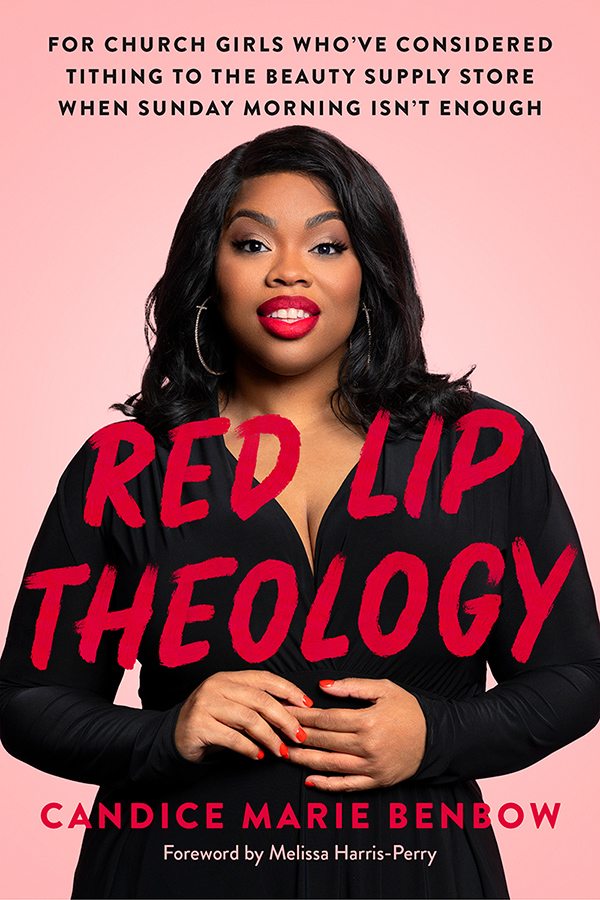

Candice Marie Benbow is explaining how “Red Lip Theology” came to be the title of her newly released first book.

The title encompasses her time at Duke Divinity School, including the discomfort many of her white classmates experienced in required Black church studies classes, her upbringing that interwove church, culture and womanism, and her love of red lipstick.

Ultimately, the title stems from her inability to suffer foolishness lightly when a classmate insists on a conversation in the seminary library by asking, “Do you consider yourself a black theologian or are you a regular theologian?”

His assumption that the former was a niche category and the latter the norm prompted her frustrated response.

“I could have gone off, but he wasn’t going to care,” she recalled recently. “I was just being smart and said, ‘I’m a red lip theologian,’ because I had red lipstick on that day. It’s wild because when I said it, it made all the sense in the world to me.”

She was giving language to her experience, she says.

“Red lip theology is the way through which I understand myself and I see the world and I understand my relationship with God and God’s relationship with me and everyone else, as a Black woman and a woman of faith,” she says.

“It gives the space for the nuance that I believe our faith has that we have to honor and cultivate, and it gives the room to a freedom for me to be human, which is the only thing I have ever been asked to be by God.”

In her book, Benbow writes about the Black church, theology and theological education and about the ways all have treated Black women. She also is candid about her late mother's legacy, her mental health and her sexual assault, the latter two topics taboo in some faith settings.

She spoke in December with Faith & Leadership’s Aleta Payne. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: Your mom is present throughout your book, across all topics. You do a beautiful job of painting your relationship. Could you talk a bit about an area you sometimes disagreed on, and that was faith?

Candice Marie Benbow: I did not set out to write about my mother when I was thinking about this book, but the more I wrote about faith and God, the more I was also writing about my mother.

I don’t come to the faith nor do I come to a relationship with God without her. She introduced me to faith. She introduced me to this loving and gracious God, and I had to learn this God anew and all over again when I lost her.

I could not have this conversation or have a conversation about God and Black women without also talking about motherhood and mothers because I also think the relationship that Black women, particularly Black church women, have with their mothers will always be one of the most difficult that we navigate.

There’s this tension of wanting to be the daughter that they want while also working toward the woman you’re becoming. That was always evident in our conversations around God and theology.

