Editor's note: This conversation took place before hurricanes Helene and Milton devastated the Southeastern U.S.

It was the end of the hottest year on record, when fossil fuel emissions had hit a new high. But when a draft plan was released at the December 2023 United Nations Climate Change Conference, it did not call for a swift global phaseout of fossil fuels.

Climate activists reacted with alarm. Without such a phaseout, it was unlikely the world could limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius — a threshold beyond which scientists say the Earth may not be able to adapt.

The Rev. Dr. Becca Edwards had traveled to Dubai to observe the conference, called COP28, and that evening, she posted a reflection on her blog.

“As people of faith, we should be the loudest voices in the room calling for a phaseout of fossil fuels,” she wrote. “We should not let up the pressure on our elected representatives until they agree to fight for just, equitable, and effective climate policy.”

In response to the tremendous pushback by climate advocates, the final report included language calling for nations to accelerate efforts to transition away from fossil fuels. Edwards later posted an update to her blog, concluding with: “For me, this evidence of the power of public witness is one great outcome of this year’s COP.”

Edwards, the climate action fellow at the nonprofit Texas Impact, educates and empowers people of faith to demand solutions to the world’s most pressing environmental problem. Texas Impact helps faith communities advocate for policies that align with their values. It’s also the Texas affiliate of Interfaith Power & Light, the national interfaith climate advocacy group.

Edwards earned a doctorate in wind science and engineering and taught environmental science at a small liberal arts college in Texas for a decade. She observed that when students understood the science behind climate change, they saw it as a scientific issue rather than a partisan one. In fall 2020, she left academia to earn an M.Div. degree, and earlier this year she was commissioned as a provisional deacon in the United Methodist Church. Her UMC appointment encompasses both her work at Texas Impact and similar advocacy through the denomination’s General Board of Church and Society.

Edwards has met clergy who are concerned about climate change but don’t know how to start a conversation about it with their congregations. She also has met laypeople who care deeply about the issue but see it as a cause separate from their faith. She uses her position with Texas Impact to connect the dots.

In Science at the Seminary, a program she presents at her alma mater Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary, she explains basic climate science and offers theological perspectives on climate change. When she visits Texas churches as an invited preacher or guest speaker, she gives laypeople an overview of the science and illuminates how climate change affects their ministries.

“The way we love our neighbors requires that we understand climate change,” she said.

Edwards spoke with Faith & Leadership contributor Robyn Ross about how she helps people make the connection between their faith and climate action. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: Why do you think people see climate change as separate from their faith? How do you articulate the connection?

Becca Edwards: The popular understanding of the relationship between science and faith is that they are somehow in conflict. The perception may stem from the conversation about the teaching of evolution in schools, and that has led to misunderstanding of how our faith can inform our perspective on other scientific issues. I think of science as being a tool that we can use to better understand God’s creation that we’ve been given. It can inform how we care for that world. It’s a tool that helps us better live out our faith.

