The Rev. Eric Manning was caught off guard when his bishop telephoned on a Tuesday morning in June 2016.

“I was in my study and took the call assuming it was about our venue for the upcoming AME annual conference,” Manning said.

Instead, Bishop Richard Norris informed Manning that he was being assigned to Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. Manning recalled his shock, fear, trepidation and excitement, along with his sadness at leaving Bethel AME in nearby Georgetown, a congregation he had served and loved for just a year and a half.

But mostly he felt uncertainty about what lay ahead. He was stepping into a church still recovering from a horrific crime only a year before, a crime that had cost the congregation nine of its members, deeply traumatized the church and its community, and shocked the nation.

“That next Sunday morning from the pulpit of Mother Emanuel, I spoke honestly. I preached from the Twenty-Third Psalm … and said that I don’t know how to lead this congregation, a church that’s had its very foundation shaken, but I will serve and trust that God will lead us. That trust is ongoing to this day,” Manning said.

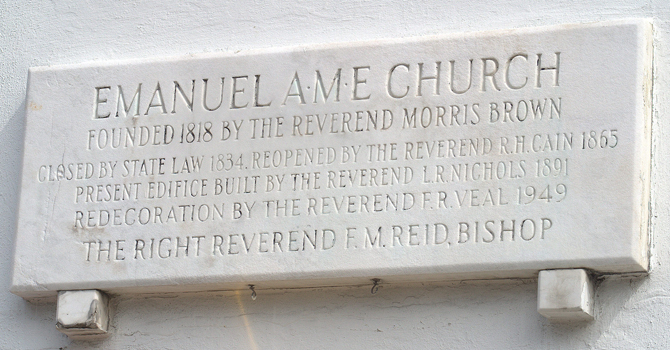

Founded in 1817, Mother Emanuel is the oldest AME church in the South. It’s a site rich in history, where Denmark Vesey planned his famed, failed 1822 insurrection and Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders preached.

But on June 17, 2015, nine church members and clergy were murdered there. The victims included the senior pastor, the Rev. Clementa C. Pinckney, along with Ethel Lee Lance, the Rev. Sharonda Coleman-Singleton, Cynthia Graham Hurd, Susie J. Jackson, the Rev. DePayne Middleton-Doctor, Tywanza Kibwe Diop Sanders, the Rev. Daniel Lee Simmons Sr. and Myra Thompson, who was leading her first Bible study as a fresh AME licentiate.

That evening, Thompson shared reflections on the parable of the sower with 11 friends gathered in the fellowship hall, and with a stranger, 21-year-old Dylann Roof, to whom the group extended a warm, unquestioning welcome.

As they bowed their heads for the closing prayer, Roof opened fire. Five parishioners survived the carnage: Polly Sheppard, Felicia Sanders, and Sanders’ 11-year-old granddaughter, along with Pinckney’s wife, Jennifer, and their young daughter, who were nearby in the pastor’s office.

How did the murders at Mother Emanuel affect the way you think about race relations in America?

Such violation of the sanctity of a church from a violent, racist act stunned the nation and recalibrated people’s sense of security and community across faith traditions. Five years later, Mother Emanuel remains forever changed. Indeed, Charleston’s history has been changed, and is still changing, in the tragedy’s wake.

“We can never be the same again,” said Alphonso Brown, the music director at neighboring Mt. Zion AME.

Outpouring of love

In the immediate aftermath’s glare of international attention, Mother Emanuel became a shrine. Mourners left mounds of flowers, stuffed animals, candles, messages and tributes at her entrance.

Just four days after the massacre, interim pastor the Rev. Norvel Goff held Sunday services at the packed church. And that evening, 15,000 community members from all races and backgrounds joined hands in support and solidarity across the 2.5-mile span of the city’s Ravenel Bridge.

Roof, subsequently convicted and now awaiting the appeal of his death penalty, had hoped his hate crime would incite a race war; instead, it sparked a long-burning blaze of outrage, grief and reconsideration.