I would get so frustrated because my mother would always tell me the most beautiful thing that you can ever do is speak for yourself and ask questions and never accept answers at face value but, through good diligence, to be studied and astute and ask the right questions and challenge answers that seem insufficient.

I used to say that she needed to put an asterisk there for “except when I come to church” because she would always be frustrated when I would apply those things theologically. I understand because, unfortunately, any time we ask questions about or critique systems of church it is felt as though we’re critiquing the very people who introduced us to the faith or the very people who brought us up in church; that’s not necessarily the case.

But also there’s the truth that as Black women who have always been the forerunners of the church, it almost feels as though, “Who are you, little girl, to come and tell me and to challenge what I’ve thought and believed, what so many women before me have thought and believed as well?”

We didn’t see eye to eye about a lot of things theologically, but what I will always treasure is when she ordered two tubes of MAC Ruby Woo [lipstick] for me and for her.

That was her way of telling me that she understood me and that I was also doing something for her, too. My mother didn’t wear red lipstick at all, and so for her to have a tube was major, and it was the ultimate cosign.

Even if she’s like, “I don’t agree with 98% of what you say,” I believe she probably still would say that she supported me in that way. I hope that what the book did and does is honor that about us.

I hope the book honors that a loving relationship and an amazing mother-daughter relationship can still have tension and that the best of parents don’t always get it right, but the best of them give their children room to really bloom however they want to.

That “Red Lip Theology” is a book is a testament that even when my mother didn’t agree with me and thought differently from me, she still gave me room to grow and become who I believed was true enough for me. I know a lot of children, even when they’re adults, who can’t say that about their relationship with their parents.

I’m pretty sure she was cringing the whole time I wrote the essay on sex. But she also gave me the room to really become, to live into who even she believed I had been called to be, and she didn’t try to squelch that. I think that that’s one of the greatest gifts that she could have ever given me.

F&L: You write powerfully about God’s love for us and that God’s priority for us is our being happy and well. That feels foundational to a lot of what you say in the book. I’m wondering what would that countercultural theological embrace look like to you if we all moved into that place?

CMB: When I think about what a world looks like where we lean fully into what is whole and well and a world of joy for us that I truly believe God wants for us, it’s nothing like we’ve ever seen.

The truth is that we know what a world with more sorrow looks like. We’ve seen so much of it. We’ve seen what happens when people lean into the desperation of insecurities and evil, but when we see these glimpses of joy when people fully believe that they can flourish and that it’s God’s intention and design for them to flourish, those moments, we’re like, “Yeah, give me more of that.”

I hope that it’s seen in my lifetime. I think that we get glimpses of it. I think we’re getting more and more glimpses of it, and I hope that we continue to find ways to push that truth.

I had to walk away from theology that suggested God wanted me broken, that being broken is my permanent state. God made me whole and God wants me whole and God wants me well.

That doesn’t mean that the difficult times don’t come because they do, but I think that there’s something fundamentally flawed about us believing that our posture with God has to always be one of brokenness.

I think that’s how we try to make sense of pain in the world, and we try to make sense of it in ways that we don’t need to. God wants me thriving, and I can see that and be that in my lifetime and so can everybody else. I think we shift to that kind of posture when we hit a hard time.

The question always becomes, how do I move through them and learn from them in a way that gives me back to that place, to that happy wholeness inside because that’s where I’m always supposed to be? So when the time comes, how do we move back there?

I think we haven’t seen it, but that gives us even more generativity to make it happen.

F&L: You are willing to critique others but also yourself. I’m wondering what others might learn from your willingness to name what is broken versus what is healthy even if what is healthy is something that makes people uncomfortable. What can people learn when, particularly sometimes in church culture, candor is not what is expected?

CMB: My truth has been that I’ve made some really unhealthy decisions, rooted in a lot of different things. Some of those decisions I made knowingly, and some of them I made with the best of intentions that it would look differently, and the outcomes were not favorable for me.

Yet God’s grace was sufficient and allowed me to move through them and grow from them and thrive and not look like at all what I’ve been through.

