring to a community collaboration program?

- How might you design a ministry so that it meets an immediate need but also lowers ongoing barriers to equity?