On a July morning in a classroom at Ohio’s John Carroll University, 25 students brought together by the Ignatian Solidarity Network are sharing their goals for improving the colleges they attend.

Their voices are earnest and their objectives admirable: smaller carbon footprints, more diverse student bodies, sufficient resources for undocumented students and so on.

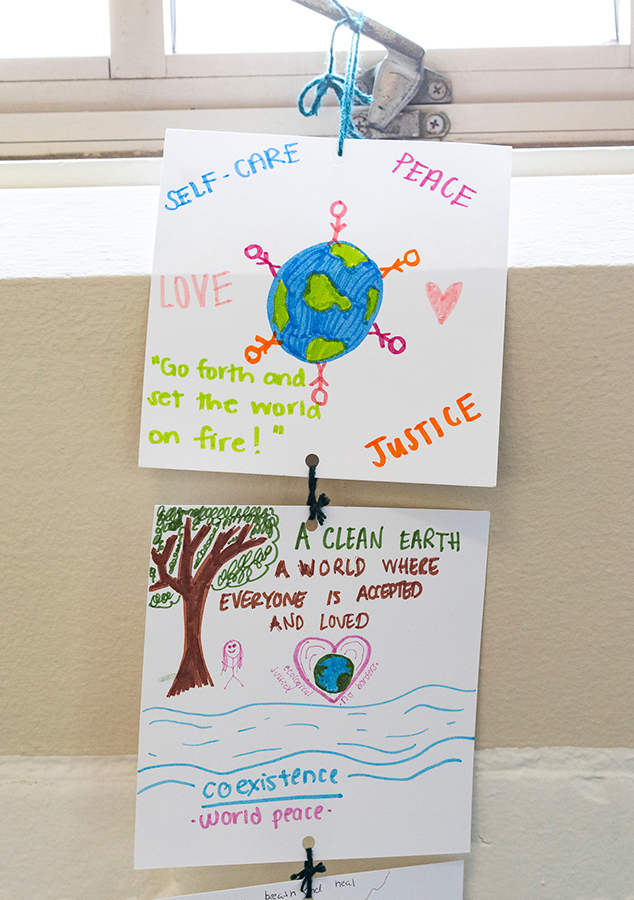

Folding tables along the cinder block walls are loaded with snacks, jigsaw puzzles and progressive literature about everything from global warming to nonviolent protest. Poster boards from the 13 participating Catholic universities at this Ignatian Justice Summit proclaim positivity.

The summit, held at a Jesuit university in suburban Cleveland, can trace its origins to an event at another college thousands of miles away before any of these students were born — not a teach-in, but a massacre. It was 35 years ago that six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper and her daughter were executed on the grounds of the Jesuit University of Central America in El Salvador. The ensuing outrage led to the formation of ISN, which organizes this annual meeting as part of its mission to advance social justice on a variety of fronts.

Made up of 90,000 members and institutions from around the country, most of them Catholic universities and high schools, ISN exemplifies a philosophy that holds the past and future in tension rather than in opposition. Such traditioned innovation can be critical to the growth of Christian institutions.

It is, according to board member Teresa Marie Cariño Petersen, a home for “people who are seeking a better world and who have the faith that the world can be better than it is currently.”

The students were gathered for the summer summit, but ISN’s biggest event is its annual Ignatian Family Teach-In for Justice, held every October, when nearly 2,000 members gather in Washington, D.C., for a weekend of teaching, prayer, networking and advocacy for justice on Capitol Hill. It is the largest annual Catholic social justice gathering in the United States.

“To be a good advocate, you have to do good at home,” said Christopher Kerr, the organization’s executive director. “It will lead to a more just society. I don’t think we’re doing anything different from what we did 20 years ago.”

A massacre that led to a movement

Making El Salvador a better place was the mission for the priests at the Jesuit University of Central America. From 1980 to 1992, the Central American country was racked by a civil war between a right-wing military dictatorship backed by the U.S. and leftist guerrillas supported by Cuba and the Soviet Union. An estimated 75,000 people died, mostly farmers and villagers, many of them massacred by right-wing death squads.

