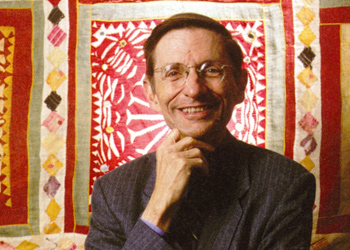

The world is going through its most important transformation since the agricultural revolution, said Bill Drayton, the founder and CEO of Ashoka, a global organization that offers venture capital for social entrepreneurs.

“We’re transitioning from a few people running everything and everyone else doing repetitive functions ... to a ‘changemaker world,’” said Drayton, who is widely regarded as a pioneer in the field of social entrepreneurship.

Drayton grew up during the time of the civil rights movement and was heavily influenced by the Gandhian movement. After attending Harvard University, the University of Oxford and Yale Law School, Drayton was a consultant at management consulting firm McKinsey & Company and an assistant administrator at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

He established Ashoka in 1980. Named after a third-century-B.C. Indian emperor, it is dedicated to supporting the “citizen sector” in effecting social change. Its motto is “Everyone A Changemaker.”

Drayton spoke with Faith & Leadership about how to be a “changemaker” and what role leaders and religious institutions can play in a “changemaker world.” The following is an edited transcript.

Q: What does it take to be a “changemaker”?

[Changemakers] give themselves permission to see the world, to see things that could be better, and to believe that they can actually make things better.

[For example,] Mary Gordon, an Ashoka fellow in Canada, said children are not learning empathy. The education system isn’t addressing it, and parents don’t know how to give children this skill in many cases. Mary gave herself permission to see the problem and to find a solution that would change all the schools, not just her school.

She brings an infant to a first-grade or third-grade class. The infant [wears a] T-shirt ... labeled “the professor” and resides on a green blanket with mom or occasionally dad nearby. The students, not the teacher, have the job of figuring out what “the professor” is saying -- which is not that hard, because infants are really good at nonverbal communication -- and then what “the professor” is feeling. The students observe the parent-child empathetic tie, which is highly developed and very strong. The kids learn [empathy] and that everyone has the central inherited drive to be a part of society and to be a good person at a very significant degree.

This has gone from two classrooms to 14,000 classrooms in 14 ½ years, and is part of a larger collaboration that we have under way worldwide to make sure that all children master empathy.

Now when you listen to this story, this is not a solution that anybody else couldn’t do, but Mary gave herself permission to see the problem, to imagine a solution and to imagine how she was going to spread it across the world.

So the first principle [to being a changemaker] is to give yourself permission. Be polite to the people who say you can’t do something, because that’s just an expression of the degree to which they are limited. Don’t let them limit you.

Q: After you give yourself permission, what are the next steps to “changemaking”?

Creativity in both goal setting and problem solving. That’s the first criterion.

Second is entrepreneurial quality. What is that? It’s not getting things done or leading or managing; millions of people can do that. It’s a deep drive to change society for the good of all -- so much of a drive that you can’t be satisfied in life unless you have actually seen that change come about all across society, not just in one community.

That means that [changemakers] care about “how to” questions. How are we going to get from here to there? How do the pieces fit together? How do you solve this problem? How do you seize that opportunity at the same time that [you’re] wedded, in the full sense of that verb, to the goal?

So they typically are double dominant, right and left brain. And they’re not ideologues. They’re open. They’re listeners. They’re realists, because they cannot be satisfied in life unless this thing actually works. That’s a very strong discipline. That’s entrepreneurial quality.

The third is not about the person; it’s about the idea. Will the idea spread? Does it have legs? How far will it go? How many people will it impact? How importantly? How about officially?

The final is ethical fiber. If you’re an entrepreneur and you’re trying to introduce a change, you’re asking people to do outlandish things that they wouldn’t normally do, and you’re asking them to be among the first to do it. Why will people do it? It’s not because of the words. If you say something really stupid, that could hold you back. But when the entrepreneur walks into the room, people know deep inside them, “I can trust this person.” They know that the person is married to the idea, and they sense the energy and the commitment and the togetherness of the person. That’s why they say “yes.” If there’s one person in the room the other people don’t trust, it kills the conversation.

Those are the four criteria -- creativity, entrepreneurial quality, the social impact for the good of the new idea and ethical fiber.

But it’s ultimately rooted in a very simple thing: Do you want to do good for the world, and will you give yourself permission? The first one almost everyone wants to do. The second is the problem. If people would just realize that they have the power, if they allow themselves to use it, the world would move ahead really quickly.

