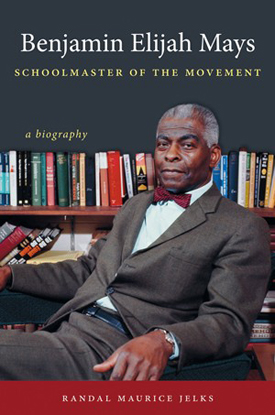

The late Benjamin Mays, the president of Morehouse College from 1940 to 1967, is often remembered today -- if at all -- as a mentor to Martin Luther King Jr., but Mays was in fact “somebody to be known in and of himself,” says Mays biographer Randal Jelks.

“If he had been president of Harvard with the list of illustrious students he had, we’d have more books about him and his leadership,” said Jelks, an associate professor of American studies at the University of Kansas and the author of “Benjamin Elijah Mays, Schoolmaster of the Movement: A Biography.”

A college president and Baptist minister, Mays was a key intellectual figure who bridged the academy and the church and helped lay the groundwork for the civil rights movement.

“Everywhere in the civil rights movement in the South in the 1930s, ’40s, ’50s, Mays’ name came up, but there was no full accounting of his life, so I wanted to do that,” Jelks said.

At Kansas, Jelks also holds a joint appointment in African and African-American studies. His scholarly interests include African-American religious history, black urban political history, black trans-Atlantic religious history and the history of American social movements.

At Kansas, Jelks also holds a joint appointment in African and African-American studies. His scholarly interests include African-American religious history, black urban political history, black trans-Atlantic religious history and the history of American social movements.

Jelks spoke with Faith & Leadership while at Duke Divinity School recently to deliver the 2014 MLK Lecture. The following is an edited transcript.

Q: Tell us about Benjamin Mays. Who was he, and why was he important?

That’s always the question I get. Benjamin Mays was the president of Morehouse College in Atlanta from 1940 to 1967. His reputation was cemented because Martin Luther King Jr. called him his spiritual and intellectual father. That’s high praise, but Mays was somebody to be known in and of himself, and not simply through one of his best-known students.

It wasn’t only King who praised him. Marian Wright Edelman, who started the Children’s Defense Fund, called Mays a mentor. Vernon Jordan, Julian Bond -- the list goes on and on. So I wanted to write Mays back into the history.

He was a theologian, with an M.A. in New Testament and a Ph.D. in theology from the University of Chicago, and an important leader. He led the Howard University School of Religion -- now the Howard University Divinity School.

Everywhere in the civil rights movement in the South in the 1930s, ’40s, ’50s, Mays’ name came up, but there was no full accounting of his life, so I wanted to do that. He was a key intellectual figure who bridged the academy and the church, a college president and a Baptist minister. I wanted to get his story back out there.

Q: Mays is credited by many with laying the intellectual and theological groundwork for the black church’s role in the civil rights movement.

That’s right. He went to India and met and interviewed Gandhi in 1936 and came back and wrote about his encounter. He talked with Gandhi about what a nonviolent social movement looks like and how it should take place.

Martin King was 15 when he came to Morehouse. The war was beginning to affect enrollment, and Mays, at an all-men’s college, used early admissions to find talented teenagers to enroll.

King and other students were often invited to Mays’ house to sit at table when dignitaries were visiting. The students had to learn about the visitor beforehand and were expected by Dr. and Mrs. Mays to ask questions. The great civil rights activist Dorothy Height remembers meeting Martin King at 15 sitting at the Mayses’ dining room table. This was not peculiar to King. Many other students tell you the same.

The Mayses didn’t have children, so they had two or three young men, lower-income students who needed help to go to college, who stayed at their house and worked as houseboys -- cleaning and polishing -- and went to class. And then they were expected to sit at dinner.

One guy, who later earned a Ph.D., told me it was like having another set of parents. They took an active interest in these young men.

That kind of mentoring by a college president is rare today, but in Mays’ case, every Tuesday when he was in town he would speak to the students. He would give them a sermon, a homily, something to challenge their lives. It was real moral formation for them, and he came from a pretty humble background himself.

He was a tenant farmer from near Ninety Six, South Carolina, born in 1894.

For a man or a woman to make that journey from near Ninety Six, a little town called Epworth, up to Maine to Bates College and from Bates College to the University of Chicago is quite a feat.

Q: How did he get to Bates College?

He was 26 when he graduated from Bates. He didn’t graduate high school until nearly 22.

He was always fighting his father, because his father wanted him to work the land. He would say, “You’ve got an eighth-grade education. What more do you need? You can read the Bible and you can farm.”

It’s a good old Southern story: “You can read and you can farm -- what the heck do you need to go to school for?”

He was the youngest, and he was always resisting, so he made his way to South Carolina State College, now University, where the black high school was. To pay the fees, he cleaned houses and did all kinds of things and finally got a job as a Pullman porter in the summer, which really allowed him to make the wages that freed him up to defy his father and go to school.