In the weeks and months that followed, seeds of change began to grow. Then-Gov. Nikki Haley ordered that the Confederate battle flag be removed from the South Carolina State House grounds. Some Confederate monuments around the South came down; proposals to remove or amend the John C. Calhoun monument a block away from Mother Emanuel are still pending.

People pushed for more stringent background checks for guns and a fix to the “Charleston loophole” that had enabled Roof to purchase the murder weapon. There were numerous prayer vigils, community dialogues and forums.

In June 2018, three years after the shootings, the Charleston City Council endorsed a resolution formally apologizing for the city’s role “supporting and fostering the institution of slavery.” After a lengthy debate, it passed by a narrow margin.

That same summer, plans for a $15 million Emanuel Nine Memorial, designed by Michael Arad, the architect behind the National September 11 Memorial in New York City, were unveiled as part of Mother Emanuel’s 200th anniversary celebration. With fundraising underway, the memorial, like the congregation’s grieving and recovery, remains a work in progress.

Healing takes time

Even before the shootings, Mother Emanuel faced challenges familiar to many older urban churches: dwindling and aging membership, impacts of gentrification, dated facilities in need of repair, according to Liz Alston, the congregation’s historian and a former trustee, who has been a member of Emanuel for more than 50 years.

Compound this with the sudden loss of the church’s pastor and a core of its leaders, followed by a rocky succession of three pastors in less than a year, and “many members started to have concerns,” Alston said. “So many members didn’t return [after the shootings], for a variety of reasons.”

On any given Sunday now, members at Mother Emanuel’s worship services may well be outnumbered by visitors. Some welcome this as an opportunity for ministry and outreach, while others long to return to normalcy, to reclaim the pews where generations of their family once sat.

And there have been messier rifts, including questions about financial transparency, lawsuits and an investigation by the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division regarding millions of dollars in donations. The investigation found no wrongdoing.

Two of the survivors, Felicia Sanders and Sheppard, felt abandoned by their church, reporting that pastoral leadership did not offer comfort or support following the shooting. Sheppard now worships at Mt. Zion AME, and Sanders is an elder at Second Presbyterian Church -- a congregation just a block behind Mother Emanuel.

Chris Singleton, who was an 18-year-old college freshman when his mother, Sharonda Coleman-Singleton, was killed in the shooting, is less critical of the church’s response.

“There were so many moving parts after the tragedy with no real focal point, because leadership changed frequently right after. Nobody could foresee how to handle all of that,” said Singleton, who now attends a more contemporary church. Though he found for a long time that just being in church made him anxious, he said he always felt welcomed and supported by Mother Emanuel.

Manning, now in his fourth year as leader of the congregation, acknowledges that it has been a difficult road, and one that he wasn’t fully prepared for. Helping a church recover from a massacre is not taught in divinity school.

“I do feel that now, after five years, Mother Emanuel is finding her footing,” Manning said. Before the pandemic, he believed that the congregation was getting to a place of real conversation. “I hosted chat sessions in which many shared that they were finally ready and able to talk about what happened,” he said.

Manning anticipated that healing would take time. “But I had no idea, early on, how much time it would take. Patience is one of the fruits of the Spirit,” he said.

“I’ve learned you have to be immensely patient when dealing with this type of hate crime, this type of violence in our sanctuary -- the violation of a space we believed to be safe. It takes time, peppered with trust,” he said.

Trauma-informed

After a similar massacre in 2018 devastated the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, Manning reached out to Tree of Life Rabbi Jeffrey Myers and the two became friends, sharing books and resources that had been helpful, and learning from their overlapping experiences.

“I had no idea what it meant as a pastor to be trauma-informed,” Manning said. “Now I understand.”

In part, it means extending grace and forgiveness to ministers who make mistakes, he said, “understanding that we were doing the best we possibly could at the time.”

What sorts of trauma should faith communities be prepared to address out of our most recent racist violence?

One of the biggest lessons Manning learned was to “listen not with your physical ear but with a spiritual ear.” This calls for validating parishioners regardless of where they find themselves in the grieving process.