I tell that truth because I know that I’m not the only person who has done something dumb, and I also know what the weight of shame and the weight of guilt can do to you, especially if you’re churched and you continue to have the “You know better” running around in your head.

And then it goes and moves from “You know better” to “Why did I do this? I can’t believe I did this.” You may get stuck there because you’re paralyzed by the decision you made, the outcome of that decision.

I can tell you that when you give yourself room to be human, when you give yourself room to accept responsibility and accountability for your actions and face yourself and decide, “I’ve got to figure out why I did this and then I’ve got to work to make a different decision,” when you do that, you find how amazing God’s grace is and the capacity for you to be able to move differently and evolve in ways that I just honestly don’t think you can if you don’t tell the truth.

I also know that it’s hard to tell the truth. It’s hard to be that vulnerable, and it’s hard to be that transparent. Maybe everybody won’t be, but maybe you will read me being that transparent, and it may allow you to be transparent in your journal, and it may allow you to be transparent in your prayers because sometimes we go to God and we lie to God, too.

Maybe it will give you the space to say, “I’m going to tell the truth to myself, and in telling the truth to myself then I’m going to allow myself to be open to the possibilities the truth-telling can bring.”

F&L: You talk about mental health and sexual assault, which are both topics that often aren’t talked about in healthy, honest ways, especially in some churches. Are there ways that you are modeling something, particularly for communities where those sorts of things are bottled up?

CMB: I hope that it creates more room for us to sit with the weight of those experiences and not try to find ways to shout through those experiences.

There was nothing that I could shout about when I was in a mental health hospital. There was nothing that I could shout about when I’m sitting in this hospital and I cannot go home because the doctors are not sure that if I go home that I’m not going to end my life, and I wasn’t sure, either.

I could not shout about that. I could not.

There were Scriptures that I could quote, but quoting those Scriptures didn’t radically change those circumstances. I was still in the hospital, and I had to do some serious work myself and with my therapist and a team to be better.

I could not shout the memory. There wasn’t enough shouting that I could do to shout away the memory of lying on my floor and trying to crawl to my door because I just could not move because of what had just happened to me.

Again, there were words, there were Scriptures that I could shout, but they would have been woefully insufficient to the reality of my experience.

To hear people say things like, “You’ve got to forgive. The forgiveness isn’t for the other person. It’s for you.” You’re not going to convince me that God requires that I forgive the man who raped me in order to heal me.

I had to spend a lot of time getting really quiet and being like, “What do I know to be true about God? And if I’m human, I’m human, and I don’t think God cares whether or not I forgive my rapist.”

I do think that there are people whom I am in relationship with that if they apologize to me, and I care deeply about the relationship and I choose not to extend forgiveness when they’ve wronged me, I do think that those are times when God is going to look at me and be like, “Now what’s that about?”

So, I hold to that because that’s what it means to be in community with people, and so I hope that this creates different kinds of conversation.

Because I’m not a preacher, because I’m a theologian and my work focuses around thinking about God in these kinds of ways, it requires a different tension, and so I do think very often that gives me a little more room to say, “Hey, we’ve got to really think differently about how we talk about mental health. We’ve got to think differently about how we talk about sexual assault.”

When I work with pastors on making their sermons and their Bible studies much more culturally competent and respectful, I’m always asking them when they are reading a sermon, “Explain to me how that’ll work if I’ve been raped. Explain to me how that’ll work if my father molested me.”

They look at me like, “Huh, I never thought about that.” Think about it. Because it has to work for all of us.

The gospel isn’t just cherry-picked for certain folks. It’s got to work for all of us and I pray that this is a space where the very people who have felt like the church has ignored them or not necessarily cared about their experiences, I pray that these become moments where they feel like, “Somebody is listening to me and they care about me and I’m not alone.”

I hope in that same vein pastors are like, “All right, we need to think about this differently. We need to think about how our preaching and our teaching affects people who are on the underside of some horrific experiences,” because, again, it’s got to work for all of us.

If it doesn’t work for all of us, then it doesn’t work.