When Jewish Family Service of San Diego responded to the plight of a particularly vulnerable group of immigrants five years ago, the organization didn’t have a long-range plan.

JFS learned in 2018 that mothers and their children who sought asylum at the border were being released from immigration custody onto the streets with no support. The nonprofit, along with other local organizations, stepped in to create a place where these families could rest, eat, and find assistance in making their journey to loved ones who were waiting to receive them across the United States.

“It was the right thing to do,” said Michael Hopkins, the CEO of Jewish Family Service. “We didn’t say, ‘What is this going to look like in three months or six months or a year from now?’ We were present in the moment and said, ‘This is what we need to do tonight.’”

When the shelter started, the volunteers who staffed it — and the JFS employees who shifted from their regular tasks to running it — had no idea that it would still exist today.

But in November 2022, the shelter welcomed its 100,000th guest, and it has welcomed many more since then. What is now the San Diego Rapid Response Network Migrant Shelter has become a cornerstone of asylum processing in the region. For the many who fled their homes only to risk their lives further on the dangerous route to the border, the shelter has become a respite, a place where they can rest for the first time in months.

When have you responded to an urgent need? What does it mean to respond — tonight! — without a long-term plan?

That includes the Léon family, whose experience is similar to that of thousands of asylum seekers over the past several years. The February night before the family of five crossed the U.S.-Mexico border, they had slept on the floor at the Tijuana airport.

Originally from Venezuela, they had arrived from Ciudad Juarez, another Mexican border city where they’d been waiting for their appointment, made with a smartphone app, to request asylum at a San Diego port of entry. That cold airport floor was not the worst place they’d slept since deciding their best chance for survival was to head for the United States.

They had trekked through a deadly jungle, ridden with other migrants atop an infamous freight train and struggled constantly to find food or a place to sleep. Along the way, Victor Eduardo Léon, 28, had dressed as a clown and performed in the streets to gather enough money for himself and his wife, two children, and mother to keep going.

After they finally reached U.S. soil, they were taken on a bus to a hotel where a migrant shelter rents rooms for arriving asylum seekers, people who have fled their home countries and are hoping to be recognized as refugees.

Under U.S. immigration law, that means they have to show that they have a well-founded fear of persecution in their home countries because of their race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a social group closely linked to their identity, such as the LGBTQ community. They also have to show that the persecution comes from the government itself or a group that the government cannot or will not control. Applicants are legally allowed to remain in the U.S. while their status is pending.

“The first thing we did when we got to the room was thank God,” Léon said.

“We thanked God and then lay down in that rich bed,” his mother, Yelitza Josefina Léon, said.

The family slept for about 12 hours and would have kept sleeping but for the knock on the door by a shelter staff member bringing them breakfast.

‘That was once us’

The shelter represents an act of faith. Faced with a change in government policy that left newly arrived asylum-seeking families stranded on the streets of San Diego with little information about where they were or how to contact loved ones, Jewish Family Service took guidance for its actions from holy text.

“The commandment to be kind to the stranger or welcome the stranger is in the Torah more than any other commandment — 36 times,” Hopkins said. “My understanding as to why it’s such a central tenet is that it is part of our shared experience within the Jewish community. The notion of being outsiders is part of how we see the world, and so welcoming the stranger, while it is obviously the right thing to do — it is also in the context of ‘That was once us.’”

How does your congregation live out its most-quoted scriptures?

JFS of San Diego was founded more than 100 years ago by a group of women who learned that there were Jewish migrants stuck at the southwest border, many fleeing a civil war in Ukraine, according to Hopkins.

By 2017, the organization operated several immigration-related programs, including efforts in refugee resettlement and pro bono legal representation.

That year, the organization joined with others under the collective San Diego Rapid Response Network to create a hotline to respond to immigration enforcement raids.

In late 2018, Immigration and Customs Enforcement decided to stop helping asylum-seeking families make their travel plans before releasing them from custody after they crossed the border. Border officials began leaving these families on the streets around San Diego County.

