Ryan Burge and Tony Jones know the religious landscape in America as pastors and as researchers. They are two of the nation’s leading experts on the declining role of the church and the rising significance of 100 million Americans — broadly categorized as the Nones — who seem to have left organized religion entirely.

Or have they?

Burge and Jones have recently launched The Nones Project, an online resource of their ongoing work as part of the Making Meaning in a Post-Religious America Project, funded by the John Templeton Foundation.

In August, they spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Aleta Payne about their findings. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: The Nones are often thought of as a single group, but you’ve found they’re not. We have the Nones in Name Only (NiNOs), Spiritual but Not Religious, the Dones and the Zealous Atheists. What’s important to know about them?

Ryan Burge: The NiNOs are so interesting because they’re actually probably religious. They just don’t want to use the language of religion to describe themselves. They pray as much as Protestants and Catholics do. The vast majority believe in God, believe in the afterlife. We have these very black-and-white categories in social science. Either you’re this or you’re that. The reality is this is blurry. A lot of these people, on the right day, if you ask them their religious affiliation, might actually say they’re Christian or Catholic or Protestant or something. They’re just reluctant to do that.

In some ways the Nones actually probably aren’t as big as we think. That’s one of the big findings: We’ve got to think of this as more of a gradient than discrete boxes. People move up and down that gradient over their lifetime. That’s one of the most important findings, especially with the NiNOs.

Tony Jones: We did the largest survey ever conducted of non-religious Americans. In a survey, people are necessarily self-reporting. Another learning that Ryan has written about recently is that the SBNRs (Spiritual but Not Religious) are not very spiritual. They aim to be spiritual, but when we drill down about what they actually do on a daily or weekly or monthly basis — Do you pray? Do you pull tarot cards? Do you take a walk around the lake and commune with nature deliberately? — They really don’t.

We’re not superimposing a definition of spirituality on them or even of non-religious. To Ryan’s point that a lot of NiNOs claim to be Nones, they say in a survey, “I do not affiliate with any organized religion.” Drill down and look at their behavior: They go to church, they pray, they’re getting married in churches. They seem pretty religious, but they say, “Oh, no, no, no, I’m not.”

That’s why I think mainline clergy are so confused by this. I would hope that our results can bring a lot more nuance to the conversation about the Nones. They’re not a monolithic group.

RB: That’s a key point. We want people to self-identify. There is no accepted definition of these terms. My approach to all this has always been, “If you say you’re spiritual, then you’re spiritual. If you say you’re not, you’re not. If you say you’re not religious, even though you go to church every week, you’re not religious.”

I’m not going to call you what you don’t call yourself. Self-identification is the simplest, most defensible way to go about this kind of work. I think we can learn a lot more by just listening to people tell us what they are instead of us trying to be paternalistic — like, “Oh, no, you actually are spiritual; you just don’t know it.”

TJ: One of the things that’s been fun about the data and rolling it out now in year three is we’re doing a lot of myth busting. One of these myths in the zeitgeist or in the ether right now is, “Oh my gosh, so many of these Nones are evangelicals. They grew up in fundamentalist churches. Now they’re pissed off and they’ve left and they’re angry atheists.” That’s not at all what we found about the Dones and the Zealous Atheists.

RB: The reality is that loud voices don’t represent most voices — very few Nones are exvangelicals. And the share of non-religious people who said they would ever identify as evangelical in their entire lives is 15%, which means 85% of Nones are not exvangelicals. It’s obviously more than zero, but it doesn’t need to take up all this mental space that we’ve created for it.

I looked at people who said, “I grew up in a very religious household. Both my parents went to church once a week.” Just 13% of Nones grew up in a highly religious Christian household. It should not take up as much time as we’re giving it in the discourse.

Most Nones have been Nones their entire lives or been marginally religious and now are not religious. I think that’s a very important point that we can’t make enough: The number of people who go from one side of the spectrum to the other is incredibly low, whether it be atheist to evangelical or the opposite direction. The problem is we’re drawn to those dramatic stories of radical conversion, but in reality that does not represent the average person. In this project, our job is to represent the average experience, not the exceptional experience.

F&L: Everyone wants an answer, a fix, “Here’s the thing to do and the numbers will go up.” What I hear you saying is the quick fix is not the quick fix.

RB: There is no quick fix today. Tony and I are very clear about this. We’re not doing this work to say, “How can Christian people bring Nones into religion?” This is not an evangelical project. Our goal is not to write a guide to get people back in church.

Our job is to describe the world as accurately and as objectively as we can. Our primary aim is to be scientists — to be academics and not evangelicals. It’s just generic, neutral academics in this space.

F&L: As scholars who both have pastored, what in this research surprises you?