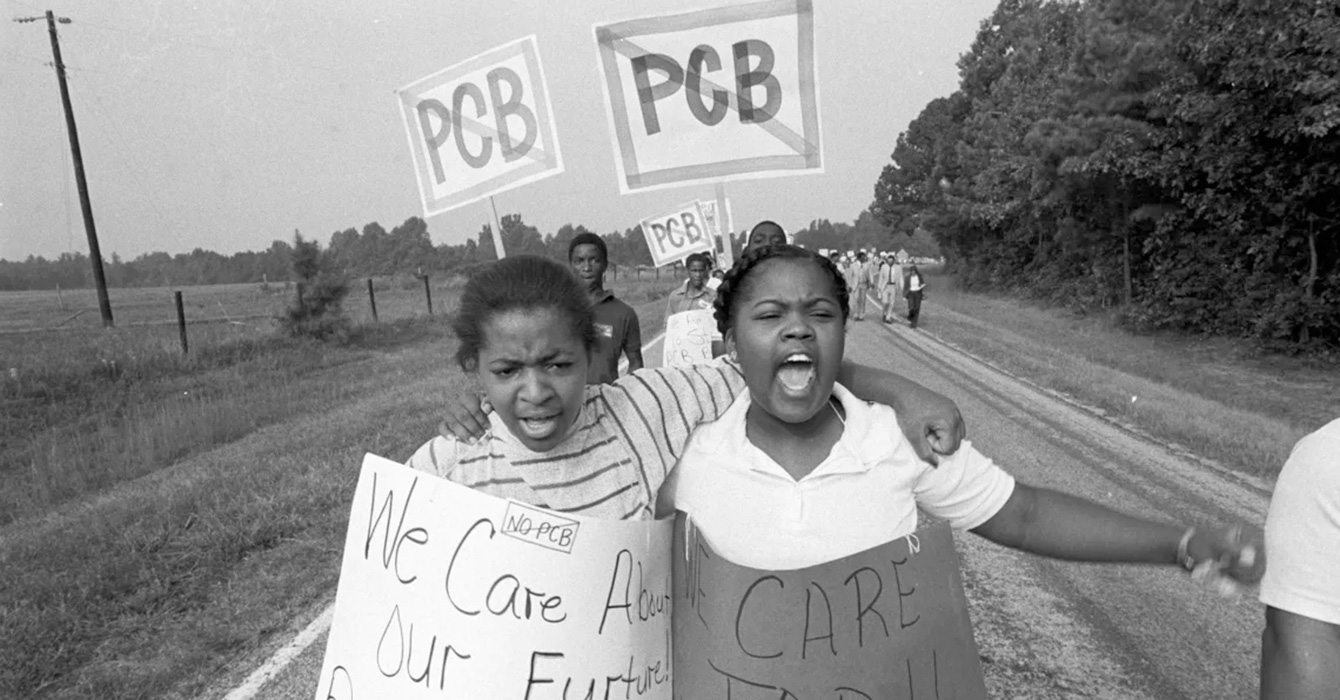

Many scientific issues are justice issues. And issues related to environmental science — challenges with air quality, water quality, soil quality and climate — have major implications for people’s ability to thrive. Liberation theology offers a useful frame for this conversation.

Gustavo Gutiérrez described poverty as an issue of oppression, and you can think of environmental degradation the same way. When we allow corporations to pollute the air and the water, we are creating conditions where people, especially those of lesser economic means, are not able to live in health and dignity.

The Scriptures call Christians and people of faith to resist those conditions of oppression so that everyone can thrive.

F&L: How do you define climate justice?

BE: Climate justice is predicated on the idea that the people who are least responsible for the emissions that lead to climate change and who are least able to adapt to a changing climate are experiencing its worst impacts.

Domestically, that would be unhoused people, people with limited economic means and people with health issues. The disparity is more pronounced internationally. Nations that have contributed very few emissions, mostly in the global south, are experiencing significant climate impacts, such as catastrophic drought and sea level rise.

Countries, such as the U.S. and China, that are big emitters of carbon dioxide have benefited economically from petroleum exploration and recovery in ways that have raised our standard of living far above other places in the world. Our wealth enables us to adapt to climate impacts in ways other nations cannot.

Climate justice would encourage us to say, “We have benefited from this, and now other places are suffering because of it. So what is the most just way to address that disparity?”

One way is through the United Nations Loss & Damage Fund. Developed countries contribute to the fund, and less resourced countries that are experiencing climate impacts use it.

F&L: How is climate change affecting the work of the church?

BE: International ministries are contending with intense drought and floods that wreak havoc on agriculture. Disaster relief ministries are stretched thin, because we’re having more frequent extreme precipitation, flash floods and very strong hurricanes. The church is involved in health care, and climate change leads to an increase in vector-borne diseases such as Zika and chikungunya.

All our ministries have a limited budget, and understanding how climate change is affecting the communities we serve allows us to use that budget in the most effective way possible.

Climate change is affecting us at home too. Many churches in Texas, especially in the United Methodist denomination, recently lost their property insurance because of the increased incidence of extreme weather causing property damage. They had to find new insurance that had much higher premiums. This was an unexpected expense that, at least in my congregation, required some changes to church operations that were very difficult.

F&L: How is extreme heat — which we’ve experienced this summer in Texas — simultaneously a climate and a justice issue?

BE: Extreme heat is a major stressor on both the physiological and psychological systems in the body. It causes cardiovascular and respiratory issues, and it’s also correlated with increased violent crime, domestic violence, mental health incidents and suicide attempts.

