In 2016, Rachel L. Swarns wrote a story for The New York Times about a little-known aspect of Georgetown University’s history.

Strapped for money and envisioning an expansion of Catholic institutions up the Eastern Seaboard, Jesuit priests in 1838 arranged a mass sale of the enslaved people on the Catholic Church’s plantations in Maryland.

Now, emerging information about the sale — and questions about what the university and the church owed the descendants — had sparked student protests on campus. The students created the hashtag #GU272 and began by demanding that the names of the architects of the sale, two Jesuit priests who were former presidents of Georgetown, be removed from university buildings.

The university quickly agreed to change the building names, but Swarns wanted to dive deeper.

“I started looking at a story about Georgetown and its history,” she said. “And I realized, ‘Oh, wow, wait a second, I’m looking at a story about the Catholic Church and its emergence, at first in the British colonies, and then in the U.S.’”

Swarns, a longtime New York Times reporter, is now an associate professor of journalism at New York University. She is the author of “American Tapestry: The Story of the Black, White and Multiracial Ancestors of Michelle Obama” and co-author of “Unseen: Unpublished Black History From The New York Times Photo Archives.”

The 1838 sale had helped save Georgetown and support other Catholic institutions. But what about the Black men, women and children who were ripped away from their families and the homes they had known?

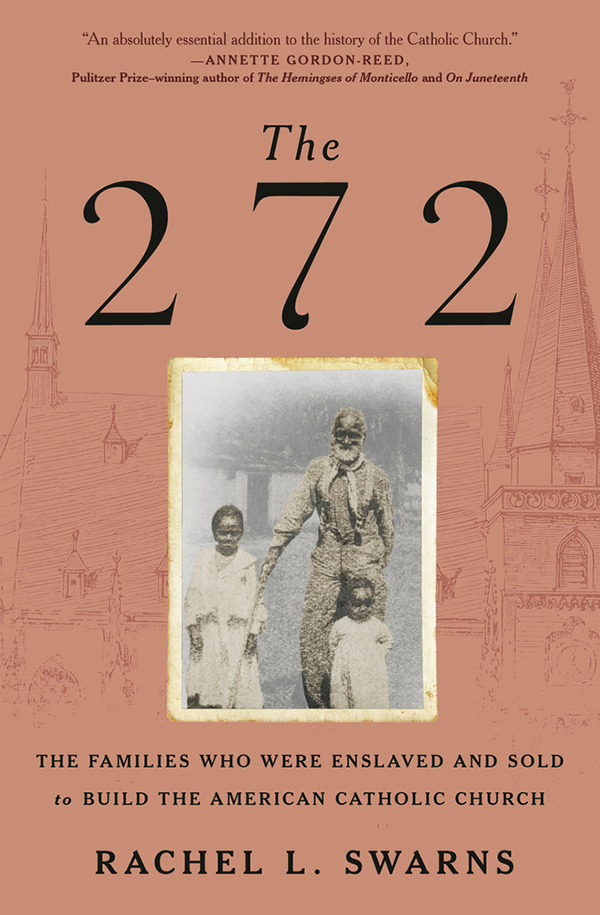

Swarns’ new book, “The 272: The Families Who Were Enslaved and Sold to Build the American Catholic Church,” follows the story of two sisters, Anna and Louisa Mahoney, who traced their family to the 1600s. One sister managed to escape slavery; the other did not. And they never saw each other after the sale. Louisa remained in Maryland, and Anna was sent to Louisiana.

Swarns rebuilds their family story using historical sources and the tradition of storytelling that kept the oral history alive through the generations.

She spoke to Faith & Leadership’s Sally Hicks about the book and how she views this story, as a Black Catholic herself. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: What does this particular story tell us about American institutions?

Rachel L. Swarns: It really shows the connections between slavery and our contemporary institutions. Slavery fueled the growth of so many of them: religious institutions, universities, banks. My book is obviously focused on the Catholic Church, but there’s a reckoning going on about slavery in Protestant churches right now as well.

F&L: Your book focuses on a mass sale of 272 enslaved people in 1838. What made this particularly significant?

RLS: I was at The New York Times, and we got a tip from a Georgetown alum who was pitching a story about a slave sale in 1838 that benefited Georgetown University — a slave sale by Catholic priests.