TJ: I think the NiNOs surprised me the most. Like Ryan said, they look very religious in their behaviors. They seem to be predisposed to religious practice. One thing I’d say to pastors is that Nones are not monolithic. If you’re looking to invite non-religious younger Americans into your congregation, figure out who they are. Don’t think of them as one huge monolithic group of 100 million people.

RB: The consistent finding is the Nones don’t hate religion. The majority of them are sort of warmish for the idea of religion. They’re just not religious. Pastors want to create this cosmic battle. Evangelicals are fighting the godless atheists and atheists are like, “We don’t hate you, man. Stop trying to make us into what we’re not.”

At the same time, I would say to atheists, stop making all evangelicals into fascist, racist, xenophobic people, because they’re not. I have a book coming out in January that makes this point. We’ve got to stop listening to the 5% on each side and focus on the 90% in the middle, because we’re not as polarized as we think we are. Most Americans are practical, they’re reasonable, they’re willing to compromise and see the other side.

The bomb throwers are not the median person. That’s what’s great about survey research. We can hold up a sign that says, “I know that person said something absolutely crazy, but they represent 5% of America, so you can probably safely disregard them. It’s OK.”

I think that evangelicals need to get it out of their minds that the Nones hate religion. They don’t. I ran a piece in my newsletter from Pew data, and actually 60% of Nones believe the church is building community. Now, they also think they care too much about politics, and there are too many rules. But you just do not get the sense from the data that there’s this huge well of anger and hatred toward religion in America.

For most, it’s just a malaise — it’s just, “I don’t care either way.” Which, if you’re a Christian, I think is very hopeful to you. You’re not trying to take them from “I hate you” to “I love you.” You’re trying to take them from “I don’t care about you” to “I can deal with you.” That’s a much easier lift.

TJ: Frankly, that’s an indictment of mainline church. So many of our mainline churches are not giving those Nones any reason to try a church because they’re just cranking out the same liturgy every week. They’ve got the same people running the church who’ve always run it the same way. I’m not saying that as an indictment of the people who are doing their best on a daily basis. But, in general, the mainline church in America, in my estimation, has really dropped the ball. Innovate and try to stay culturally relevant so that these non-religious Americans might say, “I’ll give it a try. I’ve heard there’s some great stuff happening over there.”

F&L: There’s something that being a part of a regularly meeting faith community fills in us. What’s filling that for this segment of humanity?

RB: We have a whole battery of questions about life purpose, meaning, friendship — all these questions to try to figure that out. We were told growing up, “If you don’t have God, your life’s going to be bad. You’re going to struggle and you’re going to suffer.”

And you know what the data says? Not really. There’s a small gap. It’s definitely not like a five-alarm fire. For a group like the Dones, they are doing fine on mental health questions, at least self-reported.

The argument that churches make, “You have a God-shaped hole, and we can fill the God-shaped hole” — Nones reject everything about that, and they’re suffering no illness from that. The data should put a lot of us in a theological crisis because the basis of what we were taught “No Jesus, no peace. Know Jesus, know peace.” The data says there are a lot of people who don’t know Jesus and are living fairly peaceful lives. What does that say about Christianity?

Maybe this research at the end of the day tries to answer the question, “Is everyone open to receiving the message of Jesus Christ?” And the answer in this data is no, they’re not.

TJ: Probably the most incisive work that’s been done on this is by Charles Taylor. It is just very hard in a disenchanted world for a religious system to say to people, “This is really an enchanted world. We really do hold the keys to the kingdom of Heaven.” People kind of roll their eyes at that when science gives them the framework of understanding everything that happens. That’s a huge challenge.

As a theologian and a pastor, I was kind of hoping that our research would uncover that a lot of Nones are still seeking transcendence. I am a pastor who now spends as much time as possible outside in the woods seeking transcendence. But most Nones aren’t really seeking transcendence, and they don’t miss it. They don’t miss whatever it was that church offered.

Back 500 years ago, the church said, “We have the keys to the kingdom, we have the keys to eternal life. If you don’t come and get your kids baptized here and drop money in the plate, you might spend eternity burning in conscious torment.” People just don’t believe that anymore, which means that on a purely secular or a market-driven basis, what is the church offering to people?

F&L: What haven’t you gotten to talk about that you’d like to?

RB: People don’t think about religion like we think about religion. Tony and I spend literally our lives, our vocation and even our hobbies in some ways are wrapped around this idea. But guess what? The average American hardly thinks about religion at all.

When people make decisions, they don’t make them consciously or purposefully sometimes. Why do they leave church? For us, it’s got to be some sort of big theological debate or political debate or societal change. And for them, it might not be any of those things. Even if you try to ask them multiple questions about why they left, are you trying to put smoke in a box? Trying to categorize something that in some ways is ineffable?

It’s just bigger than that or smaller than that, too, where there is no reason for it. That’s what we struggle with. We want to have discrete reasons why people left church. I think for most people it’s not a conscious thing at all. It was just, “I drifted away,” or “I was never that attached to begin with. And my life is not better or worse.” That framework is something I have to constantly remind myself of.