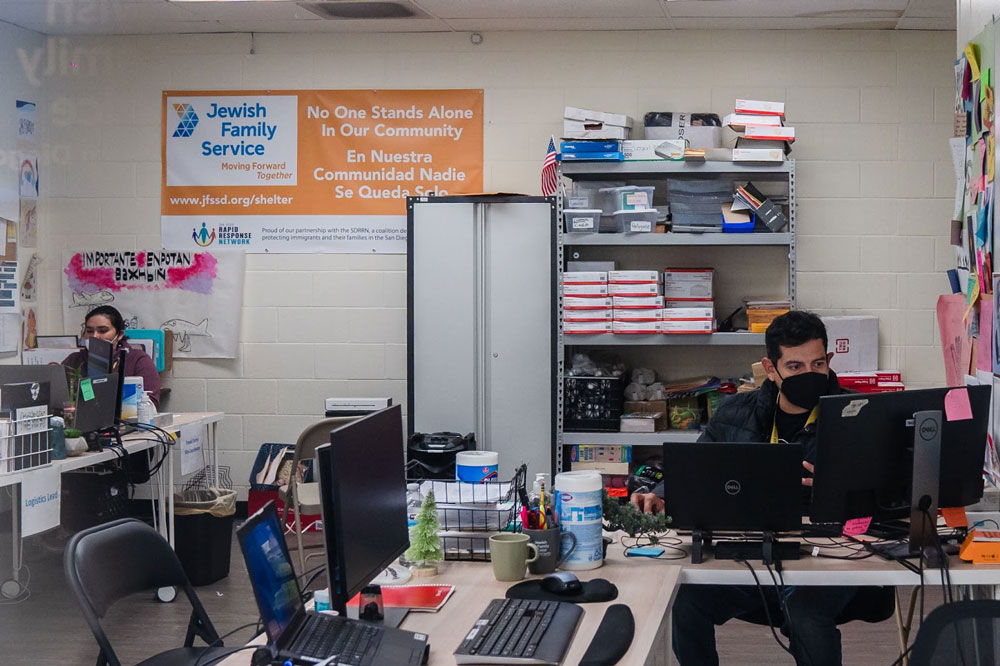

Calls started coming in to the hotline asking for help. The network organized a response, with Jewish Family Service leading the shelter efforts.

JFS applied its knowledge from working with refugees as well as from working with homeless populations. It also brought the immigration legal team in to ensure that the shelter was responding to the range of the guests’ needs.

“As an organization, it was in some ways a cousin of the work that we were already doing,” Hopkins said.

How does your congregation listen to the most vulnerable people in your community?

Kate Clark, the JFS attorney who took on running the shelter, emphasized the importance of caring for shelter guests holistically.

That meant finding solutions for the gaps in the organization’s knowledge, like providing medical care and managing the public health environment of a shelter. They found a partner in the University of California San Diego School of Public Health.

Building and flying

They set up the shelter as a congregate facility, with rows of cots organized in each room to the capacity allowed by the fire marshal. Some nights, the number of people released from custody at the border was higher than the limit set for the space they had. The network scrambled to find additional accommodations and sent volunteers to bus stations with snacks and phones to help the families connect with their loved ones and get tickets to continue traveling.

They didn’t know where the funding to sustain the shelter would come from. They often didn’t even know where the shelter would be a few nights into the future. It initially moved frequently before getting a longer-term home, first from the county of San Diego and then from the state of California.

When the pandemic hit in early 2020, the number of asylum seekers crossing the border dropped dramatically. For the few who came throughout the summer, Jewish Family Service found hotel rooms to mitigate the risk of COVID-19.

Later, as more asylum seekers began to arrive again, many fleeing conditions worsened by the pandemic, JFS ramped up its staffing to respond and continued to house its guests in the hotel rooms. What was once largely run by volunteers became a staff-based effort with financial support from the state and federal governments.

Even today, the shelter’s needs continue to evolve.

“We would say, ‘We’re building the plane as we fly it,’” Clark said of the shelter’s early days. “It still feels like that four years later. I don’t know what that says about our building skills or our flying skills. It goes to the nimbleness in this work that’s required to respond to the challenges that are before us.”

