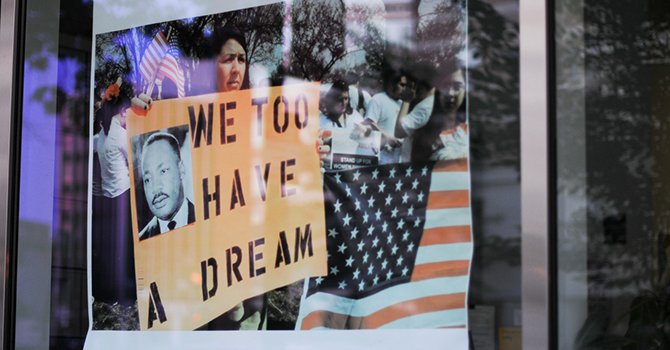

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and with the resurgence of clergy engagement in social justice movements, it’s a natural moment to assess the legacy of King’s leadership, said Leah Gunning Francis.

Part of that is drawing an accurate picture of King, and not placing him on such a pedestal that today’s leaders feel intimidated.

“None of us will ever measure up [to a superhuman image], so let’s not even set that model as a goal,” Francis said. “Instead, let’s take seriously the phrase ‘power to the people’ and embody the spirit that calls us to look for the leader within, that calls us to reach out to others to join together, to form coalitions, to make change right where we are. That’s where I think this movement is calling us.”

Francis is vice president for academic affairs and dean of the faculty at Christian Theological Seminary in Indianapolis. Before that, she served as assistant professor of Christian education and associate dean for contextual education at Eden Theological Seminary in St. Louis.

She is the author of the book “Ferguson and Faith: Sparking Leadership and Awakening Community.”

Francis spoke with Faith & Leadership about King’s legacy, and about a two-part course she and CTS professor Robert Saler are teaching during the 2017-18 academic year that pairs travel and study related to the 500th anniversary of Luther’s promulgation of the 95 Theses in Wittenberg and the 50th anniversary of King’s murder.

The following is an edited transcript.

Q: What do you want to teach about the connection between these two events, these two anniversaries?

I was so intrigued by the fact that you had the legacies of Martin Luther and Martin Luther King coming to the forefront at the same time. How can we not connect these two?

But beyond the name and the optics of it, we saw this as a moment in time in our nation and in the world writ large when we have very clear and distinct concerns related to the direction of our country, civil rights and the well-being of marginalized people.

What are some of the issues that we can look at today and say, “We need the church to be a voice in speaking out, in providing a kind of moral compass, moral authority”?

What can we learn from these two reformers that might influence our thinking -- if nothing else, inspire our thinking -- about how we engage in social transformation?

You still have people that feel that the work of the church and social issues are separate and distinct matters -- that clergy don’t necessarily have a role in engaging in public issues, political issues. I disagree.

In my book “Ferguson and Faith,” I really confront that notion and demonstrate the ways in which clergy were actively engaged in the movement for racial justice in Ferguson after Michael Brown was killed by a police officer. It was their faith that fueled their actions.

Over the years, we have seen clergy emerging in ways that perhaps have not been as visible since the civil rights movement.

Now we know that clergy were not the only people active in the civil rights movement. Several times in Ferguson, some of the younger people would say, “This isn’t your grandmama’s movement; this isn’t your granddaddy’s movement.”

And I would have to kind of hold up a finger and say, “Well, actually, it is.” Because as we look at the civil rights movement of the ’50s and ’60s, it was young people that were very engaged and active and leading the way.

We look at the Children’s March; we look at SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and the role that they played in organizing the Freedom Riders and voter registration and on and on.

So young people, college people, high school students have long fueled these movements for civil rights, for racial justice.

Remember that Dr. King was a young man. He was killed at the age of 39. So his entire ministry, he was a young person.

A lot of older people in the ’50s and ’60s had many of the same or similar concerns that some older people have today -- this sense of taking stock of what there is to lose over against what’s to be gained. As people get more comfortable with jobs and homes and all of this, they may feel like it’s not worth the risk.

But what these current movements for racial justice are calling us to see is that we’re already in trouble. We need to take the risks. And it has been this type of pushing against the system that has enabled things to get as far along as they have. But there is still a long way to go.

So as a seminary dean, thinking about curriculum and the role of theological education in equipping transformative leaders for church and society, how might we glean some of the reforming spirit of a Martin Luther, of a Martin Luther King?

We are stepping into a historical stream. We’re not just starting this movement now; we’re actually picking up and continuing movements that have started long, long, long before us.

