As a Lutheran theologian, and indeed as a Western Christian generally, I think the legacy of Martin Luther is remarkably instructive for helping to clarify what is at stake when we talk about freedom.

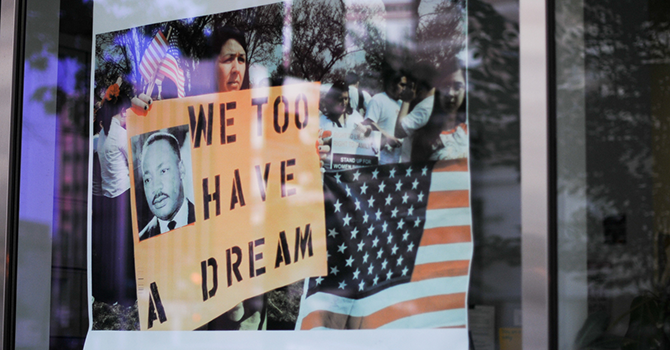

I’ve been considering this legacy as I prepare to teach a course on the Reformation as part of Christian Theological Seminary’s year of “Re|Formation” study. During this academic year, we’ll consider the legacies of Martin Luther and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. -- 500 years after Luther’s promulgation of the 95 Theses in Wittenberg and 50 years after the assassination of King.

But why, apart from the occasion of these anniversaries, is the Reformation’s legacy interesting for students being formed for ministry today? Why is it worthy of intensive, embodied study?

Luther himself changed the spelling of his surname from Luder to Luther as a nod to the Greek word eleutheros -- “free” or “freed” -- a move that would be echoed in 1934 when King’s father changed his son’s (and his own) name from Michael to Martin in honor of the German Reformer.

Most Protestant historiography prior to recent decades was downright hagiographic in heralding Luther as the prophet of religious, moral and political liberty. Films have used his struggles with the church as a kind of shorthand for elevation of the individual conscience over institutionalism or authoritarianism generally.

In the Protestant church itself, 1517 was seen as the inauguration of a new mode of freedom from tyrannical church authority, dogmatic superstition and other bogeymen of the post-Enlightenment West.

When I was growing up in the Lutheran Church, Reformation Sunday in October was generally a celebration of liberation from Roman Catholicism -- a celebration that could only stand on the foundation of the worst caricatures and misrepresentations of our Roman Catholic neighbors.

Even contemporary calls among politicians and pundits for religious groups viewed as too authoritarian tend to use the Reformation as a cipher, such as when people ask, “When will Islam have its Protestant Reformation?”

The thoroughly medieval monk became, ironically but durably, the first “modern” in the Western imagination, despite the falseness of this portrayal. We are not all Lutherans, but to the extent that we are tempted to equate modernity with freedom from constraint, we might plausibly be said to be Luther-an, at least in spirit.

Against the triumphalism of the previous 400 years, ecumenical labors in the last century have borne powerful fruit -- significantly, in the Lutheran World Federation’s planning of the entire 500th-anniversary commemoration (notably, not a “celebration”) in collaboration with the Vatican.

Most of the world’s Lutheran bodies now understand, in contrast to both Luther and the Lutheran confessions, that ecumenism is part of Lutheran Christian identity. This is perhaps the most salutary change in the landscape of Western Christianity of the past century.

What is emerging from that joint work is not the platitude that the Reformation signifies freedom itself. Instead, it is a recognition that the pain, brokenness, theological courage and clashing pieties displayed on all sides during the multiple reformations before and after the 16th century point toward the ways in which language of freedom in both faith and politics is contested space.

And it is precisely that contestation that has the most generative potential for formation of students seeking to proclaim the gospel.

If the Reformation were as unambiguously good as many of its champions have said, it would be thoroughly boring, and study of it would be irrelevant to ministry. But it is not without ambiguity and therefore is neither boring nor irrelevant.

In that spirit, I would offer the following observations.

Luther cared deeply about individual liberty, but he was also formed in a thick ecclesial context in which the practices and largely uncontested dominance of the church over all spheres of life were taken for granted.

For him, genuine gospel freedom relied upon faith formation in the home, access to Scripture, a richly sacramental worldview and regular participation in the life of the Christian community.

None of those things can be taken for granted now in the world -- or the church into which seminaries like mine send graduates. Some will try to restore these structures in contemporary forms; others will ask how Christian formation can proceed with new methods and community structures.

Further, seminary students and graduates today are in a position to appreciate the ways in which the shortcomings in Luther’s thought and person wrought disaster in his time and continue to vex the Protestant legacy throughout the world.

Luther’s disastrous venom against Jews, Anabaptists and other opponents he tended to (quite literally) demonize bore shameful fruit in his own era and reached a horrific nadir in the appropriation of his rhetoric by the Third Reich.

He claimed that Scripture is clear in its witness, even though he and other Reformers worked to supplement the bare text of Scripture with prefaces and commentaries. Many of these depended upon scholastically nuanced formulations around justification and sanctification. This, coupled with his lack of charity, meant that what began as ostensible liberation from arid dogmatism soon gave way to multiple competing dogmatisms among Protestants.

His deep reliance on the German princes and other political allies gave him a limited imagination about politics, which led, among other things, to his shameful reaction to the Peasants’ Revolt.

These are, I would suggest, not simply exceptions in Luther’s legacy but rather features; that is, the seeds of Luther’s failures are found in his own legacy and cannot simply be dismissed. And they are features that must be taken seriously both by Christians like myself, whose tradition bears his name, and by any Westerner (Christian or otherwise) who would look to him as a symbol of freedom.

For students seeking to ground the work of racial reconciliation, justice and reforming death-dealing systemic structures both in the world and in the church, grappling with this legacy is necessary and helpful.

It’s necessary because the church has joined in elevating Luther as a symbol for emancipation, and its leaders need to assess that elevation’s mixed record in fostering Christian unity or nuanced social understandings of human dignity and solidarity.

And it’s helpful because as the language of freedom in the public sphere increasingly finds itself signifying deep divisions of race, class, gender, sexuality and other hot-button topics, rooting out the pitfalls and potentials of the Reformation itself can shed light on which aspects of Luther’s legacy might profitably be carried forward, and which ones ought to be left behind.