Although El Salvador was — and still is — a predominantly Catholic country, the dictatorship saw Jesuits as a threat because of their outspoken support for the poor and oppressed. The military came to regard anyone supporting the rebels, even clergy, as communists and therefore fair game.

In 1980, Óscar Romero, archbishop of San Salvador, was assassinated in a small hospital chapel in the city as he celebrated Mass. Later that year, three nuns and a lay missionary — all Americans — were raped and murdered near San Salvador by National Guard troops.

Then, on Nov. 16, 1989, an elite battalion of the Salvadoran Army invaded the grounds of the Jesuit University of Central America with orders to kill the Rev. Ignacio Ellacuría, an outspoken critic of the dictatorship, and to leave no witnesses. They executed Ellacuría, along with the seven other people they found.

The killings sent a shock wave through the Jesuit order. Many of the soldiers who participated in the massacre were graduates of the U.S. Army School of the Americas, a facility for training Latin American military and police. Based at Fort Benning, Georgia, the SOA was nicknamed “School of Assassins” by critics who noted the large number of graduates who went on to commit war crimes in their native countries.

SOA Watch formed in 1990, organizing protests outside the gates of Fort Benning and demanding that SOA be shut down. Bob Holstein, a former Jesuit turned labor lawyer, and the Rev. Charles Currie, S.J., emerged as leaders in the protests. Currie, who was elected president of the Association of Jesuit Colleges and Universities in 1997, and Holstein first established the Ignatian Family Teach-In for Justice as an annual event, timed around the anniversary of the massacre, to bring college students together for a vigil and discussions about how to achieve peace in Central America.

What is the good you are doing “at home” to advocate for your community?

Ignatian Solidarity Network among 2023 award winners

Leadership Education at Duke Divinity recognizes institutions that act creatively in the face of challenges while remaining faithful to their mission and convictions. Winners receive $10,000 to continue their work.

Faith and justice

Jack Raslowsky was teaching at a Jesuit high school in New Jersey when the massacre occurred, and he joined the SOA Watch protests. It was while attending Mass in a tent on the banks of the Chattahoochee River, outside the gates of Fort Benning, that he truly felt the connection between faith and justice.

“It’s an identity issue,” said Raslowsky, now the president of Xavier High School in Manhattan and a former ISN board member. “I can’t conceive of this movement for justice not seeing it as a responsibility of the call of my faith.”

Wanting to expand their work beyond protesting SOA, those activists formed ISN in 2004 as a laity-led 501(c)(3) organization for social justice education grounded in Catholic social teaching and focused on forming individuals with a lifelong commitment to the “service of faith and the promotion of justice.”

Though rooted in the Jesuit tradition, ISN is not, strictly speaking, a Jesuit or Catholic organization. It operates independently of the order, though there are Jesuits on the board of directors, and the organizations frequently collaborate, said Kerr. Members don’t have to be Catholic, and ISN accepts LGBTQ+ students and other marginalized populations in a way that the Catholic Church hasn’t always done.

Justice-minded students wary of the church are welcome, said Nicholas Napolitano, the provincial assistant for justice and ecology at the USA East Province of the Society of Jesus and a former ISN board member.

“It’s creating an opportunity where young people can find a space in [the church],” he said.

While there are many nonreligious social justice groups, board member Petersen said she thinks those whose justice work is rooted in faith are less likely to suffer burnout, because their advocacy can tap into something deeper, something “ever-giving and unfolding.”

When have you felt a connection between faith and justice?

A tradition of social justice work

Though only 20 years old, ISN can trace its purpose to the 500-year-old origins of the Jesuit order and the tradition of social justice going back to its founder, St. Ignatius of Loyola. A 16th-century Spanish nobleman who underwent a religious conversion after being wounded in battle, Ignatius renounced worldly things and founded the Society of Jesus on the principles of poverty, chastity and obedience.

Over the centuries, the Jesuits founded hundreds of schools and universities and established missions, dedicating themselves to scholarship, conversion and a muscular form of Catholicism, at times clashing with the church. The Jesuits’ commitment to social justice was reawakened in 1973 when Superior General Pedro Arrupe gave a speech declaring the purpose of education to be teaching students to become “men for others.”

