To find the church that is widely credited with having started the environmental justice movement, you take I-85 to Warren County, on North Carolina’s northern border. You get off at Exit 215 and meander along two-lane roads lined with farms, vacant fields, old barns and abundant hay bales until you arrive at Coley Springs Missionary Baptist Church.

This church’s tenacious opposition to a landfill 40 years ago laid the foundation for books, protests, college courses and, most recently, a new office created by the Biden administration. When EPA Administrator Michael S. Regan announced the creation of the Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights in September 2022, he traveled to Warren County to do so. In a ceremony at the county courthouse, Regan lauded local efforts to call attention to poor communities being dumped upon, citing the citizens’ “heroism.”

Sitting lonesome next to a field and across from a cemetery, Coley Springs MBC is far from a physically imposing megachurch. The rectangular brick building with stained-glass windows holds 15 rows of wooden pews with a capacity of 450, but far fewer than that show up for services, especially since the pandemic. There is just enough room for an organ and a set of drums on the side.

Is it surprising that a small country church sparked a widespread movement?

“Not at all,” said the Rev. Carson Jones, the pastor of Coley Springs. “It’s in the tradition of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, where Dr. King preached, and the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, where the civil rights movement began. … We’re building on that tradition at Coley Springs as a community seeking justice.”

The church’s membership is almost entirely Black.

Extraordinary circumstances led to the protest, said the Rev. Bill Kearney, the assistant pastor who leads the church’s ongoing environmental and health improvement efforts. “People said, ‘I don’t normally do this, but I’ve got to take a stand,’” Kearney said.

The story has been recounted many times over the years by journalists and historians. According to a case study published by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, it all began back in 1976 when the Raleigh-based Ward Transformer Company was looking to get rid of a warehouse full of oil tainted with PCBs, a group of cancer-causing chemicals that had been recently banned by the federal government.

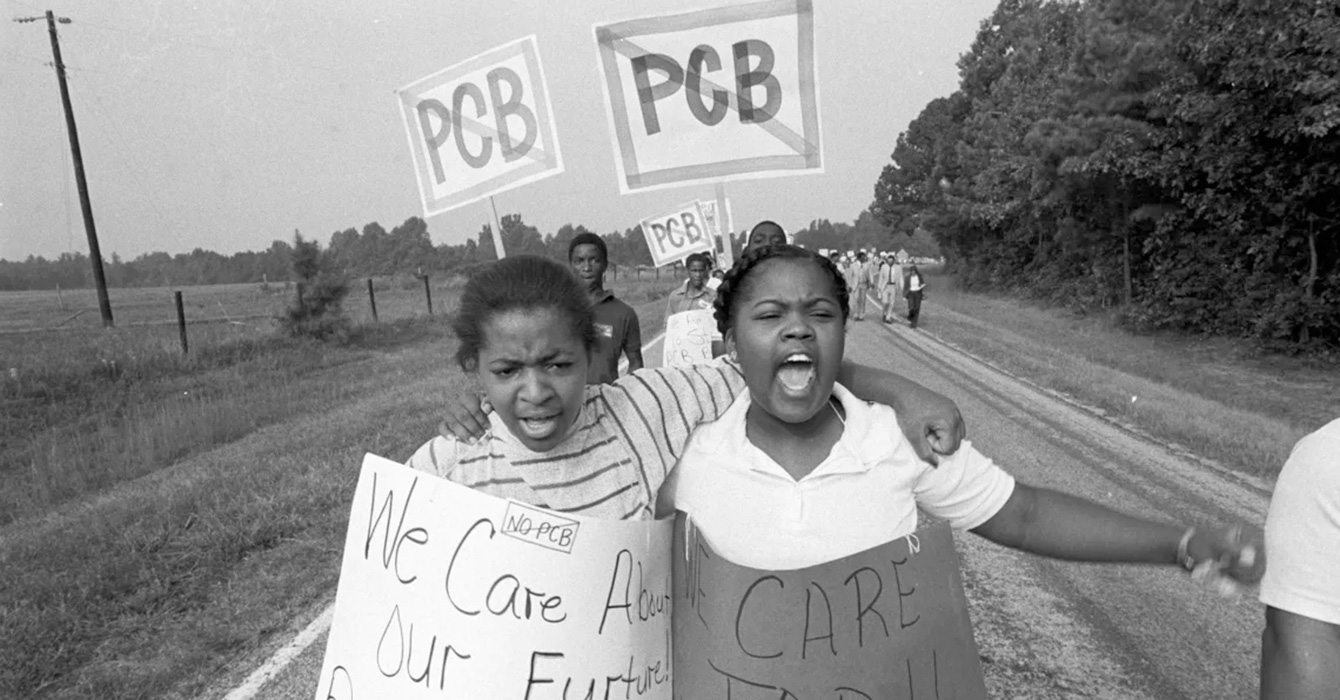

Ward hired a New York trucking company to dispose of the oil. That company sprayed 31,000 gallons along approximately 240 miles of rural roads in 14 North Carolina counties.

