Updated: In 2014, William G. Enright stepped down as executive director to become a senior fellow at the Lake Institute on Faith & Giving.

The Rev. William G. Enright of Indianapolis is a man of many gifts. Prophecy does not seem to be among them.

Here is someone who has spent the past 10 years and more engaging people of faith and faith communities in conversation about giving. But he laughs as he recalls a younger version of himself -- a newly minted associate at a Presbyterian church in Chicago in the 1960s informing a church secretary that he wasn’t interested in talking about money.

“I told her, ‘That’s not my issue. God’s given me a higher calling. I don’t have to be concerned about money.’ I look back and see where I am now …”

Where he is now -- and will be for a few more months -- is head of the Lake Institute on Faith & Giving, part of the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy at Indiana University. By the time he leaves the job this summer (he will stay on as a senior fellow), Enright will have spent more than a decade in one long discussion about what he calls “the big American taboo,” the intersection of religion and money.

Along the way, Enright has helped transform the conversation nationally about congregations, faith and giving. Bringing together experts in both pastoral ministry and academic research, Enright and the Lake Institute have fundamentally changed the way many local congregations think and talk about money.

Rather than being about internal church matters such as furnace repair and roofing estimates, “money talk” in those congregations is now about treasure -- treasure that can strengthen religious commitments and create health, love and care for others in a hurting world.

To Enright, it all begins with a right understanding of philanthropy.

“I find the word ‘philanthropy’ to be interesting,” Enright said. “It means ‘love for humanity,’ but I put a different spin on it. It’s love for humanity, but it’s also giving for the flourishing of humanity. How do we help people all around us to become better and address what their basic needs are?”

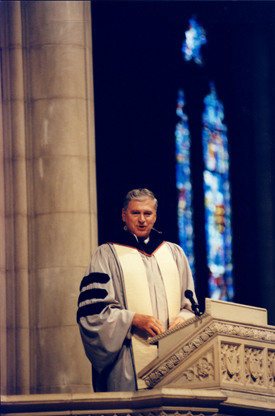

Enright didn’t develop that kind of thinking solely at the Lake Institute but brought much of it with him when he made the transition from the pulpit. From 1981 to 2004, he was pastor of Second Presbyterian Church, an imposing structure in a well-heeled neighborhood often described as “Indianapolis’ Protestant cathedral.”

Founded in 1838, the church was first pastored by the Rev. Henry Ward Beecher, the famous abolitionist preacher, and has long been an influential congregation of business and political leaders.

As pastor, Enright often broached the money-church taboo, teaching giving as fundamental to Christian joy and molding the congregation into one that “wraps its arms around the city,” said Craig Dykstra, a former parishioner.

“He was never shy about talking about the relationship between faith and money, but it rarely had much to do with pleas for funding the congregation,” said Dykstra, former senior vice president for religion at Lilly Endowment Inc. and now research professor of practical theology at Duke Divinity School and senior fellow at Leadership Education at Duke Divinity.

Generosity and the Christian life

Instead, Enright maintained that the relationship between faith and money was ultimately an issue of pastoral care, Dykstra said. To Enright, generosity and giving build on gratitude to God for God’s benevolence, which in turn prompts a sense of responsibility for the well-being of the city and the neighbor.

“To Bill, generosity and giving is the constituent dimension of the Christian life,” Dykstra said.

If so, then why have church people been so unwilling to talk about money? Where does the taboo come from?

Enright links it to the rise in the 20th century of the word “stewardship” as a euphemism for “fundraising” by people looking for a way to discuss money without actually using the word.

“Unfortunately, stewardship really has nothing to do with fundraising,” Enright said. “It’s about being a faithful manager of the resources and possessions with which we have been blessed and we have been given. We corrupted the word ‘stewardship,’ and it became a synonym for ‘fundraising.’”

As a result, at least in the Protestant tradition, the only time the pastor talked about money was in the annual stewardship sermon, which was part of the congregation’s annual fundraising effort.

