The capital city that Virginia shared with the Confederacy lay in ruins when a half dozen members of the Sisters of the Visitation left their Baltimore home in 1866 to establish a monastery on the crest of Richmond’s highest hill. Recruited by the Catholic Diocese of Richmond, the sisters of Monte Maria were charged with praying for the healing of the broken city and its beleaguered residents, a task they undertook daily for more than a century.

When the sisters decided to sell the property after 120 years, developers salivated at the prospects. The 2-acre plot, tucked into the historic Church Hill neighborhood, offers a 270-degree view of the city below, with the falls of the James River visible to the west.

The Rev. Benjamin Campbell, an Episcopal priest and Church Hill resident, had heard about the pending sale, but it wasn’t exactly top of mind for him. He’d spent years raising money for social justice projects and running nonprofits aimed at dismantling Richmond’s racist legacy. That was no easy task, and along the way, he’d struggled with alcoholism, lost a marriage and entered recovery.

Feeling defeated and overwhelmed, Campbell says, he was strolling along Grace Street past the hot property when he felt that the Lord said something to him — “which is not something I normally feel,” he said with a chuckle. “And what I understood him to say is, ‘This is supposed to be an ecumenical Christian residential community praying for the city.’”

Perhaps that was the property’s destiny, but Campbell felt certain he wasn’t the one to lead the charge.

“My comment to what I understood was being said to me was, ‘I’ve done this. I’ve raised money constantly. I am exhausted … and I cannot do it again,’” he said. “What came back to me was, ‘Yeah, and on the third day, I rose again,’ which was a really big card to play.”

Soon, Campbell was urging congregations and nonprofits to help preserve the property as a place of prayer and a home for racial reconciliation efforts. He found broad cross-denominational support, and after a developer’s bid for the property fell through, a nonprofit established by Campbell and other church leaders purchased the land in 1987 to establish Richmond Hill.

Almost four decades later, it remains an ecumenical Christian residential community and spiritual retreat center, where staff, some of whom live on-premises, and volunteers and visitors continue the sisters’ tradition of praying daily for the Richmond metropolitan area and everyone in it. Prayer, hospitality, racial reconciliation and spiritual development continue to serve as the facility’s four pillars and the inspiration for all of its programming.

Do you feel exhausted? What would it take for you to “rise again”?

