The melodious voice of Howard Thurman bellows through the room: “How good it is to center down,” he says. His voice is filled with gravity, but it is not without a sense of joy. It has an almost incantatory quality, a cadence both warm and mysterious. Each time I play a recording of Thurman reciting one of his many meditations, I smile. Like Landrum Bolling writes, many of us feel like Thurman speaks directly to us — “vividly, intensely, personally.”

Once I started reading and listening to Thurman, I stopped feeling strange for seeking silence, stillness, and solitude. My awkwardness as the only African American on a silent retreat or at a spiritual conference dissipated. In him I found support for my desire for intimacy with God and hunger for spiritual community, and I began to consider him a mentor.

Thurman personally mentored and inspired many social and political activists, among them Pauli Murray, James Farmer, Bayard Rustin, James Lawson, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Jesse Jackson, Marian Wright Edelman, Vernon Jordan, and Vincent Harding. Legions of individuals — faculty, staff, and students at Spelman College, Morehouse College, Howard University, and Boston University; members of the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples; those in attendance at Sunday worship at Marsh Chapel; and the readers of his books and listeners of his catalogued lectures and sermons — have absorbed his quiet and determined direction. Something in his rich, poetic voice and profound wisdom speaks to the deeper places within us.

Being mentored by Thurman or someone else, however, does not mean we simply stop there. As those who have been mentored, we are called into mentoring others.

Thurman’s Mentors

Born into a community of trusted guides, Howard Thurman understood the importance of having a spiritual mentor and, eventually, of being one for others. “For Thurman, real learning always required the intimacy and intensity of personal mentoring,” write Quinton Dixie and Peter Eisenstadt. “He had always sought out teachers who could provide this, and he would try to be that sort of teacher himself, giving several generations of students the same sort of close spiritual encounters that had been so important to him.” Howard Thurman needed spiritual mentors to reach the apex of his potential, and he blossomed into his role as mentor. Prominent people dotted young Thurman’s surroundings, including the family physician, John Stocking, and renowned educator and activist Mary McLeod Bethune. Yet his grandmother Nancy Ambrose, Mordecai Wyatt Johnson, George Cross, and Rufus Jones served as his chief mentors. Let’s look at how these individuals molded and shaped him and his thinking.

Grandma Nancy

Grandma Nancy served as Howard Thurman’s first mentor. She pushed him to develop his mind and live from his spirit. A close friend of Thurman’s, George Makechnie, notes, “Grandmother Nancy was Howard’s rock. Her spiritual strength, wisdom, and good sense had a profound influence upon his growth, shaping, and development.” Makechnie highlights, as Thurman himself did, the way he would read to her from scripture. I imagine him sitting beside her, how proud he must have felt, how precious were these moments he shared with her. She could not read, Makechnie writes, but “she firmly believed an education was of primary importance, and especially so to Blacks. ‘Your only chance,’ she told Howard, ‘is to get an education. The white man will destroy you if you don’t.’”

A tale about Grandma Nancy’s redemptive love demonstrates something of what she modeled for Howard. The story circulates today in sermons and lectures, although it’s hard to know whether it actually happened. Still, the story holds value for what it evokes of Grandma Nancy’s character. When Howard was a child, a white woman who lived adjacent to their home apparently resented having Black people live near her. Each night she dumped chicken manure she had scraped from her chicken coop over the fence onto Grandma Nancy’s garden. Young Howard wondered why his grandmother did not become enraged at her neighbor’s hateful act and exact some sort of revenge. Grandma Nancy chose instead to rise early and mix the manure into the soil and use it as fertilizer. This practice continued for years.

One day the old white woman, who lived alone, became ill. Being an authentic Christian, Grandma Nancy stopped by her neighbor’s house with some chicken soup and a bouquet of roses. The woman was deeply moved by Grandma Nancy’s acts of kindness and asked her where she had found the beautiful long-stem red roses. Grandma Nancy Ambrose told the neighbor that she herself had played a role in growing the beautiful roses. She reminded her about the chicken manure she had dumped regularly in her backyard.

The God Grandma Nancy worshipped showed her how to turn hate into love. Thurman espouses this form of redemptive love in Jesus and the Disinherited, in which he reminds his readers that Jesus treated people not in proportion to who they were but to who they could be. Thurman knew that healing a fractured nation would require this type of transformational love.

