COVID-19 has hit communities of color hard in New York City. And even since vaccines have become widely available this year, there has been a great deal of hesitation among Black and brown New Yorkers to get it.

“For every 100 people, there are 100 reasons why they are reluctant to get the vaccine. It really comes down to local issues,” said David Gross, the general counsel at Community Healthcare Network, a nonprofit providing access to affordable health care throughout the city.

“But if you have a pastor preaching from a pulpit, that’s a different strategy,” he said. “A new way to tackle hesitancy.”

And an even more effective way? Not just talking about it from the pulpit but setting up vaccine clinics inside the churches where people feel safe.

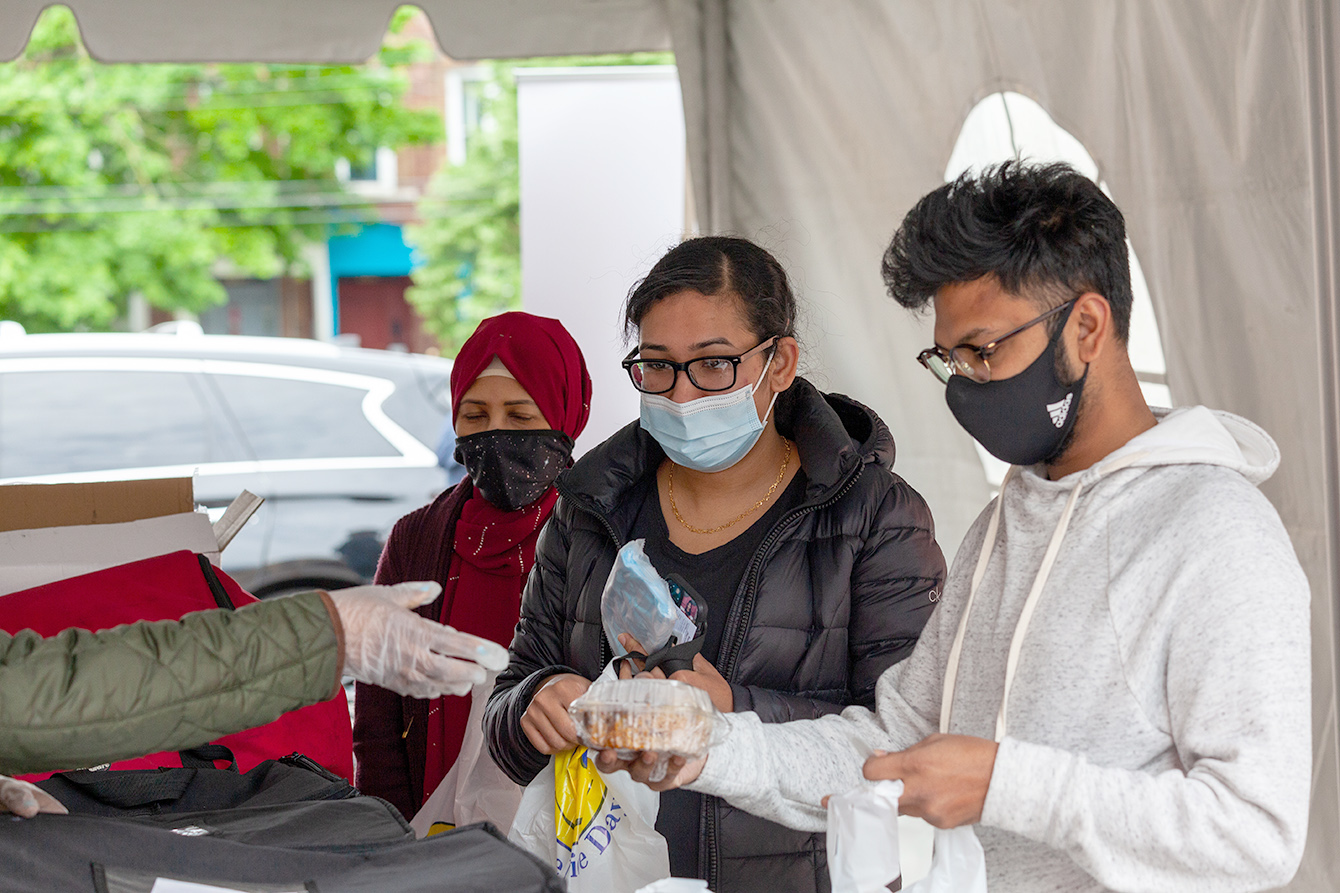

This past spring, Community Healthcare Network (CHN) and Stop the Spread, a national organization that convenes private sector support for COVID-19 response programs, did just that. By partnering with predominantly Black and brown churches across New York City, they designed and set up vaccine clinics that adopted different models to address the particular needs of each community.