Shelly Rambo, a Boston University School of Theology professor and expert in the field of trauma studies, feels that the term “trauma-attuned” is more appropriate for clergy dealing with issues like those faced by Manning and Myers.

A trauma-attuned church does the collective work “to hold the pain and then transform it,” Rambo said. Rather than a Pollyanna, “God’s going to make it all better” approach, “the work is to imagine a future that’s a continual witness to the harm done,” she said. “It is difficult hope work.”

That “hope work” entails rolling up your sleeves and engaging in activism, according to Manning.

“Just praying about it is not enough. You have to go further. You have to add your voice to the clarion call for social reform,” said Manning, who has been outspoken about gun control, among other issues. “Race relations are not where they need to be,” he said. “This pandemic shows the inequities.”

In addition to the pandemic, the current moment of heightened racial turmoil speaks to the long legacy of trauma, one that can be traced “back to chattel slavery, and the legacy of trauma of white supremacy in the country,” according to Serene Jones, the president of Union Theological Seminary and author of “Trauma and Grace.”

“Trauma is never just a moment; it lives in our bodies and in our unconscious actions and our communities over time,” Jones said. “That this fifth anniversary falls at the same time that [cities are] burning reminds us that as a society, we have to be committed to moving forward and to addressing the harms that traumatize communities.”

This broader social healing also requires patience and diligence, something the Black church knows well. “It’s ingrained in the DNA of the AME Church to be a light in the path of darkness,” Manning said. “Would I love for us to have gotten more things done? Yes. But it takes time, so you continue to push and press for change.”

Beyond forgiveness

Aftershocks of the shootings were felt in faith communities across the country. The night of the massacre, the Rev. William Lamar IV, the pastor of Metropolitan AME Church in Washington, D.C., began getting texts from colleagues; within hours, the bishop tasked him with planning a service of mourning for the next day in the nation’s capital.

“I preached about getting to the other side,” Lamar said. “And we’re not there yet.”

Even now, Lamar finds a narrative of forgiveness and grace inadequate. He feels that the tragedy must be understood in the context of a long history of oppression, including the fact that Mother Emanuel was destroyed before -- burned to the ground by white Charlestonians in 1822 because of its association with Vesey.

“African Methodists must confront the ugly reality of what America was, is and continues to be,” Lamar said. “I cannot forgive the Charleston shootings at Emanuel, nor what happened a couple of hundred years earlier, because the political and economic realities that created the oppression have not changed.

What are ways your church can be anti-racist and promote nonviolence?

“If we are serious, five years later, the ‘Kumbaya’ moment stops and we ask ourselves, ‘What produced a young man who would do this?’”

Lamar’s Charleston colleague the Rev. Kylon Middleton, the pastor of Mt. Zion AME Church, who was a close friend of Clementa Pinckney, agrees.

Middleton has spent the last five years reinvigorating Mt. Zion’s waning congregation and becoming an outspoken community leader and activist on social justice issues. But in terms of healing racial divides, some of Middleton’s time has been spent in a weekly Tuesday evening book study started by the Rev. Callie Walpole, the vicar at Mt. Zion’s backdoor neighbor, the predominantly white Grace Episcopal Church.

“Our congregations have been coexisting side by side, but we were siloed in our own bubbles,” Middleton said. “We were not paying close attention, sensitive attention, to those things that may force us to be more inclusive, empathetic and equitable.”

Honest and truthful

The book study began a month after the shootings, with Walpole’s longing for a deeper understanding of the cultural divides she had experienced growing up in Charleston.

“The Emanuel massacre stripped away the veneer. It seemed important that we at Grace start confronting these issues of race and injustice,” Walpole said.

The group first read Michelle Alexander’s “The New Jim Crow.” Walpole expected maybe five or six people around the table, but from the start, the room was full.

Walpole invited Middleton to attend, and eventually he did. Members of Mt. Zion joined as well. Today, 50 to 70 people from Grace and Mt. Zion consistently show up for the weekly study, now co-led by Middleton.

