Jennifer Berry Hawes is a reporter’s reporter. She loves the pulse of the newsroom, the digging for sources and angles, the rush of meeting deadlines.

Throughout her 25-year journalism career, Hawes has written for daily newspapers. Since 1998 (minus a five-year child-rearing hiatus), she has been on staff at the Charleston, South Carolina, Post and Courier, one of the nation’s last independently owned dailies.

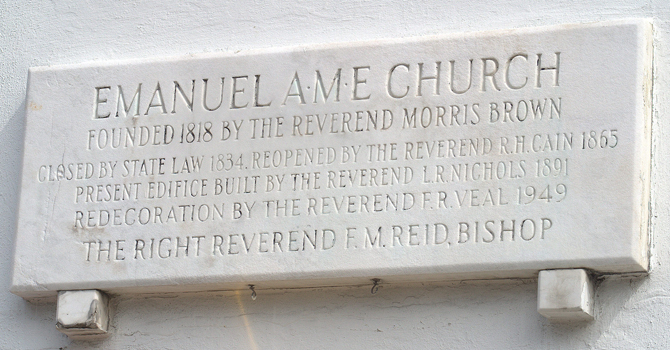

As a front-line reporter, Hawes was filing on-the-ground stories when her hometown witnessed one of the world’s biggest news events of the summer of 2015 -- the racist massacre of nine Bible study attendees at Charleston’s historic Emanuel AME Church.

As a front-line reporter, Hawes was filing on-the-ground stories when her hometown witnessed one of the world’s biggest news events of the summer of 2015 -- the racist massacre of nine Bible study attendees at Charleston’s historic Emanuel AME Church.

Hawes and her Post and Courier colleagues covered the shooting in all its grisly, tragic detail and then, long after the television cameras and cable news crews cleared out, the unfolding aftermath -- the criminal investigation, the church’s response, the community’s response, the survivors’ struggles.

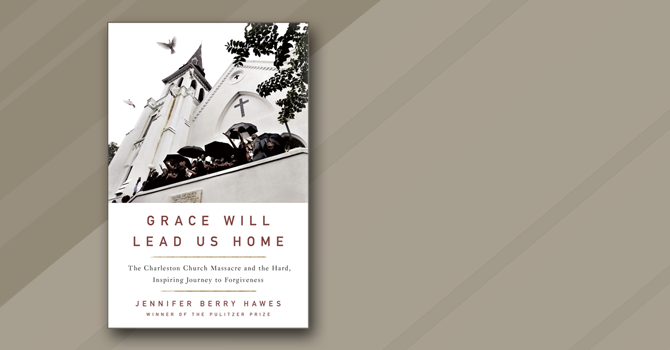

This summer, Hawes’ book about the shooting, “Grace Will Lead Us Home: The Charleston Church Massacre and the Hard, Inspiring Journey to Forgiveness” (St. Martin’s, 2019), was released in the week before the event’s fourth anniversary. Its timely theme is the hard work of healing for a community and for survivors.

Drawing on her decade of experience as a “faith and values” religion reporter, Hawes delves into the complexity of forgiveness for many of the survivors, as well as the challenges faced by, and in some cases caused by, church leadership in the wake of the shooting -- all set in the broader historical context of race and the black church in Charleston.

Hawes spoke with writer Stephanie Hunt about her experience writing the book and the lessons she hopes faith leaders can learn from it. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: How would you describe the dynamic of covering an unfolding story as it happens, then stepping back and writing about it from a more reflective angle?

Jennifer Berry Hawes: Reporting for a news story is very event driven. I’m covering something that is happening, which makes it newsworthy -- the distribution of the donations, for example, the survivors sharing their story for the first time, or family members speaking at events.

But the book is much more character driven, so I’m spending a lot of time with people, following their daily lives, their journeys, which is a very different exercise, and one that was stressful for me. I worried that I was often wasting their time, and my time, if the material didn’t end up being included.

But the book is much more character driven, so I’m spending a lot of time with people, following their daily lives, their journeys, which is a very different exercise, and one that was stressful for me. I worried that I was often wasting their time, and my time, if the material didn’t end up being included.

It was hard to winnow down, among the many characters and families involved in the story, those whom I would ultimately focus on. Ultimately, each character needs to have a narrative arc that resolves itself close to around the same time. I’d decided to make that time frame around Dylann Roof’s trial, because it provides a natural closure for people on a lot of levels.

But the reality of people’s lives isn’t so neat and tidy. Not everybody’s main hurdle was getting through the trial.

I ended up investing a lot of time really engaged with people who barely appear in the book, and I feel bad about that. But it was necessary. In the newsroom, we call it “killing your darlings,” letting go of the scenes you love that don’t serve the story. For the book, I was doing this times 300.

My goal was to bring all these threads, these narrative arcs, together. The individual stories we reported in the paper didn’t have the impact that I could create in the book. For example, reading a news story about concerns over the church’s handling of donations is one thing, versus seeing that controversy in the broader context of survivors feeling that they weren’t being ministered to and in the context of the pain they were all dealing with. Then you understand the enormity of the story all in one place.