Mordecai Wyatt Johnson

While attending the Florida Baptist Academy, Thurman joined the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). Although highly segregated, the YMCA created programs for the uplift of boys and young men. His election as president of his local chapter during his sophomore year allowed Thurman to attend his first King’s Mountain conference where he heard the great orator Mordecai Wyatt Johnson. Johnson had served as a former student secretary of the International YMCA Committee. Howard was so impressed and stirred by Johnson’s message that he wrote him a letter. Despite his earlier ambivalence about the church, due to how it scorned his father’s death, Howard pleaded with Johnson to become his mentor. “I want to be a minister of the Gospel. I feel the needs of my people, I see their distressing condition, and have offered myself upon the altar as a living sacrifice, in order that I may help the ‘skinned and flung down’ as you interpret. God wants me and His precious love urges me to take up the cross and follow Him,” wrote the young Howard.

Johnson wrote back, and they continued their correspondence and personal relationship for many years. Possibly the most important piece of wisdom that Thurman incorporated into his adult life came from Johnson. He told Howard, “Keep in close touch with your people, especially with those who need your service. Take every opportunity to encourage their growth and to serve them. School yourself to think over all that you learn, in relation to them and to their needs. Make yourself believe that the humblest, most ignorant and most backward of them is worthy of the best prepared thought in life that you can give.” Howard Thurman took this wisdom into his spirit, and it directed him throughout his life.

George Cross

As a student at Rochester Theological Seminary, Howard Thurman took several courses taught by George Cross. He also had private conferences with him and was advised by him. Thurman wrote that Cross “had a greater influence on my life than any other person who ever lived. Everything about me was alive when I came into his presence.” In their personal meetings, held frequently on Saturday mornings in Cross’s faculty office, Thurman bantered with Cross, asking questions and making challenges. Cross would listen with great patience, Thurman later wrote, and then would “reduce my arguments to ash.”

George Cross believed in the brilliance of Howard Thurman, but as we saw earlier, he could not grasp the reality of racism, nor the extent to which it tries to annihilate unrealized potential in its victims.

Rufus Jones

As an instructor and mentor, Rufus Jones helped Thurman refine his thinking about the links between mysticism and social transformation. They spent many hours discussing how the inward life is connected to outward experience and how mysticism might expand efforts to remedy international conflict and poverty. Although they did not discuss race, which Thurman viewed as a blind spot in Jones’s analysis, Thurman knew he could use mysticism to alleviate the plight of Negroes. His intense kinship with Jones only deepened his intellectual grasp and personal experience of mysticism.

In June 1929, Howard Thurman wrote a note to Rufus Jones thanking him for “the huge share which you have had in the enrichment of my life during the past five months. I cannot now estimate the significance of the days with you at Haverford.” As a result of Thurman’s work on mysticism or religious experience, spiritual seekers and sacred activists continue to reap the benefits of this unique mentoring relationship.

Thurman carried the lessons and words of these spiritual mentors with him in his mind and in his heart. They would become models for him as he, too, became a mentor for others.

Mentoring Others

Howard Thurman serves as an exemplar for both the formal ministry of spiritual direction and informal spiritual friendship. Mentoring, at its best, is an exchange. Spiritual guides are vital beacons of light on the spiritual path, and once a person becomes spiritually mature, they naturally begin to serve as spiritual mentors for others. Maya Angelou instructs, “When you learn, teach.” Howard Thurman taught and mentored many, although not always in a formal classroom. Students found they could share their personal issues with Thurman and frequently sought him out for spiritual advice. His timeless sermons, public lectures, and written meditations endure because they continue to feed the hunger of the spirit. Let’s look at a few of the people he mentored.

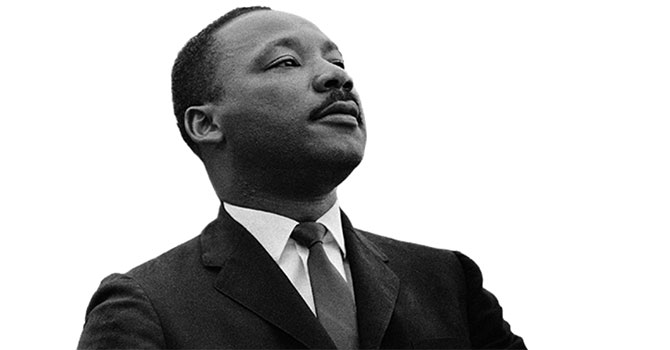

Martin Luther King Jr.