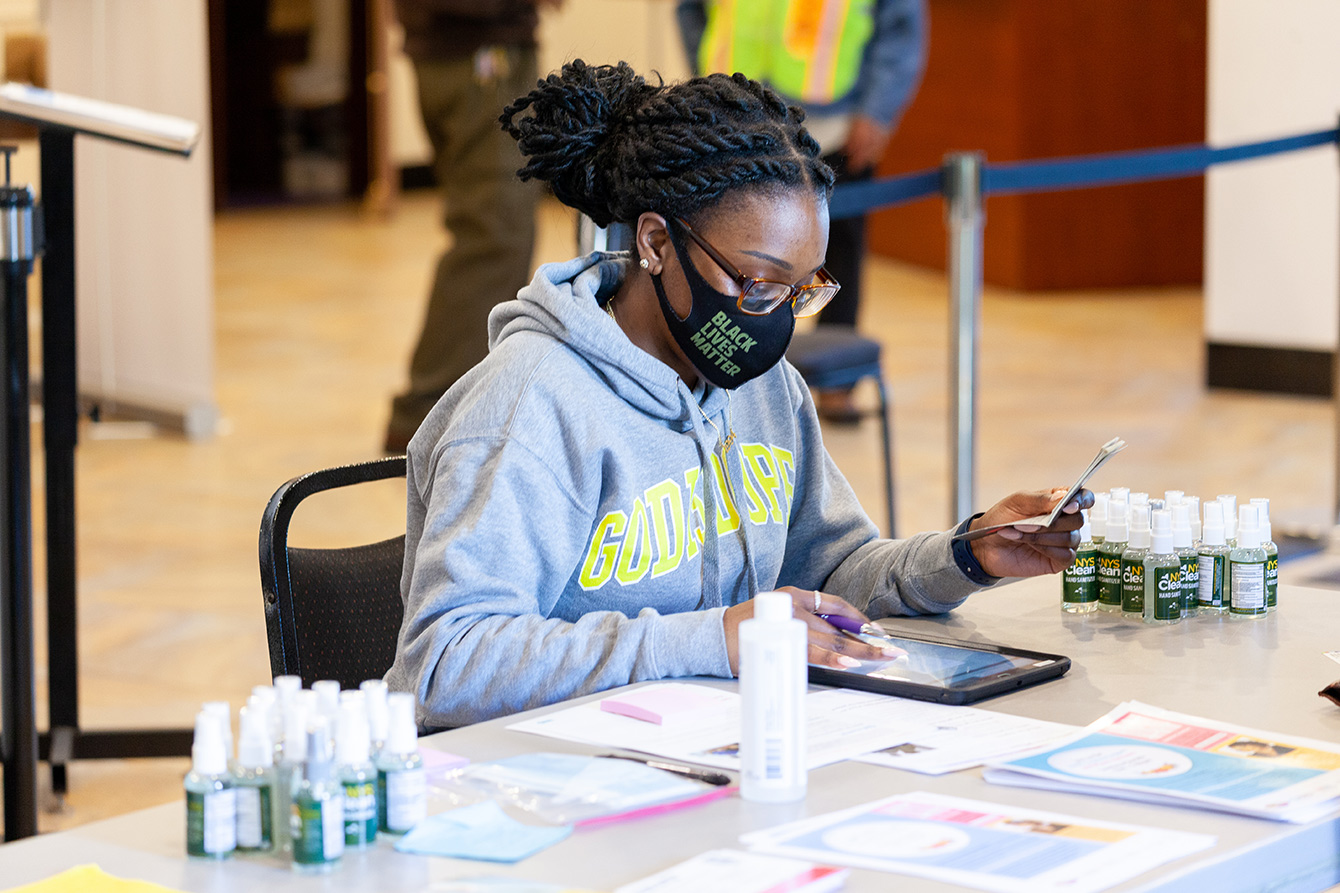

And as the vaccination effort progressed, pastors and partners continued to innovate, using pop-up clinics, word-of-mouth, and even quick-response backpacks to make vaccines available in an environment where people felt they were cared for and their concerns heard. The Vaccine+ model offers other services along with the jab.

“When people had questions, we didn’t answer with flowing theology,” said the Rev. Dr. Tyrone Stevenson, the senior pastor at Hope City Church in Brooklyn. Half the battle, he said, was just letting people talk, expressing what they were feeling and thinking. “We were just having conversations, not belittling them.”

Nationally, 70% of Asian people had received at least one shot by Oct. 18, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). Hispanic people had a 52% rate, and Black people, 47%. And while white people had a 54% vaccination rate, they still represent the majority of people (60%) who are unvaccinated, according to KFF. White evangelical Christians have been among the least likely to be vaccinated.

In its first iteration — which operated from April through July of this year — the partnership set up walk-in vaccination clinics at churches in neighborhoods hit hard by COVID-19.

“We help to bring organizations together that might not traditionally partner to co-design and stand up the programs,” said Molly Chidester, the chief operating officer of Stop the Spread, which supported vaccine efforts in New York City with a $1 million grant from Google.

By the end of September, CHN and Stop the Spread had hosted more than 85 community pop-up events with more than 25 community and faith-based partners, administering more than 30,000 vaccines. Roughly one-third of the people said they came in because a friend or family member suggested it, Chidester said.

“We staffed the vaccine clinics and outreach teams with members of the church who already have trust and relationships with the community, and it worked.”

Relationships drive the effort