It was true throughout the region. The tenant farmer’s children were obligated until they were 21. A father could send the sheriff to get his son and tell him, “You’ve got to come back and farm.” That was the law. Mays always worried that his father would do that, but his mother actually took the plow and started doing his chores to allow him to go to school.

Q: Mays lived from 1894 to 1984, and was president of Morehouse from 1940 to 1967. Those are both incredible periods in U.S. history and in African-American history. Speak to that some.

Think about it. He’s a point person who everybody contacts when they come to Atlanta. Of the black college presidents around Atlanta, he’s the most loved, because he told students that they were right to protest injustices.

One guy I interviewed for the book told me Dr. Mays would tell you to go out and protest but that you better be back home in time for exams.

He believed in rigor. He believed in academic excellence. The man I interviewed said he was always trying to figure out how to do the social justice Dr. Mays commanded them to do and also keep the academic rigor.

Mays expected his students could do both.

Mays should be known. If he had been president of Harvard with the list of illustrious students he had, we’d have more books about him and his leadership.

Q: You’re at the Divinity School to give the 2014 MLK Lecture, entitled “Benjamin Mays and Martin Luther King Jr.: The Spiritual and Social Justice Imperative to Re-Think Everyday Violence.” What’s that about?

Mays advocated for nonviolence, and King built on that legacy. But in some ways, they fell short.

Nonviolence was a big social force to fight discrimination, but we’ve learned from scholars and woman activists that the domestic sphere of life is just as important. The ways we talk about civic freedoms intersect with a kind of local violence.

I’ve been thinking and reflecting about the level of shootings in Chicago over the last couple of years, and the level of violence when people feel incapacitated. I look at this historically and I try to identify the past, how the struggle has been named, but also what we can now learn from that and be creative about ways of stopping other kinds of damaging effects to people’s lives.

We have a contentious debate in America about gun violence and whether guns cause deaths. But it is certain that we have a high level of violence. There are just as many guns in Switzerland as the United States, but the level of gun violence [there] is much lower.

I’m trying to think how we can use the past creatively in addressing new issues and new ways of talking about violence. If guns aren’t the problem, what is it about our culture that makes it so violent?

It took us a long time to think about domestic violence, of one spouse to another, one partner to another. In the same way, nobody needs to live in fear of walking down the street or feeling like, “I’m going to the store and I may not come back.”

In his autobiography, Mays talks a lot about domestic violence. He had a brother who was murdered, shot by a cousin over a property dispute. It was very traumatic for Mays.

And like in any number of families, his father drank too much. Mays kept close counsel, but he said his father was “scary” and that his home was not a happy or pleasant place.

This interest also comes out of my experience. I served seven years pastoring an inner-city church. I loved every minute of it, but often you don’t have time to think.

So I’m always thinking about the ways we can enrich and reshape people’s lives. I’m not just interested in violence as a scholarly question. I’m curious about the ways that we’ve thought about violence, particularly Christians. Do we pick up the sword or the cross? Which one is it? There’s always tension.

But we ought to at least be clear about what our assumptions are and be aware of what we’re saying and what the gospel says, and at least have our ground being set.

It is important to think about theology not as an abstraction but as a way of giving core values to folks at the everyday level. That’s what churches do when they’re at their best.

Q: Given Mays’ work in helping to shape the civil rights movement, how well has the church honored that legacy?

One of my critiques of Mays and others is that they didn’t spend enough time thinking about the way people actually live and perform their religion.

They had these big notions and ideas. It was about a social movement, a necessary social movement. But what are the key components of those doctrines for what the pastor deals with every day -- from marriage counseling to the funeral to people expecting some word on how to make it through every day?

America has changed. I argue in the book that into the late 1960s -- well, still today -- it was being shaped largely by not a Protestant class but Protestantism.

Look, Robert McNamara was a good Presbyterian. He went to the First Presbyterian Church of Ann Arbor. Kennan, Dulles, all of these were good men. They all were church people, but they undermined the moral authority in their public pronouncements in the way they ran the country. Pretty soon people lost faith in church and in churches, and churches also lost faith in what their role was.

Many churches abandoned the core city and moved to the suburbs, sold older buildings to new congregations.

Now you have a revival of all these core cities and very few downtown churches left to meet any new people who care about the church. So we have to talk in new ways about faith.

It’s not like when I went to seminary and the discussion was about how to talk to people who had some church. Today if you are doing a new ministry, you better know how to talk to people who don’t have any church and are very skeptical of the institution. That’s the reality, and seminaries and others have to address it.

I teach a seminar on race, religion and ethnicity, and I have to give the students background on the United States and its long religious tradition, and the students are just amazed.

We still work on the assumption that everyone has a church background.