The irony for Christians, Enright said, is that Jesus had more to say about money than any other subject.

“And that’s New Testament scholars who say that,” Enright said. “Faithful use of possessions and the kingdom of God are the two subjects that he spoke about most frequently. So the question that we ask is, Where did this get lost in the Christian tradition? Why did that get neglected when it was so central?”

As part of the broader Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, the Lake Institute works to answer those and other questions, helping clergy and other faith leaders think differently and talk openly and honestly about the relationship between faith and money.

“One of the principles we use in working with clergy is that you have to learn to talk about faith and giving with integrity,” Enright said. “Don’t dodge the lectionary, the text, when it deals with that, because it deals with that frequently. But separate your teaching on the faithful use of possessions from your fundraising.”

Established in 2003 -- with Enright becoming its first full-time director in 2004 -- the Lake Institute explores the relationship between faith and giving across various religious traditions, offering classes and programs for faith leaders, fundraisers and others. The institute’s mission is “to foster a greater understanding of the ways in which faith both inspires and informs giving by providing knowledge, education, and training.”

William G. Enright

Birth: December 5, 1935, Peoria, Ill.

Wife: Edie, married June 13, 1959

Children: Scott and Kirk

Grandchildren: Andy, Abbie, Nick, Dylan, Ella (ages 6-21)

Education: Wheaton College,

Fuller Theological Seminary,

McCormick Theological Seminary,

University of Edinburgh

Congregations: Roseland Presbyterian Church (Chicago) 1962-1965

Glen Ellyn Presbyterian Church (Illinois) 1968-1980

Second Presbyterian Church (Indianapolis) 1981-2004

The Rev. Tim Shapiro, the president of the Indianapolis Center for Congregations, says the Lake Institute under Enright has shifted the focus in church giving from stewardship, budgets and obligations to generosity, purpose and integrity.

“The Lake Institute programs provide leaders with the imagination to think in terms of possibility rather than scarcity, transparency rather than taboo, finances as expressions of faith practice, not a necessary evil,” Shapiro said. “Congregational leaders leave Lake Institute programs with specific action steps that they can begin to do immediately, steps that strengthen the link between faith and giving.”

Enright compared the institute’s courses and seminars to a trip to the doctor for the participants. But rather than providing a diagnosis and a prescription, the institute gives its “patients” the tools with which to make their own diagnoses.

Toward that end, the institute last year began offering an executive certificate in religious fundraising, an intensive training program for clergy leaders. Still in its pilot stages, the program is offered in partnership with various seminaries and colleges around the country. Two sessions were offered in 2013, and another seven are scheduled for 2014, all with waiting lists.

The program is only the latest in a portfolio of Lake Institute offerings, including seminars on faith and fundraising, creating congregational cultures of generosity, and spiritual values and philanthropic discernment.

If you’re looking for Enright’s legacy at the Lake Institute, these and other classes are a big part of it.

With its seminars, lectures, fellowships, books and reports, the Lake Institute today is a long way from the “blank sheet of paper” that Enright received from Robert Wood Lynn, the institute’s founding director, when he came on board in 2004.

Clearly, he was not intimidated by the move from the parish to the academy. After more than 40 years of ministry in Indianapolis, Chicago and Glen Ellyn, Ill., Enright welcomed the change.

“I always thought that’s where I would live,” Enright said of the academic world. “I would never have thought I’d spend my life in a parish.”

The opportunity at the Lake Institute, which came just as he was retiring from Second Presbyterian, was both providential and serendipitous, Enright said. It allowed him to be part of a place that serves as a bridge between the academy and the world.

Kid in a candy store

“I told my wife, Edie, that sometimes I just feel like a kid in a candy store,” Enright said. “I get to hang around all these bright people and learn from them.”

But why study religious giving?

