As we move into a new stage of the pandemic -- one of cautious planning and hope tempered with the scars of protracted crisis and communal grief -- we have an opportunity to rethink our relationships with work, community, spaces and more.

Think pieces about what we’ve learned and where we are going clutter our news feeds. Even as a generally reflective person, I find the onslaught unnerving.

I have come to recognize this sense of being overwhelmed as rooted in my yearning for a critical evaluation -- within myself and with my communities -- of how we think about, move about and live within time. Specifically, I need to consider the way my relationship with time is a function of the values of white supremacy.

For many months, time has felt like a pile of pudding on a hot sidewalk -- ill-defined, shape-shifting mush. The difference between one day and another has blurred, marked most clearly by how many hours we sat in front of Zoom.

Many of us have moved through this time in a hazed panic. The multiple and compounding emergencies of the COVID-19 pandemic, white Americans’ racial awakening, economic instability, and the resultant mental and spiritual health crises have conditioned us into unsustainable postures of reactionary urgency.

In the words of my colleague Wanda, “A person can’t think critically about what’s important if everything is vaguely urgent.”

Returning to in-person work, for me, cannot be simply about vaccinations, air hygiene and testing protocols. We must undertake a radical evaluation of the way that white-dominant work culture stands in opposition to the creation of transformative communities.

In my work, this is less about revisiting hiring strategies or cultural competency training and far more about intentionally reorienting my relationship to and expectations of time.

As a young church worker, I was part of a staff that employed a consultant to evaluate our polity and staff function. During one of our team sessions with the consultant, we were asked to complete a weekly calendar, blocking off what chunks of time we dedicated to different aspects of our work and lives. These neat chronological blocks assumed that there were functional and enforceable boundaries between tasks, relationships and vocations.

I don’t remember the purpose of this activity, but it is a model of time management and life “balance” that has stuck with me. It is a model of time management that the pandemic ate for breakfast. And it is a model of time management that is embedded in a culturally informed notion of time.

In most work cultures in the United States, we reward well-managed chronological time. We consider workers who are able to focus on their work and complete their tasks efficiently and in a linear sequence “good.” Disruptions are not to be tolerated. Meetings are often maligned as a “waste of time.” Precise schedules are highly valued. Time is viewed as a limited commodity.

Some have named this kind of relationship to time “monochronic” -- experienced in a one-thing-at-a-time way.

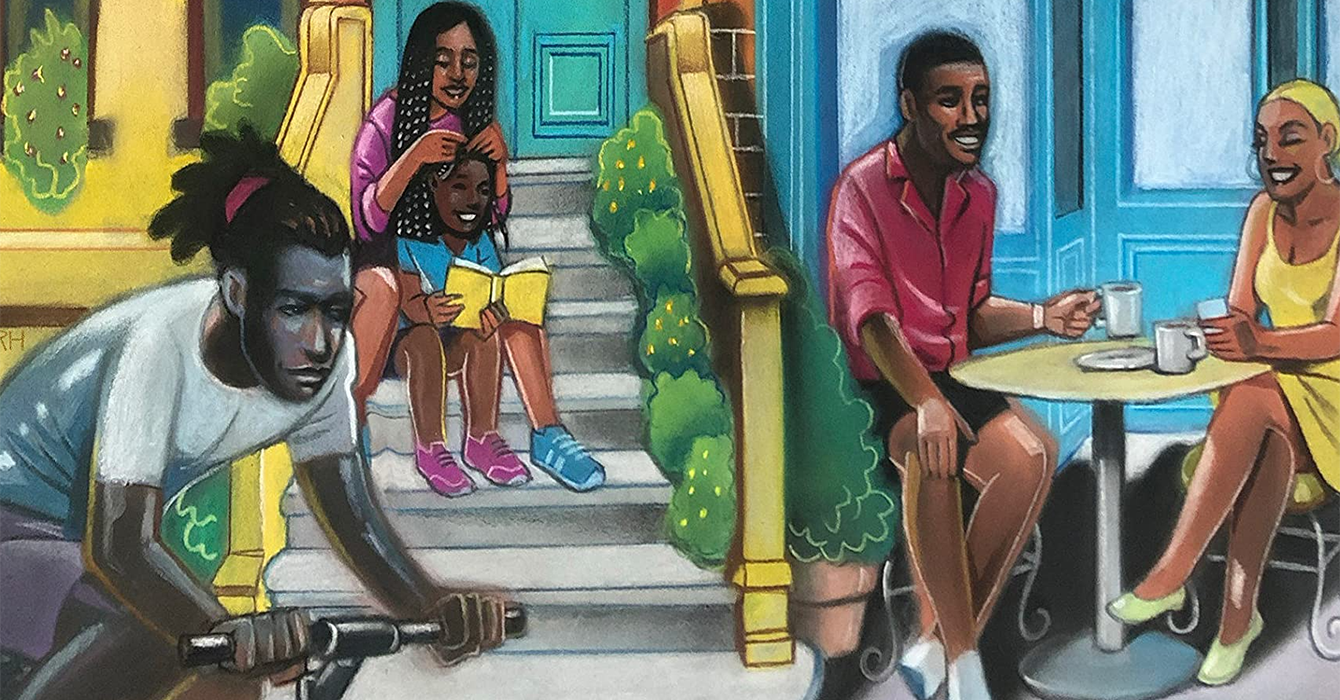

On the opposite end of the spectrum is a “polychronic” experience. Polychronic cultures often blend multiple tasks, relationships and responsibilities into one moment. Time has fewer boundaries and is less segmented. The start time and length of a meeting is less important than the relationship with the people in the meeting. Timely completion of tasks is not inherently valued; the driving force is the relationship with the task and collaborators.

A map of cultures that are predominantly monochronic fits neatly atop a map of some countries and regions that have historically colonized others: Western and Northern Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia and Japan. It’s not hard to see how forcing monochronic sensibilities on diverse workplace communities is a reiteration of colonialism.

Monochronic work culture in the United States is enmeshed in white culture and is used to dismiss nonwhite workers as lazy, incompetent and disrespectful.

If you have committed to dismantling white supremacy and racism in yourself, in your work and home communities, and in the United States, I commend to you the evaluation of your relationship with time and tasks.

I do not claim completion of this work, but I can share some practices and principles I am integrating to dismantle the veneration of white cultural norms in myself and in my work:

- Reorienting away from an urgency-based mentality with ASAP deadlines to a collaborative decision-making process in which all team members create a reasonable timeline for the work according to the other demands on their lives and energies.

- Reframing interruptions and distractions as part of being a complex person responding to the multiple callings in my life; likewise, embracing the multivocational reality of everyone’s life.

- Encouraging rest, and knowing when what has been accomplished is good enough.

- Creating meetings that are conversations, not a run-through of talking points.

- Communicating my capacities and abilities to meet others’ expectations; building in space for others when they need more resources or time.

- Honoring when others say "no" because my healthy relationship with time requires respect for their healthy relationship with time.