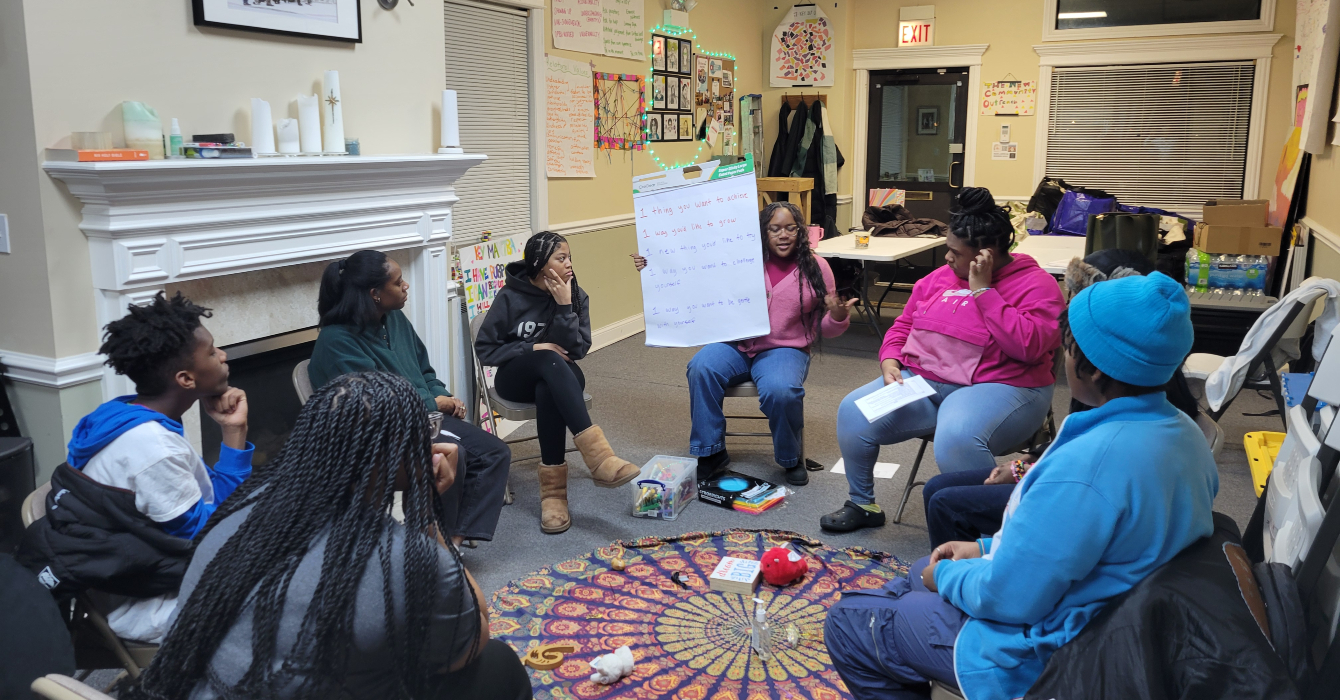

In addition to prayer three times daily, Richmond Hill hosts community meals as well as group and individual retreats, coordinates mentoring and leadership development for students at nearby city schools, and offers a two-year program for those called to the ministry of spiritual direction. Its commitment to racial reconciliation spawned the Koinonia School of Race & Justice, where participants identify issues related to systemic racism in Richmond, along with strategies for countering them.

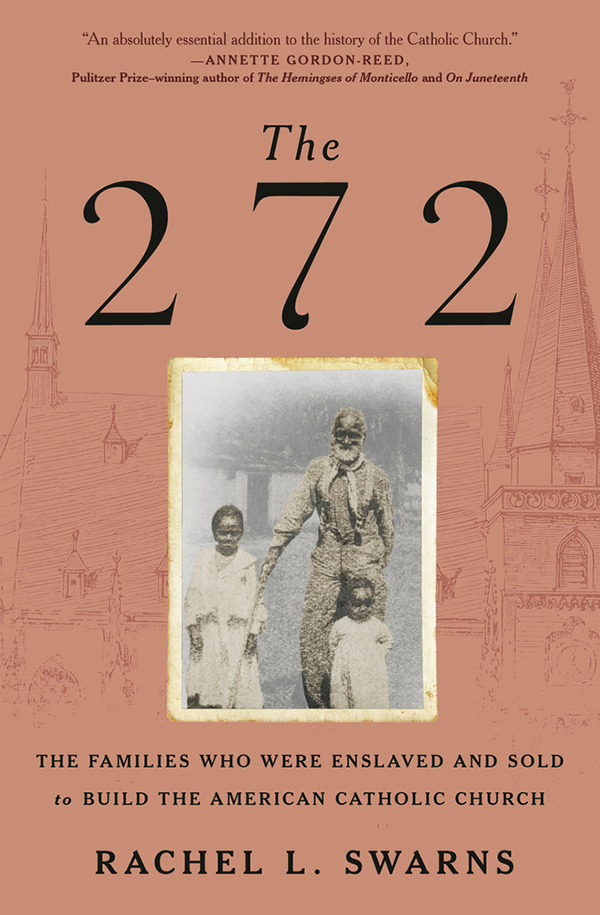

That commitment has also resulted in self-reflection and truth telling. It’s estimated that some 200 individuals lived in bondage on the property during the generations before the Civil War, and the Judy Project, named for one of them, seeks to uncover their identities, locate their descendants and educate the public about the institution of urban slavery.

In 2020, archaeologists determined that a structure on the property had once been a dwelling for enslaved people. Pressed into the northeast corner of Richmond Hill’s garden, the building had been used as a tool shed by the sisters, who had hailed from a slaveholding order. The nonprofit has publicly acknowledged the oversight, and efforts are underway to preserve the dwelling as a place of healing and contemplation.