And unfortunately, some things have not changed. It is quite ironic that our conversations about MLK’s assassination are being held during the aftermath of Charlottesville.

This kind of blatant expression of white supremacy hasn’t largely been seen since the civil rights movement, and 50 years later, it has resurged with a vengeance.

There is no longer a need to wear hoods and robes. This generation of white supremacists feels confident enough that they have the tacit support of the federal government, and they do not fear any criminal or social repercussions for showing their faces.

Q: We’re getting to the point where people under the age of 60 have few or no personal memories of Martin Luther King, let alone the people who worked with him directly. What do you need to teach as that generation begins to disappear?

We need to tell accurate stories. We’re all clear about the ways in which history has been revised and retold -- ways that have not been accurate. That first-person-account story is waning by the day.

We have the museums in Birmingham and Memphis and Atlanta, and now the new museum in Washington, D.C. We need to keep curating these stories in an attempt to depict as factual a narrative as we can.

I grew up in New Jersey in a home that was very much awake and aware of what had happened throughout the civil rights movement, which mostly concluded right before I was born.

My parents talked about their college experiences and ways in which they found themselves in protests and in movements when they were in college and beyond. My mom grew up in Pulaski, Tennessee, one of the starting places for the mobilization of the Ku Klux Klan, and had very vivid memories of growing up in that type of context.

But growing up in a home where a broader narrative was taught was not necessarily the norm for all people in this country. There were things taught in school about Dr. King’s dream, but that was pretty much the extent of it.

And it was really positing him as this semi-angelic deity who had this very lofty dream of an America where all black people and white people could live together and children could walk hand in hand together.

But there was very little teaching about Dr. King’s speech on the Vietnam War and the Poor People’s Campaign. And so this image of King does not come close to telling the fuller narrative of King’s work.

And in addition to that, it also holds him up as the one leader of a movement. As if when Dr. King was killed, when the Civil Rights Act was signed, that’s it -- “OK, we’re done here. This is over.”

There are many problems with that. Let me just identify a couple. One fact is that King was not the sole leader of the civil rights movement. There was a ground game by reformers that included young people, that included women.

So now that more of those stories have been told, it has helped to fill out the civil rights movement narrative. This is so critical for people to understand today, lest we look at current movements for human dignity and civil rights and racial justice and get asked, the way we did in Ferguson, “Who’s in charge? Nobody is in charge of this movement?”

And my consistent response was, “This movement is one where leadership emerges from the ground up; it’s not just a mythical figure to point the way, as they posited King.”

This movement for justice and freedom for black people in this country never should have been -- nor was -- about just one deified person. Looking for this person to be superhuman sets the whole thing up for failure.

As I’m out speaking on “Ferguson and Faith,” and especially when I’m talking with college students and seminarians and young people, what this movement has taught me is that we need to find the leader within.

We need to call out the leader within and to look for opportunities to engage in transformative acts for justice right where we are and to align ourselves with other people that are seeking to do this kind of work.

None of us will ever measure up, so let’s not even set that model as a goal. Instead, let’s take seriously the phrase “power to the people” and embody the spirit that calls us to look for the leader within, that calls us to reach out to others to join together, to form coalitions, to make change right where we are. That’s where I think this movement is calling us.

Q: Talk about the course you are teaching that explores Martin Luther and Martin Luther King.

We’ve completed the first phase of the trip, where we traveled to Germany and Rome.

To be able to go to these places where Martin Luther lived and worked and walked and had his family, to bring it to life as much as possible for our students, was really important for us.

He is one of the most famous reformers in church history; however, he was still a person.

An important goal for us was to be able to see Martin Luther as a person, and go into the churches where he preached and go into the quarters where he lived, and hopefully to challenge them to reflect on their own space and time and what their own particular context might be calling them to.

And it’s going to be a similar thing when we walk in the steps of Martin Luther King in March. We’ll travel from Atlanta all through Alabama and into Mississippi and conclude at the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis.

As we’ve already said, King has been deified. But we’ll be able to go into the churches where he preached, to go onto the Edmund Pettus Bridge where he and thousands of others marched across, to go into Mississippi to the site where Emmett Till was killed, and to put those things in context, to remember Dr. King in the context of his humanity.

These events loom so large. But to go into these itty-bitty small towns and these very rural, dusty spaces -- we hope that the struggle becomes that much more real for them.

These were just ordinary people trying to do some really extraordinary things for the purpose of freedom and the fight for racial justice.

So this is what we hope our students take away: to be inspired and to glean some important insights into these people’s lives that they might be able to take and apply to their own lives -- how they, too, can be reformers for freedom and justice in this time and space where they live.