How have the ministries of your congregation pivoted in the last few years? What support do vulnerable people in your community need today?

Clark emphasized that one of the most important lessons her team has learned is the need to stay agile.

From month to month, the national identities of the asylum seekers served by the shelter can shift dramatically because of border policy changes as well as world events that give rise to new refugee situations.

In 2019, the shelter generally served families from Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, Haiti and Mexico. That meant having staff and volunteers who could speak Spanish and Haitian Creole, as well as having access to speakers of indigenous languages from those countries.

Toward the end of 2020, Russians became a prominent nationality group among shelter guests. When Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2022, that trend increased, and Ukrainians began to arrive as well. The shelter responded by finding people equipped to converse with its guests in Russian and Ukrainian.

Since January 2021, the shelter has hosted more than 60 nationalities. Clark said she strives to make sure each guest is received in a culturally competent and trauma-informed way.

Looking ahead

For Hopkins, one of the most important factors in operating the shelter is a key trait of his staff: empathy.

He said his team did a strength-finders activity and scored particularly highly in empathy. That is crucial in being able to identify the needs of the shelter’s guests, he said, and it connects back to the Jewish faith.

“The text talks about loving that stranger as if it was yourself,” he said. “In every way, we try to think about the people that we’re serving — how scary it has to be in a country where you don’t speak the language, you don’t know how things operate. What can we do to create an environment where, while they’re in our care, they really, truly feel like they’re cared for?”

That empathy in action plays out in countless practical ways. It means making sure that there is water readily available for the guests, as well as fresh fruit, he said.

It means guiding them through the airport to their flights. Some of the shelter guests have never been on an escalator before arriving at the San Diego airport, let alone an airplane. Local airline staff and Transportation Security Administration officials have grown used to seeing shelter staff with passes to accompany asylum seekers through security to their gates.

It also means making sure the travelers understand the documents they’ve received from immigration officials and the next steps they’ll need to take when they arrive in their new home cities.

What practical help can you provide to the confused or lost?

It means advocating with every level of government to make the work possible. And it means being watchful for issues in how the system is functioning, raising awareness about problems like ongoing family separation at the border or mistreatment of pregnant women in immigration custody. Jewish Family Service’s legal team has helped asylum seekers file complaints on such issues through its shelter work.

In late 2022, more asylum seekers began arriving without an intended destination, without a friend or family member to receive them and get them started in their new lives. That has complicated the work for JFS, because these families stay longer in their care before traveling on, limiting the organization’s capacity to receive new arrivals.

Governors in Texas and Florida have sent asylum seekers on buses and planes to cities in other states, regardless of where they intended to go.

These developments have increased the need for migrant shelters in more parts of the United States to receive asylum seekers and help them travel on or get settled.

Local governments in several cities across the country have opened shelters to try to address the needs of the new arrivals. Several localities have met with Jewish Family Service to learn best practices for running a migrant shelter.

Still, Hopkins said, there is a need for more help. He called it an opportunity for faith communities to live their values.

Life-threatening situations are best addressed through collaborations. With whom are you working? In your community, whom do the people living in challenging circumstances trust most? What can you do to work alongside others to encourage and support them?

In the Jewish faith, he said, the Passover Seder is a time to imagine what it was like to be an enslaved Jewish person centuries ago. He hopes that faith communities can use a similar exercise to find empathy with arriving asylum seekers and said that his organization is willing to share what it has learned so far.

“I would hope the faith community opens its doors and treats those who are new to their community as if it was one of them,” Hopkins said. “That they see those individuals as being on a path that their family was once on.”

Questions to consider

- When have you responded to an urgent need? What does it mean to respond — tonight! — without a long-term plan?

- How does your congregation live out its most-quoted scriptures?

- How does your congregation listen to the most vulnerable people in your community?

- How have the ministries of your congregation pivoted in the last few years? What support do vulnerable people in your community need today?

- What practical help can you provide to the confused or lost?

- Life-threatening situations are best addressed through collaborations. With whom are you working? In your community, whom do the people living in challenging circumstances trust most? What can you do to work alongside others to encourage and support them?