The reckoning came five years ago when Park Street United Methodist Church needed a new roof for its sanctuary and education building.

The bill came to $38,000, which was a stretch for the church. But then five months later, another building the church had used as a Boy Scout meeting place also needed a new roof. The cost? $34,000.

The two roof replacements put a real strain on the 99-year-old church and wiped out whatever funds the congregation had set aside for capital improvements.

“That began the conversation -- ‘If something big goes wrong, how do we pay for it?’” said the Rev. J. David Hiatt, the pastor of the church located in the growing community of Belmont, North Carolina, about 15 miles west of Charlotte. “You can’t patch things forever.”

The church, which has about 275 members and a Sunday worship attendance of 150, did have one valuable asset: a campus of 4.5 acres on a central street corner just a few blocks from downtown Belmont’s commercial heart.

In 2017, the congregation began to consult with a community development corporation set up to help United Methodist churches in the Carolinas develop or repurpose church-owned real estate.

Formed with support from The Duke Endowment, Wesley CDC guides churches to think strategically about how to maximize their property assets to ensure that they remain financially stable and strong at a time of rapid social and cultural change.

Recognizing that traditional mainline Protestant churches are facing a long and slow decline, with birth rates and baptisms dropping and member rolls graying, leaders of Wesley Community Development -- experts in finance, real estate, construction, community development and ministry -- help churches learn how to survive and thrive by taking stock of their assets and putting them to use as resources for their communities.

“We talk to churches about how to use their physical assets to help engage the community and be more a part of it,” said Joel Gilland, the president of Wesley CDC.

Focus on what you have, not what you need

Churches helped by the CDC’s design and contracting services have gone on to retrofit their campuses to start preschool and after-school programs, build affordable housing, lease their commercial kitchens, carve out co-working spaces, rent space to nonprofits, plant community gardens, open recreational facilities and set up health ministries, among other things.

Wesley CDC now manages all the unused properties in the United Methodist Church’s Western North Carolina Conference and is responsible for their ultimate maintenance or sale. It also manages the conference’s headquarters and has mapped all 2,400 parcels of real estate in the conference -- a total of nearly 7,600 acres.

“When a church is closed by action of the annual conference, Wesley helps us do an analysis of whether to put it up for sale or put it into some other use,” said R. Mark King, the conference treasurer. “They are in a great position to be fiduciary manager of the conference’s property.”

Who in your church decides how and when buildings and property are utilized? What priorities shape those decisions?

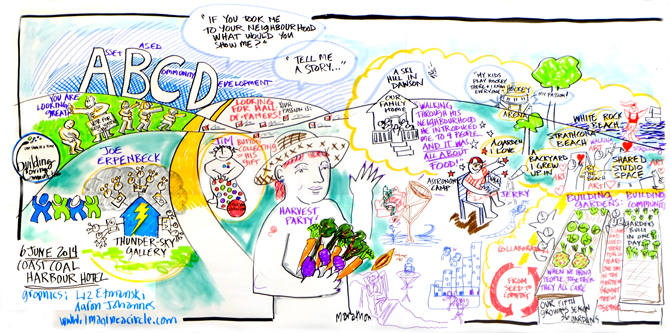

The work of Wesley CDC is driven by the idea that churches should focus on what they have rather than what they need, an approach sometimes referred to as asset-based community development, or ABCD.

But the key insight at the heart of the CDC’s work lies with the teachings of John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, who believed that community engagement is vital to achieving a church’s mission. Churches disconnected from the communities in which they’re located are unlikely to thrive, Gilland said.

At the heart of the CDC’s work is a two-day program called Seeds of Change. Churches that apply and are accepted send the pastor and two laypeople to brainstorm better ways of using the assets they have to engage with their community.

“We talk about how to discover the community’s needs, assets and dreams,” said the Rev. Karen Easter Bayne, the vice president of church engagement at Wesley CDC and coordinator of its Seeds of Change seminar. “Then we focus on the mission of the church and how it sees itself living out that vision along with the community around it.”

What are the needs in the community near your property? Could assets such as the parking lot, yard and buildings be used in new ways to address those needs?

Sixty churches have participated in the Seeds of Change program so far. Another nine will participate in February.

The need for the program is great. The Western North Carolina Conference of the United Methodist Church estimates that 40-50 of its churches will close each year over the next five years -- a total of 20%-25% of its 1,055 congregations. (Each church has a clause in its deed stipulating that if the church closes, the property reverts to the conference’s board of trustees, who decide on its disposition.)

Other churches in the conference are still viable but have aging facilities and the prospect of costly repairs that may strain them to the breaking point. Park Street is among them. Its leaders, however, are convinced that there is another way.

“The Belmont community is growing, and we’re in a prime location,” said Hiatt. “We could use our real estate more effectively to fund the ministry we want to do.”

The right kind of space

Shortly after participating in the Seeds of Change program, the Park Street team began to rethink the church’s empty spaces.

Having been asked during the Seeds of Change program to evaluate how often their church facilities are used on a weekly basis, they came up against a stark reality. Its four buildings were used on average only 10%-15% of the time each week.

How much are your buildings being used?

And that’s par for the course.

“We have confirmed the average church, no matter their size, whether they’re urban or rural, or black or white, the percentage of hours people use their church facility is 12%-14%,” said Easter Bayne. “That helps them say, ‘We need to get real. We’re supposed to be good stewards of all we have, and we’re not.’”

To make the best use of the two-day program, Easter Bayne visits the participating church in advance, talking to the pastor, snapping photos of the property and getting a good understanding of the challenges and opportunities available to the congregation.