F&L: Has that luxury of having deep time with people affected the way you approach your journalism and report other stories? In many ways, it sounds like pastoral care.

JBH: That’s an interesting analogy. You’re right. My job was to be present, be patient, and to observe -- to be there for no real purpose other than to be there. Sometimes it’s OK if you don’t get a quote. Relationship building is more important. Plus you never know what will happen when you are there, or as a result of being there.

F&L: The book’s subtitle echoes the theme of forgiveness that became the popular media spin on the Emanuel shooting. Has your understanding of forgiveness changed as a result of writing this?

JBH: I’ve learned that it’s much more complicated than just saying, “I forgive you.” Even the people who expressed forgiveness to Dylann Roof at the initial bond hearing will tell you that.

It was interesting for me to learn how important and ingrained the concept of forgiveness is, particularly in the black church. I don’t think I realized that, and I don’t think a lot of white people realize it, and the reasons for it. But even though that biblical teaching was so important to them, many family members did not forgive Dylann Roof, at least not right away.

For most of them, it required time and prayer and thought and healing and screaming and crying and being angry and all the things that go along with losing someone you love, especially in a sudden and violent way. And there are those who haven’t forgiven Roof to this day, and don’t intend to.

I think it’s important to see the families and survivors as individual people on individual journeys, not one homogeneous group. And it’s OK for the rest of us to have different reactions. Even if we as Christians are taught that forgiveness is our goal, we may process it differently.

It was also really interesting to me to think about forgiveness as an individual action versus a corporate action. That forgiving as a community is a lot different from me as an individual forgiving Dylann Roof. Collectively, I thought it was interesting when the city [of Charleston] issued its apology about slavery. It was a narrow council vote, with a lot of discussion about, “Well, I didn’t own slaves; I didn’t do anything wrong” versus a sense that we as a community can’t move forward in healing without first repenting of it.

Then there’s the question of whether forgiveness requires repentance. I had an interesting discussion with the wife of a rabbi at New Light Congregation, one of three congregations that worshipped at [Pittsburgh’s] Tree of Life synagogue [the site of a 2018 massacre], about this sense in the Jewish faith, which was my faith tradition until age 12, that forgiveness is based on someone atoning. But in the Christian faith, there’s more emphasis on forgiveness, even if it’s without repentance, for your own salvation. Not as much a person-to-person act but something between you and God.

Felicia Sanders’ husband did not forgive Roof; he saw him as a terribly evil person who did a terribly evil thing. But for Felicia, forgiveness was necessary so she didn’t go crazy with her own anger and sorrow -- so that hate didn’t corrode her soul and malice cost her her own salvation. So even within this one couple, you see the differences I was trying to explore. Forgiveness doesn’t wrap up neatly here, and that’s really the story I’m telling.

F&L: What lessons might other churches and religious leaders learn from this story?

JBH: A lot of lessons, I think. Sadly, this type of tragedy is more and more common, and the issues that Emanuel dealt with afterward are similar to what others might deal with, even if on a smaller scale.

One lesson is about the handling of donations, and the pain and distrust that results when they’re handled improperly. In Charleston, donations came in from around the world, and they generally went to two repositories. One was the city’s Hope Fund, and one was Emanuel -- people just sent items and cash-filled envelopes to the church.

The city handled its fund with transparency. They involved attorneys, including one who worked on the 9/11 fund, and accountants, and I heard very little criticism of how funds were handled or distributed by the city.

The church was not transparent. Even when they sent a lump-sum dispersal to the families, they included no explanation of how the amount was determined.

There are important lessons here, for churches or anyone: to have an objective third party handle money, and to have a clear accounting process, audited by someone not involved with the entity.

On the ministerial front, I think the biggest lesson comes from the failure of the Emanuel Church leaders to reach out to the survivors, even after Felicia [Sanders] wrote a letter to the interim pastor asking, “Please, could someone come provide me spiritual counseling?” And to just not show up?

To me, the lesson for a minister is to ask, “What is the most important thing for me to do in the midst of this chaos and hurt? What is the second most important thing?” And the answer is that the individuals need to be held and loved and provided spiritual support.

In fairness to Emanuel’s leaders, they didn’t have a guidebook, whereas now, unfortunately, we have a number of congregations who have been through this and are providing each other guidance and support. My hope that is if other houses of worship deal with anything similar to this, they can look to this story for guidance.

F&L: What about for the congregation?

JBH: I want to make it clear that when I’m talking about failures of the church leadership, I’m not talking about the Emanuel congregation. The congregation tried their best to fulfill a lot of different needs. The need and desire to be gracious hosts to visitors coming through, the need to be a voice regarding civil rights and racism, the need to deal with their own healing.

They really struggled to find the space to grieve and heal themselves while being inundated with so much chaos and attention. And they were doing all this having lost so many key people in the church. There were competing pressures on them, which was also true of the church leaders, who were trying to keep services going, lead tours, handle donations and media.

So while there are lessons to be learned in their shortcomings, there also needs to be an understanding of what they were up against. Again, one of the most important things I hope people in ministerial roles will think about is, What is the No. 1 function of a minister? What is the No. 1 function of the church? To me, it’s to be present and provide love and support.