In early fall 2021, nearly all of the pastors surveyed by Lifeway Research said their congregations were meeting in person again, but 87% said their attendance levels were less than half of pre-COVID numbers

The phenomenon has spread beyond congregations, too: One campus minister told me in frustration that his students were always a minority on campus but that COVID restrictions had made it even easier for them to step over the threshold into the world of the religiously unaffiliated, or Nones.

The rise of the Nones was already one of the most significant developments in American religion before the pandemic began. Once churches closed their doors, even the most devoted churchgoers were forced to develop new habits.

As Robert Putnam and David Campbell documented in “American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us,” little more than a decade ago, increasingly vocal divides breaking along political and religious lines already had been turning young people away from religion. This further weakened the appeal of the church for some believers and for most Nones.

What if, between those lingering frustrations and these new COVID-required behaviors, more of what I’ll call “Somes” – those who still identify with a religious tradition – join the Nones?

What if we all become Nones?

It has never been clearer that the church must engage with the Nones in order to survive. This is true in part because that group now contains more and more of the church’s own daughters and sons.

In many ways, what the pandemic is doing is not simply generating new behaviors of non-attendance but also revealing what is already there. I suspect that many Somes are not too different from Nones on the spectrum of behaviors and beliefs, even if they stand on different sides of the church door.

Any strategy of engagement and revitalization needs to begin with trying to answer the questions: What do the Nones need? And how can we truly hear them?

According to the latest Pew Research Center report, the Nones group has grown from 5% of the population in 1975 to almost 30%. If we are to give them a place of spiritual connection and learn from them, we may need to think less about what we stand for (sometimes defensively!) and more about what we stand in.

Are we standing in agape-love – not just for those outside the threshold of the church but also for those already inside it? Are we a community of love, where wounds are bound and needs are met in concrete, tangible ways? Are we a community that gives dignity to difference?

And, even more importantly, can we ask these questions while being rooted and grounded in love (Ephesians 3:17 NRSV) rather than while standing in the anxiety of institutional survival?

We also need to consider whom we are standing with.

We live in a traumatized culture. The pandemic has left few people untouched and has further opened our eyes to the preexisting trauma systemically embedded in race and class distinctions. Unless the church can find a way to stand with those who are traumatized, many will continue to view the church as complicit in the trauma.

Just as God revealed his unspeakable name and holy purpose when he heard the cry of the people (Exodus 3:7ff) and just as the God of the resurrection aligned with the crucified one and not the dominant powers of society, how can the church create spaces where it hears and stands with those who are traumatized – whether the Nones, the disengaged Somes or those society rejects?

In those creative spaces, we are called to listen deeply and collaboratively until we find ourselves standing in a “with-ness” that overcomes the delusion of our differences and the dominant defenses we use to avoid suffering. In that place of “with-ness,” the “with-us” God always chooses to reveal and raise up what is next.

Finally, we must reimagine the threshold we are standing on.

For too long the church door has marked who is in and who is out: Nones on one side of the threshold and Somes on the other. Now, we are being invited to stand together on the same threshold: the threshold of possibility.

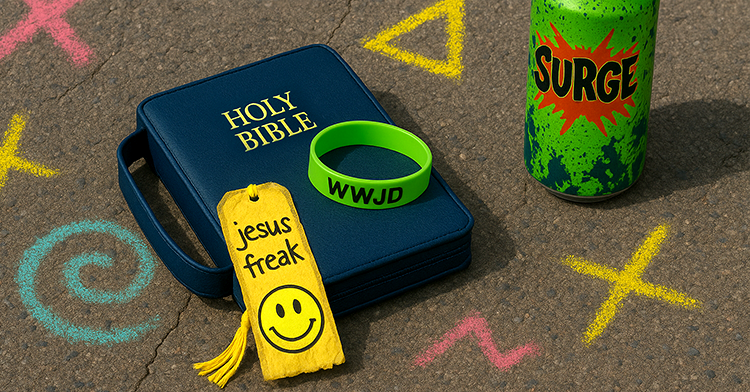

This threshold can occur anywhere. When Elizabeth Drescher asked more than 1,000 people about the spiritually meaningful practices in their lives, Nones ranked spending time with family, friends or pets or preparing food as their top four. Drescher calls these the Four F’s of Contemporary Spirituality: Family, Fido, Friends and Food.

Prayer came in at No. 5 on the list, but things like attending worship or Bible study ranked at the bottom. Spirituality in everyday life was more authentic for them. Interestingly, the Somes who participated in this survey ranked meaningful spiritual practices in the same order!

Perhaps the threshold on which we are called to stand together is found in the places of everyday authentic spirituality. And, perhaps, like Jacob we will find that “the Lord is in this place – and I did not know it” (Genesis 28:16 NRSV).

If this is true, then our task as leaders is to align with the Nones in the ordinary. We must take a position, like Jacob, of humility and not-knowing. This opens us to the possibility that the threshold on which we stand is none other than the “gate of heaven” (Genesis 28:17 NRSV).

It is here that we, as 15th century German philosopher Nicholas of Cusa said, come into a higher awareness of God as posse ipsum – possibility itself.