Climate change raises temperatures and creates very high heat indices. It also raises the nighttime lows. When the nighttime low doesn’t drop below 80 degrees, the body never has a chance to recover from daytime heat.

This has big implications for the unhoused people our churches serve, as well as the elderly and other people with limited means to air-condition their homes. In Texas, a significant number of prisons are not air-conditioned, creating very hot and unsafe conditions.

F&L: Many congregations are eager to adopt sustainable practices — to switch to renewable energy or replace Styrofoam cups with reusable mugs. What role do these efforts play in climate justice?

BE: Numerous congregations in Austin are doing great work in this area. One installed a solar array on their parking garage. My own church has been composting the waste from our breakfast for people experiencing homelessness. These are important steps that make a visible difference, set a good example and have ripple effects. If your church stops buying Styrofoam coffee cups, you’re no longer supporting that industry.

Still, the “carbon footprint” model of thinking about the environment places all the responsibility on the individual person or church. It pushes you to think about your own house, your own electric bills and so forth. Your consumer choices are important, but we neglect the systemic level of response to climate change when we focus too much on individual choices.

For instance, 36% of the carbon emissions in the state of Texas are industrial, while less than 2% are residential. Even if you’re able to make big changes within your own home — or church — the fraction of the emissions that you produce is so small that it’s dwarfed by the industrial contribution.

We need to push for systemic changes like reducing our industrial emissions as a state and using more renewable energy. We can make better consumer choices while also becoming advocates, because the actions that will most effectively combat climate change are at a policy level.

F&L: How do you, in your work as the climate action fellow, encourage people of faith to push for systemic change?

BE: I have spoken to legislative staff in Washington and Texas, while wearing my collar, about issues such as renewable energy, transit, strengthening the grid, limiting methane emissions and protections for outdoor workers. Some have been surprised that a person in a collar is interested in climate change mitigation. But we know that many people of faith are concerned, often because these issues disproportionately affect marginalized groups.

At Texas Impact, we have a climate action team that anyone can join. It meets weekly, and we talk about opportunities for engagement at the state or federal level. In January, when the Texas Legislature convenes, I’ll send alerts to this group letting them know how to provide feedback on bills.

Texas Impact also will partner with United Women in Faith, the organization that began as United Methodist Women, on an advocacy training and lobby day. And my weekly blog examines policy issues related to climate and energy.

F&L: Can you give an overview of the Science at the Seminary series you developed?

BE: Having seen how familiarity with climate science helped my college students understand the problem in a nonpartisan way, I wanted to demystify it for future and current faith leaders. And I wanted to give people who do theology for a living an opportunity to make connections between theology and science in a way that will inform their own preaching and teaching going forward.

Our first meeting was called “In the Beginning,” and we discussed creation, providence and sin. Then we covered the greenhouse effect. We talked about climate change as an example of human sin, as a deviation from the goodness that God created in the world.

The second one was called “Learning From the Past.” We talked about scientific methods of learning about past climates, and we learned from past peoples by looking at the Israelites and how they understood their call from God to care for the environment, which meant they were caring for one another.

The third session was “Interconnection: How Human and Earth Systems Affect Human Experience.” We talked about how Earth system models are used to understand how different parts of the Earth interact. Then we talked about how changes in those Earth systems caused by climate change affect human systems. And we looked at what liberation theology can teach us about responding to climate change.

We’re creating a curriculum for people who are interested in having this conversation in their own communities. It will be shared on our website.

F&L: How do you find hope amid the discouraging news about the climate and humans’ reluctance to take action?

BE: Hope is one of the biggest gifts that the faith community can give the world, because we have the language to talk about it. We have many historical or scriptural examples of times where things seemed especially dark and hopeless and God was able to create some kind of positive outcome or light in the darkness.

One such example is the exodus, where the Israelites were living in terribly oppressive conditions and God miraculously intervened and worked for their release. There are many scriptural models of a God who’s interested in our liberation and in humans living in conditions where we can thrive. The liberation theologians and womanist theologians also have much to say about holding hope in the midst of suffering.

As a Methodist, I know the Holy Spirit is working through individual people, and we get to work alongside God in bringing about change. We are not just holding hope and waiting but recognizing that our faith compels us to push for justice. We can be part of that movement toward a world where there is less suffering. Working for climate justice, in my opinion, is a big part of that.