I am a journalist, but I also happen to be Black and Catholic, and I had no idea.

The stories that I did after that became the point of departure for the book. It was one of the largest documented sales of people at the time. And “GU272” became [a rallying cry], both for the thousands of descendants who have now discovered their ties to the history and for the college students at Georgetown, who got this all going by protesting the names of the priests that adorn the buildings.

I wanted to tell the story of these families, enslaved families. Two sisters were torn apart by this sale, and then I realized there’s this whole family line.

F&L: The story really focuses on one family, the Mahoney family. One thing I found moving in the book is what’s missing. Over and over you write that we can’t know what someone felt — we don’t have a record of what the enslaved people thought. Was that heartbreaking for you?

RLS: On the one hand, the Jesuits kept an enormous, enormous amount of records. And if you’re looking at the 19th century, you’re looking for letters and journals and newspaper accounts.

Enslaved people, by law and by practice, are barred from learning to read or write, and newspapers don’t chronicle the notable things in their lives. So you are piecing together fragments. For a journalist and for a researcher, it’s the most frustrating thing in the world.

I realized a while ago, because I did the book about Michelle Obama and her family, that the absence is part of the story. You wring your hands, you pull your hair, but it’s part of the story. It’s part of the marginalization of these folks; it’s part of the erasure, right?

Part of what I’m doing is little bits and pieces, gathering up as much as I can and trying to thread something together.

F&L: Has it changed your faith or your attitude about the church?

RLS: This is my second book focused on slavery and contemporary reckonings with slavery. I feel like I was a reasonably educated person, and I just didn’t know.

What’s so interesting about the Catholic Church, which relied on slave labor and the slave sales, was that they also believed that people had souls. Really, it’s a kind of crazy thing to think about. On the one hand, they believed in tending to the souls of these people, even as they were buying and selling their bodies, right?

So it is agonizing sometimes. I’ve been doing this for a long time; I know what I’m likely to find. But still, at times, it’s hard history.

On the other hand, though, the Mahoneys and so many of these enslaved families who were sold by the Jesuits and enslaved by them had a choice to make in 1865. Would they stay [in the church] or not? And many, many of them stayed. Not only did they stay, but they then went on to be lay leaders, and some even religious leaders, to try to make the church what it claimed it was — a true universal church — and to make it reflective of the Black parishioners.

To me, as a Black Catholic, that’s inspiring. I grew up in New York. The church I grew up in was a largely Irish and Italian church, and it’s meaningful to me to know that there is this long history. History full of heartbreak, yes. But also love, family, resistance, faith.

F&L: It was fascinating to me how many formerly enslaved people stayed Catholic after the Civil War.

RLS: A lot of the descendants of these folks who were sold in 1838 stayed. In fact, some of the best records for genealogists who have been trying to track the families — like the Georgetown Memory Project, which has dedicated itself to trying to literally track down descendants of all of those 272 people — the sacramental records post-Civil War have been enormously helpful.

I think, for a lot of these families, the church was bigger than those men — it was bigger than those priests who enslaved them. Those guys didn’t own God, the Son or the Holy Spirit.

There are two notable members of the Mahoney family who become nuns, and one in particular a very notable mother superior in New Orleans — both of them running schools. People working to open Black parishes, becoming lay leaders, teaching catechism in Sunday schools and parochial schools.

People really engaged and really held on to their faith.

F&L: What impact did the money from the sale have on the Catholic Church in America?

RLS: The priests who built the foundations of the Catholic Church relied on slavery and slave sales to build all kinds of systems. Georgetown, the first Catholic institution of higher learning, the first archdiocese, the first cathedral. The early institutions of the Catholic Church were built by priests who relied on slavery.

Moving ahead to 1838, the priests who wanted to make this sale had this notion — and they were right — that this church built on a rural plantation model was not the future. The future was the cities, where immigrants were pouring in. The future was the possibility of expanding beyond Maryland, expanding and building schools across the Eastern Seaboard.

There are a number of colleges that benefited from that sale. They sold these people, saved Georgetown and were able to help a number of institutions. Loyola University Maryland and Holy Cross did their own report and have acknowledged that they received money from the sale.