The first day of the Seeds of Change program begins with the question, “Why do we need to change?” Easter Bayne presents a global view of shifts happening in churches nationwide and in the culture. Then the church members begin to discuss their mission and how they see themselves living out that mission in the community around them.

On the second day of the program, things get granular. Church members consider the steps they need to take and the resources available to them.

What is the relationship between your congregation and the organizations that use your building? Are the missions of those organizations connected to your priorities for ministry?

“We want to make sure by the time they leave they have some ideas in mind about next steps,” Easter Bayne said.

Park Street members who completed the Seeds of Change program came home with a commitment to lease some of the church’s unused space. A Christian counseling group took over the third floor of the education building. A violin teacher rented a few classrooms on the first floor. And a taekwondo instructor leased the Boy Scout building, turning it into a dojo, or martial arts training studio.

The lease income from those groups, along with another home on the property, brought in about $20,000 last year -- money the church is setting aside for capital improvements.

Park Street is now working with Wesley CDC on a larger plan that includes building some townhomes, senior housing apartments, and commercial and retail space on the edge of its property. The idea is to partner with a developer who would build the homes and retail spaces and split the income from rentals with the church.

Belmont is a fast-growing community increasingly attractive to young couples and elderly people who may be priced out of the more affluent Charlotte real estate market.

Income from housing and retail would allow the church to tear down the education building and refurbish the 1957 sanctuary to accommodate a more contemporary worship style.

Updating the sanctuary’s electrical system -- which is not currently grounded -- would allow the church band, with its amplifiers and electrical instruments, to play there. And replacing the fixed pews with moveable chairs would allow the space to be used beyond the Sunday service for a variety of community events, such as concerts, lectures or plays.

“What we’re doing here is about survival,” said Craig McHugh, who chairs Park Street’s long-range plan and visioning team. “If we don’t do anything, I know what’s going to happen. We all do,” he said. “You can’t keep doing the same things over and over again and expect something different to happen. I believe this long-range plan has energized the folks. We’re excited.”

Wesley CDC leaders are expected to present the church with a final blueprint for the design and development of the Park Street campus in a month or two. The nonprofit has already proved its design skills elsewhere:

- In east Charlotte, Central United Methodist Church renovated two classrooms to start a multicultural dual-language preschool for children whose parents come from a dozen different countries. The Children of the World Learning Center, now in its second year, has enrolled 20 children and has begun paying rent to the church.

- Charlotte’s First United Methodist Church renovated its facility so it could lease unused space to the city’s burgeoning performing arts groups. As a result, it is now cultivating relationships with the local arts community in ways that are mutually beneficial.

- Thirty-five miles north of Charlotte, Motts Grove United Methodist Church has begun to rethink how to use the campground it owns next to the church. The 6-acre plot was being used only two weeks a year. Recently, it has become a venue for outdoor concerts, a flea market and a Christmas drama.

- Another suburban Charlotte church, Harrisburg United Methodist, is planning to build a youth facility and add handicapped-accessible showers and bathrooms to its fellowship hall so it can serve as a Red Cross shelter.

The Rev. Toni Ruth Smith, co-pastor of Harrisburg United Methodist, said the fast-growing church of about 400 members had considered expanding the sanctuary 20 years ago. That plan failed to win support from members. From today’s perspective, Smith said she thanks God that the campaign failed.

“The old mindset was, ‘If you build it, they will come,’” she said. “Wesley [CDC] told us, ‘You have to think of your assets as a whole, and you have to think, What is the ministry you want to do? And what will help you do that better?’ I don’t think I’d have come up with those questions or had the resources to answer them without Wesley.”

Building community

On a Wednesday morning last month, Hiatt sat down at his Park Street desk to write thank-you cards to last year’s top donors. As he scanned the list, he noticed that most of those donors had something in common: they were all elderly.

“It won’t be five or 10 years before those top givers are no longer alive,” he thought.

If in past years Hiatt might have resorted to the old way of thinking -- cut back on missions and ministry to pay for maintenance and upkeep -- he now felt buoyed that the Wesley message offered a way forward.

Of course, there are no guarantees that Wesley CDC can bring all struggling churches back to life.

The group won’t work with churches that are on a path toward closing, because by that point it may be too late to change direction.

And occasionally, it will recommend that still-viable churches with unworkable properties sell and move.

Christ United Methodist Church in High Point, North Carolina, for example, had an older urban campus that presented many costly challenges. Last year, at Wesley’s recommendation, the church sold its property to High Point University for $2.75 million.

The congregation, with about 200 active members, is now sharing space with another church but is looking to buy a smaller, more flexible space that would better suit the congregation long-term.

What can you and the groups who use your building do together to serve the community that no one organization could do alone?

The key for all of Wesley’s work is the notion that churches can no longer afford to be isolated, inward-facing islands. They have to think about their roles in the larger communities they serve.

Park Street has gotten the message. Recently, it has expanded its work with two county health departments by hosting a senior prom for people who attend an adult day care and providing space for prediabetes prevention classes. It envisions doing more in the future.

“Our mission is growing discipleship through relationships,” said Hiatt. “We don’t want to be a church that exists in Belmont but a church that exists for Belmont, so we help the whole community move forward.”

Questions to consider

Questions to consider

- Who in your church decides how and when buildings and property are utilized? What priorities shape those decisions?

- What are the needs in the community near your property? Could assets such as the parking lot, yard and buildings be used in new ways to address those needs?

- Wesley CDC says the average church facility is used just 12%-14% of the hours in a week. How much are your buildings being used?

- What is the relationship between your congregation and the organizations that use your building? Are the missions of those organizations connected to your priorities for ministry?

- What can you and the groups who use your building do together to serve the community that no one organization could do alone?