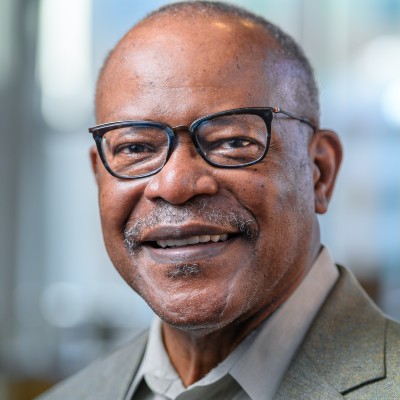

The Rev. Dr. Alvin C. Hathaway recalls the west Baltimore neighborhood where he grew up as close and nurturing, a community where church and family came together to care for those in their charge, including for his older brother Charles.

Born with an intellectual disability later diagnosed as autism, Charles needed support for his entire life. In the back of his mind, Alvin always wondered whether Charles could have had a better quality of life if his disorder had been better understood.

That nagging question resurfaced in 2019 when Daniel Weinberger, the director and CEO of the Lieber Institute for Brain Development, asked for Alvin C. Hathaway's help.

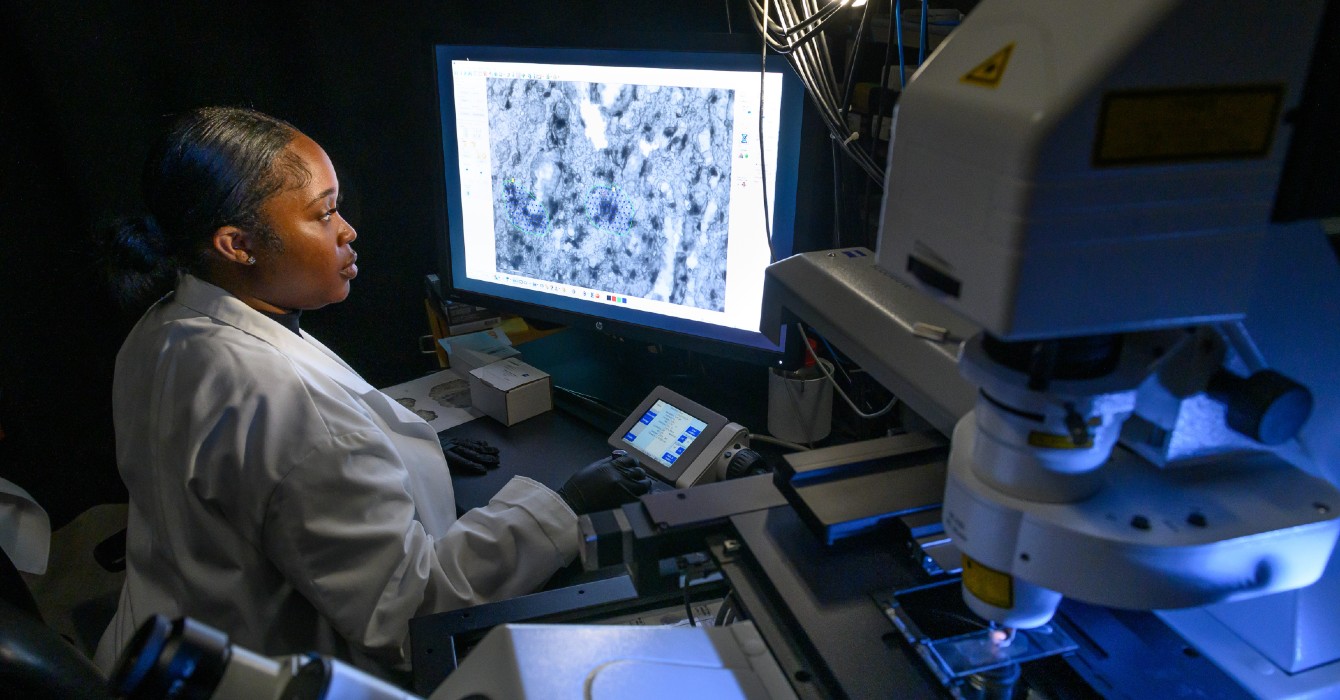

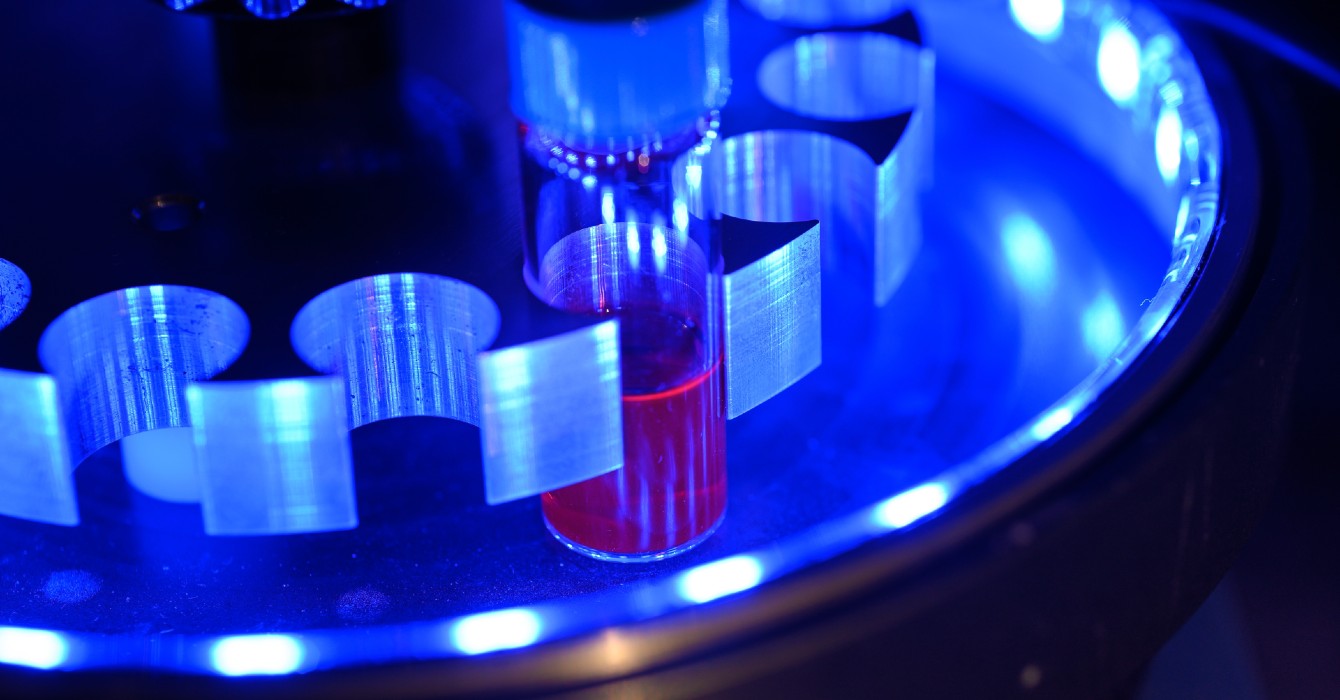

Weinberger had launched the Lieber Institute in 2010 to better understand diagnoses such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, PTSD, major depressive disorder, autism, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s. Several years later, he and his team of researchers realized that their efforts were hampered by the available research data, which left out a significant portion of the African genome.

This omission made it difficult to understand why African Americans are 20% more likely to experience serious mental health problems and at least twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than people of European descent. In 2019, the Lieber Institute launched the African Ancestry Neuroscience Research Initiative, the first-of-its-kind nonprofit created to increase African American participation in genomic neuroscience research.

How can you educate yourself and your constituents about health disparities in your context?

But the success of the project depended on diversifying the pool of research participants. In order to do that, the Lieber Institute needed to forge connections and build trust with Baltimore’s Black community. When the nonprofit considered who could help build that bridge, Hathaway quickly rose to the top of the list.

He eagerly accepted the challenge. At the time, Hathaway was senior pastor of west Baltimore’s Union Baptist Church and had established a reputation for successful community organizing and activism.

“When I looked at the dearth of Black persons in terms of participants and also professionally, that has been a driver for me,” he said. “I saw an issue of social justice.”