Throughout the summer, they started seeing huge demand, with more than 22,000 vaccines delivered across four churches — in Harlem; Washington Heights; Jamaica, Queens; and East New York, Brooklyn — where 70% of the people who came in identified as Black or Hispanic.

When the demand tapered off as local needs were met, the partnership shifted to pop-up clinics, piggybacking on church-sponsored events, such as back-to-school nights and barbecues.

And to further streamline the effort, Dr. Luis Freddy Molano, CHN’s vice president of infectious diseases and LGBTQ programs and services, came up with an ingenious solution: the backpack model.

“We put everything together that we need for a vaccination station and realized that we can put it all in a backpack. I can go to any church at any given time and set up in five minutes. We only need the vaccinator, the nurse,” said Molano, who on any weekend has up to five backpack teams operating throughout the city.

Yet boosting vaccine rates in hard-to-reach communities is about more than just physical access. To help persuade hesitant community members to take the vaccine, partner churches conducted outreach — online, phone banking and in the community, pounding the pavement trying to drum up demand.

“We did a lot of walking to let people know,” said the Rev. Yolanda Mitchell, a minister at the Church of God in East New York, Brooklyn. Mitchell also served as co-director of the vaccination site. “One of the ladies at the church sealed masks in plastic. I would stop off at local businesses — hair salons, barbershops — and say, ‘Do you need masks? Oh, and by the way, the Church of God is a vaccination site.’

“We were not beating people over the head, saying, ‘You are going to die if you don’t do this.’ We would ask, ‘What do you think? What do you feel?’” Mitchell said. “We tried to make it a place that was friendly and inviting.”

Members of the Greater NYC Black Nurses Association were on hand to answer questions, but as CHN’s Gross said, “The nurses are not going to convince people to get the vaccine. It’s really the churches and their relationships with people that will be the driver.”