We’ve already seen how Howard Thurman’s indelible mark on the American civil rights movement runs directly through his influence on Martin Luther King Jr. Clearly, the respect went both ways. Thurman expresses his great admiration for King with these words:

As a result of a series of fortuitous consequences there appeared on the horizon of the common life a young man who for a swift, staggering, and startling moment met the demands of the hero. He was young. He was well-educated with the full credentials of academic excellence in accordance with ideals found in white society. He was a son of the South. He was steeped in and nurtured by familiar religious tradition. He had charisma, that intangible quality of personality that gathers up in its magic the power to lift people out of themselves without diminishing them. In him the “outsider” and the “insider” came together in a triumphant synthesis. Here at last was a man who affirmed the oneness of black and white under a transcendent unity, for whom community meant the profoundest sharing in the common life. For him, the wall was a temporary separation between brothers. And his name was Martin Luther King Jr.

Religious scholar Paul Harvey says, “Thurman was a private man and an intellectual; he was not an activist, as King was, nor one to take a specific social and political cause to transform a country. But he mentored an entire generation, including King, who did just that. Thurman’s lesson to King was that the cultivation of the self feeds and enriches the struggle for social justice. In a larger sense, the discipline of nonviolence required a spiritual commitment and discipline that came, for many, through self-examination, meditation, and prayer.” Thurman transmitted that message to the larger civil rights movement.

It was at Crozier Seminary where Martin Luther King took a class from George Washington Davis, one of Thurman’s classmates at Rochester Seminary, and also read and wrote about Thurman’s seminal work Jesus and the Disinherited. King would later incorporate some of Thurman’s notions into some of his own writings and speeches. Although King did not consider himself a mystic, he was moved and amazed by the mystical wisdom of Thurman. Howard and Sue Bailey Thurman expressed hope that King would consider becoming the pastor of Fellowship Church, but King felt called to Montgomery to begin active work in the civil rights movement. Working behind the scenes, Howard Thurman became his spiritual adviser.

One story illustrates their spiritual connection. In 1958, a mentally disturbed woman attempted to assassinate Martin Luther King Jr. by stabbing him. Thurman writes that he experienced a “visitation,” or vision, and knew he needed to travel to New York to speak with King.

Thurman found King at Harlem Hospital and strongly urged him to take a much longer recuperation period and to include some time for silence and solitude. He needed to assess his role in the movement, in a venture that had taken on a life of its own. King later wrote to Thurman about how their meeting had been “a spiritual uplift, and of inestimable value in giving me the strength and courage to face the future of that trying period.” Historian Taylor Branch points out that this time was a period of relative quiet for King, a unique season within the rest of his adult life. There were no talks or lectures, but just solitude. It was after this respite that King took a five-week trip to India, studied the principles of nonviolence and civil disobedience, and laid a wreath at the grave of Mahatma Gandhi.

The ideas about a nonviolent religion and Jesus as a nonviolent liberator that Thurman developed in the years before and during his tenure at Fellowship Church received a larger audience through the publication of Jesus and the Disinherited in 1949. This book deeply influenced other leaders of the civil rights struggle. Thurman offered the vision of spiritual discipline that informed the moral basis of the Black freedom movement in the South. During these years, while serving on the boards of Fellowship for Reconciliation (FOR) and Congress of Racial Equality CORE, he spoke with leaders of these organizations and others — including Bayard Rustin, James Lawson, Vernon Jordan, James Farmer, Pauli Murray, Jesse Jackson, and Whitney Young — about matters both political and spiritual. But Thurman always preferred offering quiet counsel and private intellectual guidance to garnering political visibility. His influence would extend into the future to touch the lives of many religious scholars and scores of spiritual seekers, including Alice Walker and Barack Obama.