If you need to build a bridge between people, who is the most qualified to build it?

He also saw the African Ancestry Neuroscience Research Initiative as an opportunity to create a template for inclusive participatory research that engages and respects the affected community. The relationships many Black people have with science and medicine are fraught with skepticism and distrust. While their concerns are based in a long and well-documented history of medical exploitation and neglect, the lack of Black participation in research and clinical trials has negatively affected the health of minoritized communities overall. Despite myriad attempts by scientists, practitioners and others to reduce health disparities over recent decades, African Americans continue to have worse health outcomes, and better research data is one factor that could help.

Throughout its history, the Black church has been viewed as a trusted narrator central to providing educational, financial and health information to the community. A growing number of health entities believe that forming partnerships with Black faith leaders is an expeditious way to build stronger, more diverse relationships, bring communities of color into research, and make those communities active participants in improving their own health.

A life of advocacy and activism

Hathaway gained an early understanding of how to bring people together for collective action during his first foray into community organizing. In 1977, he worked with Baltimoreans United in Leadership Development, a nonprofit designed to develop leaders to take action on issues such as housing, schools and employment.

“We understood power as the ability to act and always asked, ‘How can we use our collective power to change conditions and situations?’” Hathaway said.

His focus shifted to include health activism decades ago when he and his wife enrolled in a longitudinal study on aging. That’s when he first understood how racial disparities impeded access to high-quality health care. By this time, Hathaway had answered the call to ministry and added a spiritual component to his advocacy. He organized a coalition of 18 churches in southeast Washington, D.C., that later also operated sites for health screenings.

Over his 14 years as head pastor at Union Baptist, Hathaway initiated several community-based health programs, like creating a group of health navigators within churches, organizing routine health screenings for members, and leading an ombudsman program to monitor seniors’ care in nursing homes.

Can your church get involved in supporting public health?

The whole time, Hathaway’s family medical history deepened his interest in mental health. While earning his master of theology degree at St. Mary’s Seminary in Baltimore, he had deep conversations about the health-spirituality connection with one of his professors who also happened to be a medical doctor. He credits those insights for forming his musings into a concrete ideology.

“The fundamental connection between faith and mental health begins with spirituality. I believe that spirituality is what grounds and sustains you,” he said.

He cites Philippians 4:8 as a biblical connection between spirituality and physical health. “Whatsoever things are true, whatsoever things are honest, whatsoever things are just, whatsoever things are pure, whatsoever things are lovely, whatsoever things are of good report; if there be any virtue, and if there be any praise, think on these things” (KJV).

A growing trend

The Lieber Institute is just one of a number of collaborations that have developed between health, academic, and research institutions and Black faith entities.

When Goldie Byrd became the director of the Maya Angelou Center for Health Equity at Wake Forest University School of Medicine in 2018, she insisted on two things: locating the facility in the Black community and establishing a close connection with the faith community.

“I am a product of the church, and that has always been a big factor in my work,” Byrd said.

She connected with the Rev. Lamonte Williams, a local pastor who believed that the Black church had an obligation to care for its parishioners’ physical, mental and spiritual health. He believed a collaboration with the Maya Angelou Center would not only provide grounding for the health care institution but also have a trickle-down effect that would improve the health outcomes for the faith leaders, their congregants and their communities.

“There is this notion that the Black church puts all our emphasis on going to heaven and we don’t really care about the quality of life while we’re here,” Williams said. “I preach to my local congregation that a quality life is accessible to you but you have to be intentional about trying to make sure it happens.”

He uses 3 John 1:2 as the guiding principle: “Beloved, I pray that you may prosper in all things and be in health, just as your soul prospers” (NKJV).

Williams helped form the Triad Pastoral Network and establish an official working relationship between the Maya Angelou Center and faith leaders throughout the central North Carolina region, which includes Greensboro, Winston-Salem and High Point.

The collaboration began with a yearlong series of listening sessions between members of the clergy from every faith and denomination, including an imam and a rabbi, and Maya Angelou Center staff to determine their respective expectations.

What are some theological misconceptions that might negatively impact people’s physical health?

