Our attempts to relate to other churches are often haphazard. Except for an occasional “pulpit exchange” or the joining of hands for a local good cause, many churches leave it up to the individual members to work out when and how people engage with another community of Christians.

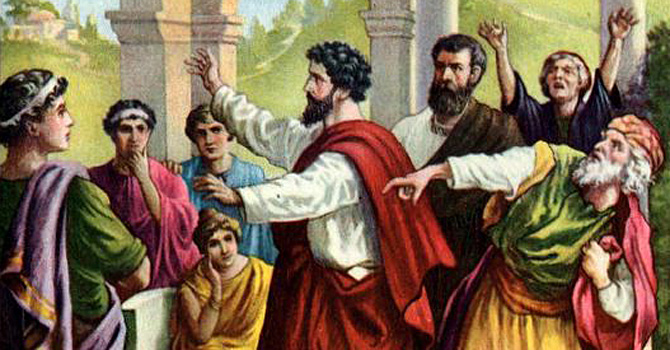

It therefore can be quite surprising to discover that the early church was strategic. As the book of Acts shows in detail, the early Christians believed that it was necessary to create a tightly interlocking web of communities. The earliest missionaries would doubtless have taken all comers, but they focused on establishing communities in major urban centers such as Ephesus, Corinth and Rome or in cities that were geographically well-positioned for travel and trade (for example, Thessalonica, Philippi, Antioch). Establishing house churches in these locations allowed easy communication and movement between the various communities.

Because of the speed and ease of our own communication, we often pass much too quickly by the remarkable fact that the churches in Acts were in regular communication with one another. Frequently this connection between the churches is seen in the pauses between the main vignettes of the story, such as when Luke notes that after Paul and Barnabas established a church in Derbe, “they returned to Lystra and to Iconium and to Antioch, strengthening the souls of the disciples …” (14:21-22 RSV). But the importance of networked communication can also be made more explicit, as it is, for instance, in relation to the all-important letter that emerged from the Jerusalem Council.

In a day when there was no form of communication other than the delivery of messages by physical presence (whether oral or written, someone had to take the message to where it needed to be), and when all travel on land was by foot or beast, the leaders in Jerusalem were nevertheless able to assume that their decision about the Gentiles and the Jewish law would reach the tiny Christian communities scattered around the Mediterranean rim. This assumption was grounded in the practice the churches had long observed -- the sending of key Christian leaders from community to community.

In this case, in addition to Paul and Barnabas, the “apostles and elders” in Jerusalem chose Judas and Silas to go to Antioch with their message (15:24-27). After delivering the message there, Judas and Silas were “sent off in peace” to those who had originally sent them. In returning to Jerusalem, these two men were strengthening the line of connection between the Christians in Antioch with those in the Jerusalem community. Paul and Barnabas then decided that they should, in turn, “go back and visit the brothers and sisters in every city where we proclaimed the word of the Lord” (15:36).

That they could not agree on whom to take is not as important as the fact that even after their disagreement, both Paul and Barnabas went to visit Christian communities and take the news (15:36-41). Barnabas sailed to the Christians on Cyprus (cf. 13:4-12), and Paul “went through Syria and Cilicia, strengthening the churches” (15:41). In short, without the networked life that was early Christianity, the effectiveness of the Jerusalem Council’s decision in the life of the Christian churches would not have been possible.

It is no accident, of course, that the words “community” and “communicate” derive from the same Latin root ( communicare). Community without communication is a contradiction. The early Christians may not have formulated it in just this way, but they knew its truth. By developing and maintaining the links between their geographically separate communities, they displayed in a very practical sense their understanding that being one church required constant communication.

Indeed, establishing the language of “brother and sister” as a serious option for how to read other people -- Christians across the Mediterranean, regardless of other differences -- is literally inconceivable without the networks needed to sustain a common sense of identity and purpose. Networking in a serious sense does not automatically lead to a common sense of identity and purpose, but without networking it is hard to imagine that a unified identity and purpose could ever be maintained. To put it simply: as the book of Acts shows, the early church found networking to be indispensable for their thriving in the deepest sense -- their ability to be Christians.

This is part of a series. Learn more about the concept of Thriving Communities »