The phrase “thoughts and prayers” can feel passive and disengaged. Richmond Hill residents try to pray and act. What form might that take for your organization?

“I think part of our problem in this country in terms of racial healing is not wanting to acknowledge the truth — and the dwelling represents so much of that truth,” said the Rev. Lorae D. Ponder, the acting pastoral director at Richmond Hill and associate minister at a nearby Baptist church. “We have to reconcile that while the church was praying, there were enslaved people. We don’t reconcile that by denying it happened or not addressing it. This is a place where the truth dwells.”

The facility is in a time of transition, with Ponder and two other staff members in interim leadership roles after some of Richmond Hill’s lead pastors were called recently to serve elsewhere. In the coming months, a search committee will be convened for the purpose of calling the next pastoral director. But the facility’s staff, volunteers and governing council aren’t wasting this season. Focused on a relatively new three-year strategic plan, they’re trying to lift up their unique programming, steward the land and aging infrastructure in thoughtful ways, and equitably sustain the people who live and gather there.

“Hospitality is really the heart and soul of it,” Ponder said. “As we practice hospitality and pour that love into individuals, that love begins to transform those individuals, and they take that love and transform the community.”

A place of hope, hospitality and prayer

The daily cycle of prayer at Richmond Hill has been unbroken since the Sisters of the Visitation’s arrival, but there’s anecdotal evidence that Native Americans used the hilltop as a place of prayer for millennia before Europeans claimed the land in the early 1700s.

Now, each day at 7 a.m., noon and 5:30 p.m., a bell summons everyone there to the Chapel of the Sacred Heart to offer prayers that change daily. On a recent Thursday afternoon, roughly two dozen visitors, staff and residents paused for the pre-lunch service. Their prayers included the citizens and government officials of five communities in the Richmond metropolitan area before also asking that the banking and finance industries make sustainable decisions for the region.

They prayed that God bring justice to the correctional system and bless its employees, inmates and their families; that God look after public servants, the underemployed and the unemployed; that gardeners and their plants be nourished; that educational institutions flourish; and that the ministries of Richmond Hill and those gathered there be protected and nurtured.

“The rhythm of prayer, three times a day, what it really focuses on is intercession for the metropolitan city. You’re not in a theological battle. You’re praying the prayer we all have,” Campbell said. “I love what God is doing here. It’s a place of hope and hospitality and genuine prayer — and genuine prayer is not sectarian.”

The distinctive clang of a cowbell announces lunch in the refectory, where a communal meal is followed by “the ministry of dishwashing.” Richmond Hill’s apartments do not have kitchens, so the residents — currently including six staff members, two spouses and four children — eat all their meals together. The community is invited to join worship and meals on Tuesday evenings and Thursday afternoons. Richmond Hill favors “the original ‘face time,’” according to the Rev. Thomas Baynham, so cellphone use during meals is strongly discouraged.

Baynham joined the center’s staff and residential community in June after a monthslong discernment process that led him from a United Church of Christ congregation in Missouri back to his hometown of Richmond. He serves as pastor for hospitality and welcome and is also an acting assistant pastoral director.

The rhythm of the place takes some getting used to, Baynham said, but the intentional community offers a “tremendous amount of forgiveness” for new arrivals, along with daily opportunities to be authentic and model the change they hope to see in the world. For Baynham, that means making sure each visitor gets exactly what they need, from a vegetarian meal to a parking spot close to the building.

“Everything that goes on at Richmond Hill intersects at hospitality,” he said, shortly after helping a large contingent from a Christian missions organization settle into a meeting room. “I don’t want to use the word ‘magical,’ but I would say spiritual. There’s very much a sense of peace about the place. And you get to enjoy the peace of it while also knowing you have to put up with the chaos of it.”

The Rev. Kelsey Hawisher-Faul and her husband, Peter, both Presbyterian ministers, had spent years thinking about living in an intentional community before moving to Richmond Hill about two and a half years ago with their infant daughter. Hawisher-Faul said the mutual discernment process for potential residents includes interviews with Richmond Hill’s leadership, staff, volunteers and residents, a psychological assessment, and an in-person visit to make sure it feels right to all involved.