Because it’s the biggest slice of the philanthropic pie, Enright said. According to research at the Lilly School, 72 percent of household giving in terms of dollars goes to religion -related institutions -- congregations, of course, but also theological institutions and faith-based charities. And therein lies a lesson for the larger philanthropic world Enright describes as “skittish” about religion.

“If you can understand the religious background from which a person is coming, you can engage them in conversation,” Enright said. “In philanthropy, you’re helping people find a calling.”

Of course, those conversations about calling, about philanthropy and faith, money and church, must always factor in the national economy, whether good or bad. Lilly School data show that while religious giving has increased 1.5 percent every year since 1970, it has failed to keep pace with inflation averaging 3.4 percent each year. The gap becomes increasingly significant over time, putting many congregations in what Enright calls “survival mode.”

But even in a tough economy, church leaders can find ways to help people make the connection between giving and faith, Enright said. He has seen and heard stories about congregations responding to the Great Recession by finding ways to continue their mission, including clergy taking salary cuts.

“The last thing congregations wanted to cut were these outreach programs serving the needy around them,” he said.

the Associate Director of the Lake Institute

After a sojourn at the University of Edinburgh for his Ph.D., he found himself at a church in suburban Glen Ellyn, Ill., where he began a program to build a bridge with an African-American parish in the inner city. It took three years for the effort to take hold, but in the process, Enright came to see building bridges as part of his calling.

During his years at Second Presbyterian, Enright forged critical ecumenical and interfaith relationships that paved the way for his inclusive work on faith and giving at the Lake Institute. Under Enright’s leadership, members of his church and Indianapolis Hebrew Congregation gathered in one another’s homes for intimate interfaith conversations. Out of that grew shared Thanksgiving observances.

Similarly, Enright joined Bishop T. Garrett Benjamin, then pastor of Light of the World Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), to lead congregations across Indianapolis in Celebration of Hope, an annual citywide worship service to unite Christians of all races and denominations.

History of ecumenism

Given Enright’s history of ecumenism, it is not surprising that the institute’s efforts reflect diversity. The annual Thomas H. Lake Lecture has featured national leaders in Jewish, Christian and Muslim philanthropy, including Ingrid Mattson, the director of and a professor at Hartford Seminary’s Macdonald Center for the Study of Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations. The institute’s visiting scholars program has included Eboo Patel, the founder of Interfaith Youth Core (IFYC), an international organization that enables young people to bridge religious traditions to serve humanity, and Ruth Messinger, the president of American Jewish World Service.

“He knows how to work with other people and integrate what he’s doing with the work of other people,” said Eugene Tempel, the dean of the Lilly School and Enright’s boss. “He knows how to focus on teamwork, how to build teams inside an organization. He’s truly what people in sociology would call a boundary spanner, able to move from one camp to another, able to connect people from different camps very easily. Those are some of his real strengths.”

And how will Enright apply those strengths now? What will he do after stepping down as the institute's director?

Nobody, especially Enright, seems particularly worried. Tempel suggested a role in fundraising for the Lilly School, and Enright and a colleague have been working on a proposal for a course, “Calling and Philanthropy.” Other than that, Enright has the attitude of a man awaiting his Next Major Opportunity.

It is in keeping with a principle he gleaned from Herbert Butterfield’s “Christianity and History” (1950), a book that has influenced him enormously.

“He said, ‘Hold to Christ, and as for all the rest, be totally uncommitted.’ And that’s been a mantra for me,” Enright said. “To keep an open mind; to everything else remain uncommitted. And you have to build bridges.”

Questions to consider

Questions to consider:

- What difference would it make if your congregation or institution considered giving not a question of stewardship, budgets and obligations but one of generosity, purpose and integrity?

- Who are your organization’s most generous donors? Why do they give? What is the link between their generosity and their faith and vocation? How did they learn to nurture that connection?

- Whose vocation are you nurturing? How is giving part of that nurturing?

- What are the trends for giving in your congregation or institution? What are your giving opportunities and challenges? Who will be donors in the future?