Marian Wright Edelman

Like a river, Howard Thurman’s sway flowed along several tributaries, inspiring women and men who chose to devote their lives to important yet sometimes less visible causes. Marian Wright Edelman, founder and president emerita of the Children’s Defense Fund, found kinship with Thurman in the ways in which they were reared. They both emerged from families of deep faith who worked to buffer them from the hostile worlds they would encounter. Edelman writes, “Still, as in the days of Thurman’s childhood and in the day of my childhood, countless children in these most difficult, unjust, undeserved circumstances are bolstered and strengthened, nurtured and protected by parents, and others who struggle to counter the world’s message and remind their children that they are sacred gifts from God and precious in God’s sight.” Her parents, like Thurman’s grandmother and mother, didn’t want her to internalize negative and damaging social messages. Their loving protection gave her a certain inner strength that enabled her to take her prophetic message about the care of children into adulthood.

Edelman first encountered the words of Howard Thurman as a young girl exploring the books in her minister father’s study. Then as a college student, she heard Thurman speak when he visited Spelman Chapel. What kept her grounded in her work to save and support children, Edelman writes, were the urgings to pray, meditate, reflect, and be thankful for grace. In the centering moment, we find a “breath of renewal, and a recognition that we can only do our most faithful best and then turn it over to God. We cannot sustain this work if we are not centered.” Edelman took in Thurman’s words like a holy communion. Meditations of his like “Remember the Children” inspired her to hold “the big hope that never quite deserts me” and to continue in her struggles to end violence, promote love, and protect innocent children from needless suffering.

Vincent Harding

The deep waters of Howard Thurman’s wisdom also touched historian, educator, theologian, and activist Vincent Harding, who considered Thurman a surrogate father. Like so many others, Harding first met Thurman on the pages of Jesus and the Disinherited, which he read as a graduate student at the University of Chicago. Many years later, after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., a close and personal relationship burgeoned between these two great men. Thurman offered solace, care, and guidance in what Harding describes as the gloomy days following King’s death. During many long walks up the steep and winding streets of San Francisco, Harding and Thurman laughed and talked. Thurman invited Harding and his wife, Rosemarie Freeney Harding, to join him and Sue in their home for relaxation and fellowship.

Harding understood that Howard Thurman occupied the important role of mentor and companion to those summoned to the streets to march. As nonviolent demonstrators prepared for action, and when they returned victorious or defeated, Harding writes, “Thurman offered clarification, hope, and encouragement.” Thurman would sit with civil rights demonstrators and listen and pose questions rather than issue commands. He would ask them about what they were seeking and why and what means they utilized to achieve their goals. As a spiritual mentor, Thurman conveyed to them his firm belief that there could be no defeat of the movement if their motives remained oriented toward the oneness.

“I remember going to him in times of deep personal need, occasionally talking by phone, sometimes face to face,” Harding recalls. “He was always solidly present, listening, understanding, admonishing when necessary, sharing silence, surrounding and undergirding me with prayers, doing whatever else seemed helpful. We could feel Howard and Sue keeping our entire family and a special place of love and meditation between them. I remember our silences. They were filled with his wisdom and compassion. Indeed, it may be that he was the wisest and most compassionate man I have ever known.”

The wisdom of life exists to be passed on so that others will not suffer needlessly. A gifted mentor like Howard Thurman spurred people to refine who they already were and to recognize the strengths and talents they possess. Relying on some of Thurman’s words, noted author Sam Keen shares how Howard Thurman encouraged him to find his own vision: “Follow the grain in your own wood.” Peter Eisenstadt observes, “Throughout his career, Thurman was in demand as a mentor and advisor. Counseling is, of course, a core responsibility for all members of the clergy, but Thurman clearly had a special calling for it, less a matter of dispensing advice than assuming the role of a spiritual psychologist, to help others to find their inner voice, what he later called ‘sound of the genuine,’ and to assist them in formulating and answering their own questions.” One of the joys of being a professor for me was advising and mentoring students. I nudged them to try different forms of mindfulness, including meditation, to prevent test anxiety, spark creativity, and prompt innovative thinking. I highlighted the importance of retreats, especially silent ones, to re-energize and guard against burnout and stress. I enjoyed sitting and chatting with students, waiting for that special moment when their eyes would brighten and I would observe them “come alive,” as Thurman describes. The answers I have uncovered in the silence, the stillness, the quietness, the pausing, the “resting lull”: these answers emanate from the same Source Thurman drew from, the same wisdom that must be shared. He will remain my spiritual guide and companion, as his life and words lead me to the Light, to the Wholeness he knew.

Reprinted with permission from “What Makes You Come Alive: A Spiritual Walk With Howard Thurman,” by Lerita Coleman Brown, copyright © 2023 Broadleaf Books.