And then there were a number of institutions that benefited in other ways, not in direct money, but the Jesuits of Maryland, because they were the cradle of the Jesuit universe in the United States, provided faculty and training and support to a number of institutions — St. Joseph’s in Philadelphia, Boston College, Santa Clara in California.

F&L: From the Jesuit point of view, it was a success.

RLS: Oh, it was a success. The priest Thomas Mulledy, who served both as a president of Georgetown and then as a leader of the Jesuits province, he was a visionary in a way. He could see what a lot of other people who were still rooted in this rural plantation framework couldn’t see. And he was right. It just came at a terrible, terrible, terrible cost.

F&L: Your writing is very historical and evenhanded, but if there’s a villain, it’s him.

RLS: He was a strong personality. Anyone who knew him and described him, described him that way. In his own letters, the personality burst off the page. He was an interesting and clearly charismatic person.

F&L: There aren’t too many white people who are heroes in this story, but Joseph Carbery comes closest. Your book shows the difficulty of maintaining the fiction that Black people aren’t human. As you noted, they’re selling Black bodies but saving Black souls.

And the logic of selling them to Louisiana — it was the worst place to be enslaved, yet their logic was they could still be Catholic, so it’s OK. What do you make of these contradictions?

RLS: Joseph Carbery is a good person to talk about. He’s a 19th-century figure, but even in the 18th century, there were people who raised concerns and raised questions.

Catholics who built the foundations of the church in Maryland were persecuted themselves. There were laws that restricted their participation in public life. And part of being an establishment, part of being part of good society, [was that] the wealthy, prominent people were slaveholders. I think all of those things played into it.

And then, frankly, it was the economy. Money, financial considerations. It’s important to note the Catholic Church was not alone in this; Protestant churches also were fine about the enslavement of Black people.

But there were these voices, and complicated ones. Joseph Carbery came from this prominent Maryland family, who had their own ties with slaveholding, but he could see it.

He wrote about the skill that some of the craftsmen had; he described a windmill that someone built and how well it was made. He described the humanity of people and their faithfulness. He gave the people on the plantation that he managed a lot of autonomy.

And so when the sale came in 1838, he protested, he had people praying about it, and when he couldn’t stop it, he urged people to run.

The complexity of Joseph Carbery is that he encouraged people to run away, and they did. [Then] the slave ships departed, and he welcomed them back into slavery, where they remained until the end of the Civil War.

He was like a midlevel manager of a corporation. He didn’t really have the power to free people, but he may well have thought, “Well, this was the right course of action to keep them from being sold, which was a brutal, awful thing to do.” And then the familiar paternalism: “I treat my people well.”

F&L: Why do you think this history is buried?

RLS: It is hard for me to understand, to be honest with you, given how significant slavery was to the emergence of the church. I can say that certainly this history in Catholic circles and among historians of the period was known. There is a book on Jesuit slaveholding that came out in the early 2000s; it was written by a Jesuit priest and scholar. That book, though, was written about the Jesuits. It was a really important book, but the people themselves did not figure prominently in terms of their lives and their stories.

F&L: Where do things stand now with the calls for reparations from the church and the university for the 6,000 or so descendants?

RLS: Both Georgetown and the Jesuits have moved to try to grapple with this history. Both have apologized for this history.

Georgetown, early on in 2016, decided to offer what is the equivalent of legacy status, preference in admissions, to descendants. And they changed the names of the buildings. They also have a fund of $400,000 a year, which they’ve committed to raising from alumni, to fund projects that support the descendant community. They actually have a new institute on slavery that just got up and running.

The Jesuits partnered with a group of descendant leaders and announced a foundation that they said would raise up to $100 million to support racial reconciliation projects and support the descendants.

And then there are other efforts. The Archdiocese of Baltimore has created a commission to look at its history. Loyola University Maryland is looking. A number of things are bubbling up. And it’s all part of this wave of experimentation around the country, as institutions, municipalities, the state of California are trying to figure out, “What do we do? How do we make amends?”

F&L: Is there anything you would want to add that I didn’t ask about?

RLS: History is a battleground right now in our country, especially history around race and around slavery. And I think it’s important for us to know about these ties to our contemporary institutions. We like to think about slavery as something that is so long ago [it has] nothing to do with the world around us.

It’s important for us to know and to acknowledge that and to be able to see and hear about the people who were affected. To get a sense of who they were and what their lives were like. And to know their names.