Q: How can leaders create an environment that encourages people to give themselves permission?

Once people realize that the new game is “everyone a changemaker” and that everyone can play, their institution needs to be managed differently. They can’t be a hierarchy anymore. It has to be a team of teams.

If you say to the people leading a religious house, “This is a time when everyone needs to master the skill that underlies being a good person” -- isn’t that something that religion should be engaged in?

And by the way, if you lead in this area, you’ll be bringing huge value to society and to the people you’re serving, and your house will be vital. It will gain strength from doing this.

That’s the main strategic opportunity for a school or a religious house. Give people an understanding of their strategic environment and what their strategic opportunity at this moment in history is, and some of the people will respond.

Then you’ve got to help them do that. In doing that you are helping them become changemakers, which is, of course, helping them to be a more powerful contributor to the good, allowing them to express love and respect and action at a higher level. There is nothing that is a greater gift to anyone.

I think that’s really what leadership for society or for an institution is about: helping people see the strategic environment and the strategic opportunity and [that they can] give themselves permission to make a really big difference.

Q: What if you’re not a leader, and what if you work with people who are very comfortable with old patterns? What role can you play in the “everyone a changemaker” world?

Well, if you help, say, a hotel company be the first changemaker company, it’s going to see many opportunities to create value and to do it efficiently. All the people in that hotel company are not mindless doormen and cooks and chambermaids; they are changemakers. They can see something that travelers or non-travelers need, and they can develop it. Well, of course, that hotel company will completely out-compete the others. So anyone can contribute by helping their organization change.

And anyone can contribute as a parent. If you’ve got a 15-year-old in your life that you care about, what would you do if she failed at math? You know you’d do something. If you’re good at math -- a tiny minority -- you might help directly. More commonly, you’ll think of bringing in a tutor or something like that.

What would you do if she was not practicing changemaking? Well, you probably wouldn’t even notice. But actually, once you realize that is the most important thing that she should be doing now -- because in a world defined by change, where is she going to be if she doesn’t have that skill in 10 or 15 years, when she’s 30? -- as a parent, you’re going to feel awfully bad if you didn’t help your daughter get that skill.

So what do you have to do? You don’t have to change the whole system. You can start right there with her. She says, “Dad, Mom, the way this park is run is a mess,” or, “The school is doing a terrible job with these immigrant children; they don’t understand English.” Whatever it is, when your daughter says, “This is a mess,” as a parent, you can say, “Oh, well why don’t you get your friends together and go and fix it?” “Who me?” “Yes, you! Why not?” Any parent can do that.

Why shouldn’t we encourage kids to start things? Whenever they see a problem or something that could be better, why don’t we make it really easy instead of really difficult?

Q: Why invest in young people? Why should leaders take a chance on someone who is untested or inexperienced?

With all due respect, there may be much less risk with young people who have not learned that they can’t do things than with the older person who never learned that they could have.

America will be Detroit and not Silicon Valley within 10 or 15 years if we don’t radically increase the proportion of young people who are changemakers -- and who are changemakers way before they turn 21. You don’t learn this by a book. You’ve got to get on the bicycle and ride. You’ve got to practice, practice, practice being powerful and being a changemaker. Once you know that and once you have the skills, you’ll learn whatever you have to learn. You have the key to the universe and to being a good person.

Q: What role should institutions, particularly religious institutions, play in the “everyone a changemaker” world?

The half-life of knowledge is getting shorter and shorter. I was just told by the dean of a very good technical school in India that they have discovered that half of what they taught in the first year is obsolete by the time the students are in the fourth year.

But this set of [changemaker] skills is never obsolete. This is the foundational set of skills. And parenthetically, the foundation of the foundation is the skill of empathy, of being a good person. This is where we really need religious institutions to do what they did at the time of the great prophets.

Now we’re going through a transition period that’s just as significant but much faster. This is the time when everyone has to have that skill of empathy, and everyone has to have that skill at a higher and higher and higher level.

The religious houses that contribute to this, that understand it, and that make sure that every parishioner -- that everyone that they touch -- has this skill, and that explain the ethical urgency of it in terms of equity and equality within society, will be vibrant.

How can we be training young people to be ready for confirmation or bar mitzvah or whatever it is if they don’t have this skill? You can’t be an adult in the world we’re living in if you don’t have the ability to be a good person.