That belief was at the heart of the liberation theology practiced by the Jesuits in El Salvador; service for others is the ethos of ISN today.

Training leaders for today and tomorrow

The students at the John Carroll University summit were not there to plan protests against the SOA, which still operates in Georgia under a new name. They were concerned with changing policies and practices at their schools, such as providing more support for undocumented students, following ethical purchasing practices at campus bookstores and the like. Overheard from one student: “How cool would it be to walk into the cafeteria and know where those veggies came from?”

Over the past two decades, Kerr said, ISN has moved away from direct action, like the SOA protests, in favor of education, advocacy and organization, largely working to effect change at Catholic high schools and colleges. Making changes in school policies and structures is a way to ensure that the improvements are permanent, he said. In keeping with that approach, much of ISN’s work is teaching and inspiring student leaders to return to their schools and continue their work even after graduation.

What does teaching people how to become “for others” mean to you?

The organization concentrates its efforts in three areas:

Economic justice

At the core of this is the Catholic Ethical Purchasing Alliance, which lobbies Catholic high schools, colleges and churches to buy products made in the United States, particularly clothing sold in school bookstores. More than just a “buy local” program, it teaches students how to investigate their schools’ procurement programs and educates them about retail and the struggling U.S. textile industry.

Buying clothing made in this country, as opposed to Latin America or Asia, not only supports jobs but shrinks the carbon footprint of manufacturing and transportation, Kerr said. As a result of this program, bookstores from Fordham University to Saint Louis University now sell sweatshirts and hats made in the U.S., and the University of Dayton includes “the common good” as a criterion when making purchasing decisions.

Migration

ISN’s activities in this area grew out of the massacre in El Salvador and the desire to improve circumstances in Central America and conditions for immigrants, documented or not, to this country.

It’s the issue in which ISN is most involved in national policy. The organization has led trips to the U.S.-Mexico border to listen to migrants’ stories and recently asked that supporters contact members of Congress in opposition to President Joe Biden’s crackdown on immigration. Its Undocu Network has offices on multiple campuses that offer support, resources and advocacy for undocumented and underdocumented students.

How does your community contribute to “the common good”?

Environmental justice

ISN’s activities around creation care and justice range from supporting the Paris Agreement and urging members to support a variety of pro-environmental legislative actions to encouraging students to push high schools and universities to follow more environmentally friendly policies.

ISN holds workshops in Catholic secondary schools, helping administrators collect data on electrical usage and devise ways to reduce it. Eventually, the group plans to help schools create their own power through renewable energy sources.

Activists in the age of social media

In an age when some people think activism is liking a post or retweeting, ISN dives deeper into what is actually required, teaching students the skills they need.

At the Justice Summit, students divide into groups of three. One explains a problem she is trying to solve on campus. She then swivels her chair so her back is to the other two, who discuss possible solutions. They can be heard by the speaker but cannot see her face, which allows them to speak freely, unconstrained by her reactions. The others then take their turns until all three have had their say.

Jacklyn Alonzo Heredia, a junior at Santa Clara University in California who is involved in numerous social justice groups, talks about her frustration with the school administration’s scheduling of meetings at times when it is difficult for students to attend. The two others in her trio offer a variety of suggestions.

“It’s just helpful to get a perspective from students at other schools,” Heredia said after the session. “You know you’re not the only one dealing with issues.”

Other sessions took up learning how to set priorities, how to realistically determine what can be accomplished by students who are in school for a limited period of time, how to assemble the right team, and other lessons in organizing and activism.

The summit was the first ISN experience for Brice Hansen, a junior at Mercyhurst University in Erie, Pennsylvania. The young activist said she would be going back to school with a renewed sense of purpose and possibility.

“It’s a reawakening,” she said. “I don’t see any limits to how we can make a difference.”

How are you gathering other perspectives?

Questions to consider

- What is the good you are doing “at home” to advocate for your community?

- When have you felt a connection between faith and justice?

- Part of the Jesuit commitment to social justice includes teaching students to be “for others.” What does teaching people how to become “for others” mean to you?

- How does your community contribute to “the common good”?

- How are you gathering other perspectives?