Residents generally commit to staying for two to five years, also going through an annual rediscernment process to make sure they’re still called to be there. Staff who live at Richmond Hill receive food, health care and contributions to their retirement, in addition to housing, but the stipend is small and may prove financially challenging for some, said Hawisher-Faul, who is Richmond Hill’s development coordinator and residential moderator.

In what ways can you balance peace and chaos?

Living in a place like Richmond Hill requires an ability to self-reflect and an openness to learning, she said. It also means having face-to-face conversations rather than sending emotionally charged emails, and practicing self-care so you can be a healing presence for others.

Hawisher-Faul, an introvert, said the demands of such residential life require her to manage sensory overload. “The conversations are so wonderful, and the opportunities for connection are so abundant. Being at Richmond Hill, the spiritual life is really close to the surface. That’s both a gift, and it can be really intense.”

‘Trying to heal what’s been broken’

Like many of the visitors to Richmond Hill, Hawisher-Faul said she often turns to the garden for peace, practicing tai chi and mindfulness meditation surrounded by birds, bees, butterflies and other critters. Since June 2021, co-gardeners Beth Nelson and Allison Hurst have been “rewilding” the garden, removing some of the stately but invasive plants and replacing them with native flora that can better support the ecosystem.

A family of hawks has made its home in the garden, and nearby beehives yielded 70 pounds of honey this year, said Hurst. Richmond Hill largely avoids using synthetic fertilizer or other chemicals, and a National Fish and Wildlife grant is supporting the development of a stormwater runoff plan to route water into “spaces where it can be life-giving, rather than destructive,” Hurst said.

“If you’re going to do the work of reconciliation and be contrite, then we need to counter the damage to the land,” she said. “We’re trying to heal what’s been broken, and we want to invite people into a place of wonder and whimsy, a place of devotion.”

Just over the brick perimeter wall, a holdover from when the sisters there were cloistered, children at a nearby elementary school enjoy recess, ambulances wail, and traffic on the interstate whizzes past.

“There’s a serenity in the garden even in the midst of the hustle and bustle of the city around you. And that’s the draw for folks,” said the Rev. Sheryl Johnson, also an acting assistant pastoral director. “In a way, it models what they’re trying to do in their own life with spirituality — to quiet yourself in the middle of chaos. This place is a testament to that possibility.”

The peace of the garden stands in stark contrast to the lives of the enslaved individuals who once toiled on the property and lived there, said Lauranett Lee, Richmond Hill’s director of race and social justice. From the hilltop, they would have had a clear view of the markets along the James River where an estimated 350,000 men, women and children were jailed, bought and sold, she said.

At least one of them, Judy, had an unobstructed view of Union troops entering the Confederate capital in spring 1865. For four generations, she’d served the Wilkins family, which lived on the property before the sisters. In a late-in-life letter to relatives, one of the Wilkins children recalled Judy carrying her to a high porch, pointing at the troops in the distance and whispering, “Always remember that you saw history in the making when you were 4 years old.”

Richmond Hill’s garden and the dwelling, which has been stabilized in anticipation of a rehabilitation project, serve as a “classroom without walls,” Lee said.

“You would never think on this property there’s a dwelling where enslaved people lived, because it’s so bucolic. The horrors of slavery — how could that happen here?” she said. “We’re going to make sure it’s not prettied up but used as a place for healing prayer, lamentation and reflection.”

How could you unearth the stories of those harmed by past actions? Are they connected to harms that continue to this day?

‘God is holding this place’

Like the city that surrounds it, Richmond Hill has faced its share of challenges. The oldest building dates back more than 200 years; caring for the aging structures and grounds is an ongoing task. During the height of the pandemic, Richmond Hill closed to retreatants. Several months after its 2022 reopening, pipes froze and burst on Christmas Day. The resulting flood caused extensive damage to several recently renovated floors across two buildings, forcing an eight-month closure for repairs.

Remarkably, the chapel and refectory were spared, so prayer services, Tuesday night Holy Communion and community meals continued. Donations from longtime supporters helped offset lost revenue.