Brown, the Mt. Zion music director, is a book study regular.

“We’ve gotten close to each other,” Brown said. “We laugh; we talk. We knew we were going to get deep into it, but the stories we share are making a difference in people’s lives.” He found the discussion of “White Fragility” particularly revealing. “I hated the book, felt it was too much -- too strong -- for the whites who were there,” Brown said. “But we needed it. Good Lord, it was honest and truthful.”

How could churches in your community build relationships of trust and collaboration where they don’t exist or deepen them where they do?

Walpole and Middleton appreciate that such depth and honesty arises from relationships built over time. “It’s grueling work -- people have been showing up week after week for five years now, putting themselves out there,” Walpole said. And, she added, there have been direct results.

The book study has birthed related initiatives, including occasional communitywide Okra Soup Suppers featuring nationally known speakers such as former U.N. Ambassador Susan Rice. In 2017, some members organized a conference on criminal justice reform that drew more than 500 people.

“It’s hard to know what’s superficial and what’s deep transformation in terms of the long-term impact of Emanuel,” Walpole said. “True reconciliation is only possible with proper confrontation. Our hearts can be turned through encounters with others, and sometimes that’s a slow, slow process.”

As the Charleston community and Mother Emanuel mark this anniversary, the country is again gripped in despair and anger, even as the survivors and congregation continue the hard work of healing.

With trauma, Jones said, “the way forward is never the way of forgetting, never the way of nicety and Band-Aids, but the way of honesty and reckoning.”

Three things to know about trauma in a faith community

Shelly Rambo, a Boston University School of Theology professor and expert in the field of trauma studies, feels that “trauma-attuned” is a more appropriate term than “trauma-informed” for clergy dealing with issues like those faced at Mother Emanuel AME.

“The psychological language and toolkit is helpful, but the question becomes, ‘How do we integrate what we know about trauma into who we are as Christian communities?’” she said.

Rambo believes that a trauma-attuned faith leader needs to understand three things.

First, trauma is not something one gets over. It is never in the past but always part of the present. “A trauma-attuned congregation is continually aware of integrating whatever happened into the ongoing life of the congregation, into their present movement in the world,” she said.

Second, trauma lives in the physical body, not in a cognitive space. “So much of trauma can’t be spoken,” Rambo said, and physical space itself can trigger pain.

“I would want to know what a minister does to reorient church members to the space: How does it look different or the same? How have the rituals reoriented worshippers to the space?”

Preaching, which is a cognitive, word-based practice, has limits, she said. “Preachers need to learn how to understand silences as very productive.”

And finally, dealing with trauma takes work. A trauma-attuned church does the collective work “to hold the pain and then transform it,” Rambo said. Rather than a Pollyanna, “God’s going to make it all better” approach, “the work is to imagine a future that’s a continual witness to the harm done,” she said. “It is difficult hope work.”

The church already has organic resources and spiritual practices built into congregational life that can help facilitate this “hope work,” Rambo said, such as prayer, hospitality and group singing.

“But the current political layering of trauma with the reality that churches are no longer safe spaces, plus the fact that the anniversary of the Emanuel shootings coincides with a pandemic, might mean these traditional spiritual practices are restricted and thus need to be improvised and modified,” she said.

The Emanuel and Tree of Life massacres can no longer be isolated as one-off events but are part of the collective trauma, “the tone, the mood, in which all of life seems to be happening now,” Rambo said. This makes dealing with trauma even more difficult, especially for black churches.

“When there is not only an event of trauma but trauma as an ongoing condition of vulnerability within society, the fear and anxiety is compounded. It’s called ‘insidious trauma,’ for good reason,” Rambo said.

Questions to consider

Questions to consider

- How did the murders at Mother Emanuel affect the way you think about race relations in America?

- What sorts of trauma should faith communities be prepared to address out of our most recent racist violence?

- What are ways your church can be anti-racist and promote nonviolence?

- How could churches in your community build relationships of trust and collaboration where they don’t exist or deepen them where they do?