“Working with faith communities is not a novel idea,” said Williams, who has joined the Maya Angelou Center as a community liaison and outreach specialist. “The challenge is avoiding the minefields.”

The COVID pandemic illuminated health disparities and inequities in historically marginalized populations and tested the viability of the fledgling network.

“Many pastors were struggling with how to navigate this type of once-in-a-lifetime pandemic,” said Williams, now the pastor of Bethlehem Baptist Church in Warrenton, North Carolina. “As a trusted voice, we were instrumental in galvanizing the faith leaders and gathering information on the reticence in the Black community around the vaccine. First, we got them to see the necessity and then we asked them to be the ambassadors to the congregation.”

In addition to a well-founded distrust of the medical establishment, the reason many Black people aren’t involved in medical research is simply that they aren’t asked. A 2020 study found that some clinical trial recruiters intentionally withheld clinical trial opportunities from African Americans because they believed them to be less capable of complying with the required rules and protocols.

What has the pandemic shown you about understandings of health in your context?

In addition to improving coronavirus vaccination rates and understanding, the Triad Pastoral Network has assisted the Maya Angelou Center in conducting research studies on self-management of chronic pain among special populations, as well as Alzheimer’s disease and genetics in African American and Puerto Rican populations.

Williams credits Byrd for the success of the collaboration by bringing in the faith leaders from the beginning and making sure all participants stayed in their respective lanes.

“You have a scientist who’s not trying to be a faith leader and faith leaders who are not trying to be scientists,” Williams said.

Acknowledging past wrongs

In an effort to ensure that clinical research participation accurately reflects the communities, Duke Health launched the AME Zion Health Equity Advocates & Liaisons partnership with a network of 18 faith leaders representing 17 African Methodist Episcopal Zion churches across North Carolina.

“Duke Health said, ‘You have the kind of power that can make a difference as it relates to people’s health,’” said the Rev. Julian Pridgen, the senior pastor of Durham’s St. Mark AME Zion Church.

That resonated with his desire to make health care a central part of this ministry. He had long viewed the church as a vehicle to help African Americans get more involved in their health.

“Historically and traditionally, Black preachers have had to talk about all issues of life from the pulpit,” Pridgen said. “Caring for the whole person is part of our duty as Christian leaders. It’s part of the gospel we preach.”

Health Equity Advocates & Liaisons participating clergy underwent intensive training about the importance of clinical research, informed consent, protection of research participants, advances on ethical standards, and research design and methods. And they talked about the past mistreatment of Black people by medical professionals and other scientists.

Pridgen recalls lengthy discussions about the Tuskegee experiment in which Black men with syphilis were denied penicillin, and Henrietta Lacks, a young Black mother of five whose cancer cells were collected for research without her knowledge or consent.

Is there training you can undergo to be a better resource for your constituents’ health?

In return, the pastoral leaders share their cultural expertise to educate research teams and provide feedback and guidance to effectively and respectfully improve population health through research. To date, Health Equity Advocates & Liaisons clergy members have engaged their congregations in a variety of health studies and wellness initiatives and as research participants.

Five years after Hathaway co-founded the African Ancestry Neuroscience Research Initiative, his vision of inclusiveness is bearing fruit. The organization’s engagement has moved beyond Baltimore to include minoritized people in cities across the country. In addition, the African Ancestry Neuroscience Research Initiative has raised nearly $2 billion for clinical studies, amassed the world’s largest collection of Black brains, and produced groundbreaking research that is beginning to unravel the mystery of the brain. This network is being built out, and the model is considered a template for similar initiatives.

After 14 years at the helm of Union Baptist, Hathaway stepped down as senior pastor in 2021. However, what he calls his work as a servant leader has broadened and continues to expand.

“I want to influence influencers, identify leaders of groups with defined followings, so I can influence a larger group by developing relationships,” he said.

Questions to consider

- How can you educate yourself and your constituents about health disparities in your context?

- If you need to build a bridge between people, who is the most qualified to build it?

- Can your church get involved in supporting public health?

- What are some theological misconceptions that might negatively impact people’s physical health?

- What has the pandemic shown you about understandings of health in your context?

- Is there training you can undergo to be a better resource for your constituents’ health?