While the Rev. Lindsey Franklin, the associate pastor for development, acknowledges that she’d like Richmond Hill’s finances “to be a little less fragile,” she also notes how grateful she is for the facility’s broad ecumenical support.

It takes about $1 million annually to operate Richmond Hill, and roughly half of that comes from donations. A recent 48-hour fundraising effort came in just over $47,000, shy of its $70,000 goal. But Franklin was all smiles, celebrating that 107 of the donors were new.

“It has run on a lot of faith and heart and love,” she said. “God is holding this place. There’s a magic here that’s hard to quantify.”

Franklin interned at Richmond Hill in 2017, and the Harvard Divinity graduate joined the staff in 2019. Though she’s a New England native, her grandmother grew up in Richmond. Franklin ultimately learned that her ancestors had been among the city’s first enslavers. Trying to live “a reparative life” has become a huge part of her faith journey.

“One thing I think a lot about is white people being able to look clearly at themselves and at history and not getting stuck there but more fully coming into a life of justice. This place has been an important part of that for me,” she said. “It’s both a retreat and an outward-looking mission. It’s not to escape but to connect to the city more deeply. It’s become a spiritual anchor at a time when a lot of us feel really untethered, an anchor to the city and to God.”

Finding a way to quantify the transformative experiences of those who have spent time at Richmond Hill is one of the governing council’s goals, said Council President Katie Johnson, a graduate of Richmond Hill’s RUAH School of Spiritual Guidance and a pastoral associate at a nearby Catholic church. While staff track dollars collected and seats filled, Richmond Hill’s caretakers aren’t fond of using those numbers to measure success.

“We’re not called to be successful. We’re called to be faithful,” she said, paraphrasing Mother Teresa. “We’re trying to find a way to measure the impact of people’s time at Richmond Hill. It’s important for us, as we do the work of historical discovery, reclamation and restoration, that places like Richmond Hill … hold space for repentance and healing and repair, and commit to move forward as a place of justice, a place of reform.”

Richmond Hill sits in the tension between retreat and engagement. Where do those tensions exist in your life or your organization? Is your work appropriately balanced between the two?

The positive side of Richmond Hill’s fragility, said Johnson, is that it will always need tending, which invites opportunity and participation. At least two dozen regular volunteers greet visitors at the front door, help prepare meals, operate the bookstore and the 4,000-volume library, and assist in the garden.

Part of what makes Richmond Hill such a spiritual place is that “the layers of history are so alive and concentrated” there, said Franklin. The highest hill in Richmond has borne witness to tremendous injustice: the displacement of Indigenous people, colonization and the slave trade, the Civil War followed by the Lost Cause narrative — and more recently, redlining, divisive urban renewal projects and gentrification.

If renewal, repair and reconciliation can happen there, it ought to be successful anywhere, she said.

“It doesn’t mean the rest of the country isn’t implicated,” said Franklin, “but if we can do it here, think of the transformative potential.”

Campbell, who served as Richmond Hill’s first pastoral director and is credited as one of its founders, said he still marvels at “the impossibility of the place” — that churches and other supporters were able not only to preserve it but also to sustain it as a place of prayer and spiritual healing.

“I believe God wanted it to happen. I believe God still wants it to happen,” Campbell said. “It feels like a continued blessing and a testament that God cares about the city of Richmond and its people and the redemption of the racist and oppressive history of the place and longs for the hope of overcoming the racism and abuse of the present; that God is nonsectarian; and … that justice, peace and love are in fact his intentions.”

What weaknesses in your work could be reframed as strengths?

Questions to consider

- Do you feel exhausted? What would it take for you to “rise again”?

- The phrase “thoughts and prayers” can feel passive and disengaged. Richmond Hill residents try to pray and act. What form might that take for your organization?

- In what ways can you balance peace and chaos?

- How could you unearth the stories of those harmed by past actions? Are they connected to harms that continue to this day?

- Richmond Hill sits in the tension between retreat and engagement. Where do those tensions exist in your life or your organization? Is your work appropriately balanced between the two?

- What weaknesses in your work could be reframed as strengths?