At Convent Avenue Baptist Church in West Harlem, minister Requithelia Allen was in the driver’s seat.

“For people of color, there still is a great deal of resistance and mistrust, given some historical factors,” Allen said. “Overcoming hesitancy was a community effort.”

They promoted the vaccination clinic across all of their online platforms, during virtual services and in public announcements.

“To get people into the clinic, we literally had two gentlemen on the street every day. They said, ‘Did you do it yet? Why don’t you come in to have your vaccine?’” Allen said.

Allen had fallen ill with COVID-19 early in the pandemic, and sharing that helped alleviate people’s concerns.

“People want to see that you are not just talking the talk but living it,” she said.

The fact that she had survived COVID and told community members that the side effects of the vaccine were nothing compared with the illness itself had an impact.

Fear tactics, Allen said, had no place in the process. Her approach to persuading folks to take the vaccine was pastoral. “You want to encourage people to feel well — that this is not coercion but the best thing for them.”

There were many good days, she said. Days when they had plenty of walk-ins and were able to persuade those who were nervous about it to get the vaccine.

On those days, Allen said, “you could sense the joy and peace in the room. For me personally, it was one more reason to be thankful — that God had done something extra special that day.”

But there were also days when they failed to use up all the doses they had.

“The bad days made me do a little more praying to fight against disappointment,” she said.

“Our job,” said Stevenson of Hope City Church, “is to do what Jesus did. Meet people where they are and take them on a journey to where they need to be.”

Stevenson was prepared for the hesitancy. He was prepared for the rumors and misinformation about the vaccine.

“But what surprised me was the depth of the conspiracy theories. It came down to a complete mistrust,” he said. “More than anything else, I heard, ‘White America has found a way to get rid of us.’”

But he worked with June Omadela Carrington — who has a master of public health degree and a Ph.D. in medical anthropology and runs the church-affiliated nonprofit Hope Empowerment and Development Zone (HEADZ) — to keep the conversation going, hosting myth-busting sessions where people could ask questions.

Regardless of the concern, they tried to find an answer. Some community members, for example, were worried that there was metal in the vaccine, Carrington said. “I would say, ‘OK, I had the vaccine. Let’s go find a magnet and see if it sticks.’”

Addressing trauma with more than vaccines

Stevenson used the pulpit to promote the vaccines as well as the mental health services available through the clinic. Funded by Stop the Spread, the counseling services were offered through what is referred to as the Vaccine+ model.

Vaccine+ optimizes the 15-to-30-minute window when people must be monitored after the injection. This may involve health care or social services, such as diagnostic screening, food support or mental health.

“Vaccine+ looks different in every church,” Chidester said. “We start by listening to the community’s needs and design from there.”

For Stevenson, mental health support was a priority for his congregants and his community.

“We identified counseling as a need because our people are traumatized. There’s trauma that our community never interprets as trauma. We interpret it as living in the ’hood. The gunshots — hearing them is the norm, knowing that this is what we have lived our entire life,” Stevenson said. “We already were in crisis, and then the pandemic hit.”

According to Stop the Spread, about a third of the people vaccinated at Hope City Church have accepted the Vaccine+ offer of six free counseling sessions, either online or in a separate space provided by the church.

This demand reflects both the high stress levels within the community and Stevenson’s efforts to normalize mental health care.

“It’s taboo in the Black community. You don’t go to counseling. That means something is wrong with you,” Stevenson said.

So he puts it in his sermons. And he talks about Jesus’ own battle with mental health.

“It’s hard for people to acknowledge the humanity of Jesus. I spend a lot of time showing the hungry and cold Jesus. The Jesus who had a mental health episode in the garden of Gethsemane” (Matthew 26:36-46).

Stevenson also casually mentions his own conversations with his therapist.

“I can see the faces on the people: ‘Did the pastor just say his therapist?’” Stevenson laughs. “Sometimes I joke and say, ‘You all think I don’t have a therapist? Besides Jesus, who do you think I take these burdens to?’”