When Fred Rogers was a child, he was sickly and bullied. They called him Fat Freddy.

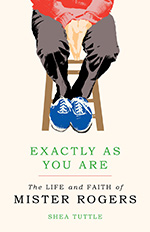

The bullying and isolation he felt could have turned him into a bitter person or someone exceptionally shy -- but instead, he spent his life offering love, affirmation and kindness to children all over the world. This is the man whose faith inspired Shea Tuttle, the author of “Exactly As You Are,” to write a book about Rogers’ theology and journey.

“Without using the overt language of faith on the air, Mister Rogers relentlessly preached his gospel: you are loved just the way you are,” Tuttle wrote in the book. “He testified to this love with conviction despite knowing well that not all children live in a loving home.”

“Without using the overt language of faith on the air, Mister Rogers relentlessly preached his gospel: you are loved just the way you are,” Tuttle wrote in the book. “He testified to this love with conviction despite knowing well that not all children live in a loving home.”

In the book, which came out in October 2019, Tuttle discusses liturgy, parables, Rogers’ “big feelings” and his life as an ordained Presbyterian minister. She quotes Rogers from 1994, saying: “You know, when I decided to look for work in television, I couldn’t possibly have known how I would be used. I’ve simply tried to be open to the possibilities God has made available to me.” Rogers is also the subject of "A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood," a film, starring Tom Hanks as Rogers, that premieres on November 22.

In the book, which came out in October 2019, Tuttle discusses liturgy, parables, Rogers’ “big feelings” and his life as an ordained Presbyterian minister. She quotes Rogers from 1994, saying: “You know, when I decided to look for work in television, I couldn’t possibly have known how I would be used. I’ve simply tried to be open to the possibilities God has made available to me.” Rogers is also the subject of "A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood," a film, starring Tom Hanks as Rogers, that premieres on November 22.

Tuttle spoke about Mister Rogers' generational impact and her work on the book with Faith & Leadership’s Katie Rosso. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: Tell me about the process of writing this book, how you went about your research into the life and faith of Fred Rogers.

Shea Tuttle: I did it over about two years, and I started out thinking I might just be writing a short essay. But then I ended up realizing that there was just so much that I wanted to say.

There’s actually a story that didn’t make it into the book about when Fred heard that a chapter of the Ku Klux Klan had made a phone recording to do these robocalls. But they made the recording sound like Mister Rogers, and it was really horrifying, I mean, Mister Rogers urging a child to do terrible things -- racist, awful things. Somehow this was happening, and Fred found out about it, and so he sued the KKK. I was just fascinated with that story.

So one of the first things I did was look up some of the old newspaper write-ups about it, and I called the lawyer who was a part of it. She ended up being a gateway into some other folks, because she said, “Oh, you should talk to this person, this person, this person.” For me, it was a delight to find out that I could call people who didn’t know who I was and just say, “Hey, I’m interested in Mister Rogers,” and they would tell me stories. It was kind of a revelation that, oh, these stories are out there, and all you have to do is ask for it.

F&L: You wrote in the beginning of the book that Mister Rogers was a part of your “becoming.” Tell me more about that, how he affected you on a personal level.

ST: It’s funny, because I know that he was really important to me as a child. There’s something about when I began to look up old episodes of “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” or to read about him or to encounter his stories -- there were ways that it just felt very significant to encounter him again, which is what gave me the sense that what he meant to me as a child was really substantial.

But in the intro to the book, I say that I don’t really have specific memories of watching him -- I don’t remember particular episodes or storylines or things that really moved me as a child. It felt like a mystery to me, while I was working on the book, to try to figure out why I feel so strongly about him even as an adult. In some ways, I still don’t know the answers to that, but that’s how a lot of people still feel when they encounter him.

I think that has to do with the way he takes children so seriously, the way that he offers this fundamental message of affirmation. It’s not that everything you ever do is good, but it’s just that you are good. You at your core are good and lovable and capable of loving. I think there’s something about that that’s very deep in who we are.

It’s universal that everyone wants to know that they are loved, and his whole work was about offering that to people. I think my best guess is just that I received that message as a child with as much eagerness as anyone else, and I can reconnect with it when I encounter him again.

F&L: There are a lot of things you could have written about him -- his dealing with issues around race, his philanthropy, his impact on media. So why did you choose to write about his faith?

ST: It just seemed clear that it was so important to him, and it was so much a part of who he really was. I think it permeated everything he did, more than really anybody knew. I think he was intentionally connected into a deeper reality of the world. His understanding of God was that there’s a loving mystery at the heart of the universe yearning to be expressed, and that’s what Fred sensed, and that’s what he walked with every day.

It feels to me that you can’t really tell his story without talking about that, because it was so much a part of who he was. I think for people who encountered him personally, that was evident.

It’s also my training. I worked for over seven years, and I’m still somewhat connected, at The Project on Lived Theology at UVA. The whole work of the project is about discerning where theological convictions are happening in the world and how they affect our behavior.

I think part of what I really loved was being able to read his life through that lens. I look at many things that he did that may or may not have been overtly theological, or expressed theologically, but we can see that they’re still theological. It’s just a lot of fun.

F&L: What throughout this process surprised you about Rogers’ faith? Did you take things from his practice of faith that have inspired you in your journey?

ST: I think the initial surprise was just finding out how much a part of his life faith was. He was not talking about God on “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.” I don’t know when I learned that he was ordained, but that sometimes comes as a surprise to people. Maybe it’s more common knowledge now. But then I discovered that he wrote a lot of letters, and often his letters would talk about matters of faith. This really was a present part of his life.

Much further in the timeline of the book writing for me, when I was done or nearly done, I started to get a sense of what it has meant to me to spend all that time with him. The thing I keep thinking about since I finished the book is that I’ve always been someone who claimed faith, or who was claimed by faith, whether I liked it or not.

I’ve always found faith to be kind of a struggle, or just -- I had plenty of doubts and questions and uncertainties. I’ve wrestled with that in different ways at different times, and I still have doubts and uncertainties. They don’t stress me out as much as they used to, and I’m more OK with that now than I was as a college student, for instance.

But even though it doesn’t worry me as much, I still struggle sometimes to be able to state very clearly and plainly what it is that I believe, because I’m not always sure. I think there was something that I realized with just a real joy about being able to state what Fred believes, because I think that he believed in what I hope is true about God, the world and people. He characterized them all by mercy and love and grace. I hope that’s true.

I always have to qualify [my own statements] a bit, and in telling Fred’s story, I didn’t qualify anything. I went to the extent that he did. It’s not that he never had any doubts or he didn’t have to work for the faith that he displayed, but I think he testified to that in a way that was, and remains, very powerful. Getting to testify to that through his life was kind of a surprise to me. What a joy that was to be able to offer that with a full voice, and I can work on doing that on my own, too.