Am I overprescribing the Nones? Am I trying too hard to give meaning to something that doesn’t have any inherent causal mechanism? I don’t have an answer for that, but I do know people, especially pastors, want to believe that there are causal mechanisms. Our job is to try to put smoke in a box, to try to make sense of that in some way, because a little bit of knowledge is better than no knowledge in this space. To use the Pauline phrase, “looking through a glass dimly lit” — our job is to turn the light up 5% knowing that we’ll never get to 100%.

TJ: For those of us who went into ministry, it was like, “Oh, I have a special calling from the transcendent creator of the universe to do this job. I’m special. What we do in ministry is different.”

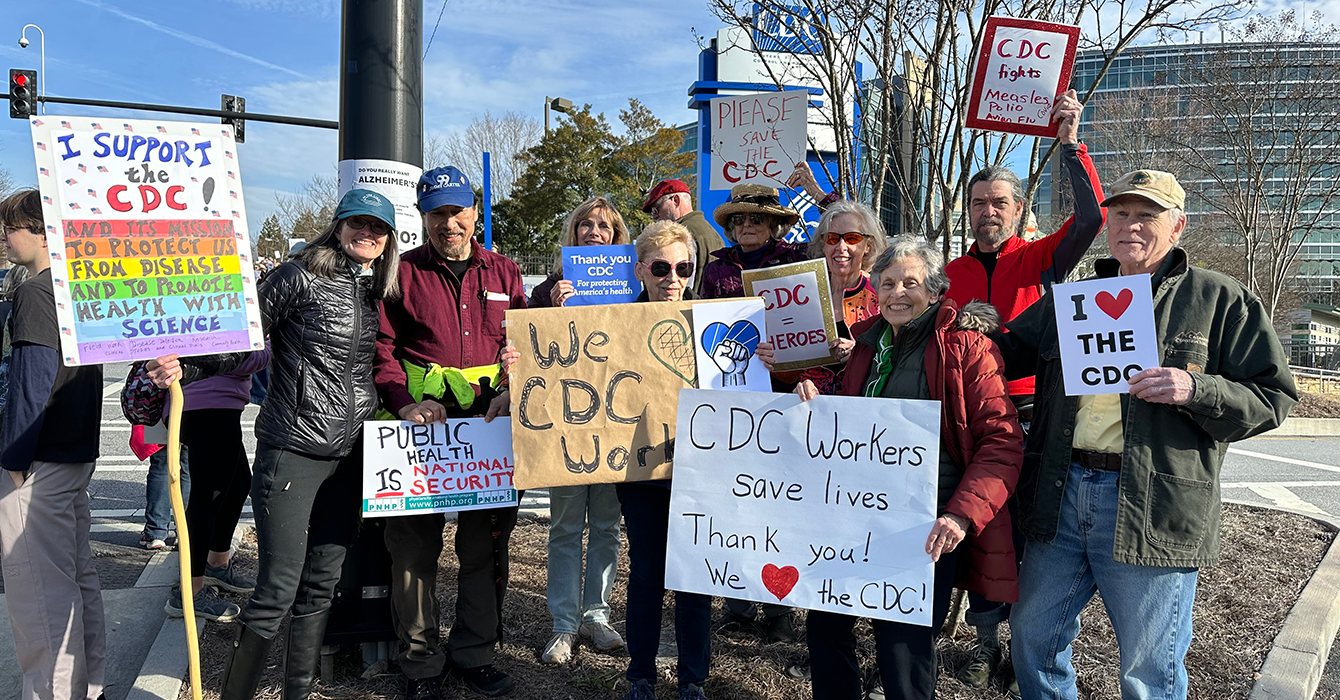

On a social science level, it’s not different. The church has struggled in the same way that the Lions Club and Rotary have struggled, and every other voluntary association.

I saw a statistic about how American parents spend their time if their kids are in traveling sports. They don’t have time for church or Rotary or the Chamber of Commerce or running for the school board or the Knights of Columbus or being a Shriner or a Mason. There’s no time. They worship their children. Their church is bleachers at a soccer game or a baseball game.

There are massive shifts taking place in American life, and the church isn’t a unicorn. The church is part of that shift. It’s hard for church people, because we think the church is special. The church is different from Rotary, of course it is. But in these massive demographic shifts, the church is just another voluntary organization in which Americans are spending less and less time.

RB: The things that animate membership and time in those voluntary social organizations are the things that animate membership and time in church.

This is the hardest part about my work. People are like, “My church is growing because we have the Holy Spirit.” And I’m like, “No, your church is growing in a rapidly growing community.”

I think that’s where pastors have a hard time with what we say in this context, because they want to believe it’s all supernatural, and we can’t believe any of it is supernatural.