The scheme was soon uncovered, and executives of both companies eventually served prison terms, but that didn’t solve the tainted-soil problem that remained. After much deliberation and controversy, the state chose to build a landfill in Warren County and dump it there. The landfill site was in Afton, a community about 2 1/2 miles from the church.

Residents of Warren County believed then — and still believe — that state officials chose their county for the landfill thinking it would be an easy target. Once one of the wealthiest counties in North Carolina when the economy ran on slavery, by 1982 Warren had dropped to one of the poorest as agriculture slowly declined.

“They depended on there not being any real pushback,” Kearney said. “Warren County had no political clout, so they expected no real opposition.”

If that was part of the state’s thinking, it was a miscalculation; they had plenty of opposition from one woman alone — Dollie Burwell. Although she demurs at taking sole credit, Burwell is widely considered the spark that ignited opposition to the state’s plans. A community activist at the time, she had participated in civil rights protests and educational programs across the nation and even overseas.

Burwell — who lived 3 1/2 miles from the landfill site — had passion and, more importantly, contacts. She enlisted big names into the fight, like the Rev. Leon White, field director for the United Church of Christ Racial Justice Commission, and Ben Chavis, a prominent civil rights activist who had been part of the much-publicized Wilmington 10 civil rights controversy.

“I knew that toxic waste was not good for the community,” Burwell said in a recent interview. “What they were doing to the environment was unjust, and what they were doing to the people was unjust.”

The church hardly fought the battle alone; it was more the base of operations where a wide swath of the community came together with church members. (In fact, Burwell, though a frequent visitor to Coley Springs, was not a member herself.)

The fight united the county’s residents across racial lines, bringing out white people like Wayne Moseley, an educator who was living in Raleigh at the time but had grown up in Warren County.

He agreed to take part in the protest because he had known Burwell for many years — in a small community, “you knew everybody,” he explained — and because his mother still lived there.

He remembers the day — Sept. 15, 1982. “We met at Coley Springs Baptist Church that morning. That was probably one of the few times I had even known whites and Blacks and people of color to ever march arm-in-arm, hand-in-hand and sing out of the same hymnals. And it was one of the only times white people had set foot in a Black church. … We marched roughly 2 miles down to the dump site. There were maybe 75 highway patrol officers in full force with riot gear and shields and batons in hand.”

Moseley remembers a highway patrol commander saying, “‘You are in violation of the law. … I have orders from the governor.’ But White raised his hand and pointed to the sky and said, ‘I get my orders from the man above.’”

Moseley was arrested, along with more than 400 others over the course of six weeks of protests. Ultimately, they were not able to prevent the landfill.

Still, no one connected with the protests considers the efforts futile. The landfill eventually was closed down and cleaned up. In addition, the efforts generated nationwide publicity highlighting the tendency to locate hazardous and undesirable facilities disproportionately in poor communities — especially communities of color.

Burwell said she was excited when Regan, the EPA head, chose to come to Warren County last fall to announce the launch of the Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights.

“What happened in 1982 was an injustice to the environment, but it was also a civil rights injustice. Mr. Regan understood that, and this administration understood that,” she said.

At Coley Springs, the protests sparked efforts aimed at continuous improvements in the church and in the community. Kearney, the assistant pastor, was actually a police officer in Washington, D.C., back then; he said he felt God calling him to return to Warren County, where he grew up.

Today, he leads the Warren County Environmental Action Team, which is concerned with such matters as access to healthy food, access to health care and “helping the community voice to be heard,” he said.

“Environmental justice is part of a larger inequity of resources that has a historical basis,” Kearney said. Among other goals, the team wants to generate studies of the long-term health effects of the closed landfill.

The county still suffers from economic and social challenges, including ingrained problems such as too many residents who do not have healthy diets, Kearney said. Among the church’s programs is the Harvest of Hope Garden on land behind the church, which provides fresh vegetables to church members.

“Jesus said it’s right to live abundant lives, and that means leading healthy lives — healthy in body, mind and spirit,” Kearney said.

“We have gotten the attention of the EPA,” he said. “Moving forward, how can we develop a framework so we can tap into resources? … The faith community has to help build provisions for change. You have to pray, but you have to put feet on that prayer.”

Evoking the biblical story of Joshua exploring the promised land for the Israelites and reporting back to Moses that although there were giants in the land, they could be conquered with God’s help, Kearney said: “We need to build a bolder vision and not be afraid of the giants, because God has already given us the land. What man meant for harm, God meant for good.”