This week at Faith & Leadership Fuller Seminary President Richard Mouw has a short essay on the merits of engaging both high and low culture, while still holding a distinction between them -- a distinction between, say, the literary feats of Truman Capote and the old crime pulps of Mickey Spillane.

While there are those who might dispute the high vs. low distinction (the guys who run this blog, or most of the hipsters in Brooklyn), that’s not really the point to get hung up on.

Here’s the more interesting takeaway: Mouw’s essay holds up a skill that Christians leading a church, an organization or a school need: the ability to hold divergent entities -- whether they are ideas or stances on a hot issue or aesthetic tastes -- not in opposition but in healthy tension. Social innovation author Roger Martin calls this “opposable thinking,” a mindset, he thinks, has historically led to compelling cultural achievements in business, education and the arts.

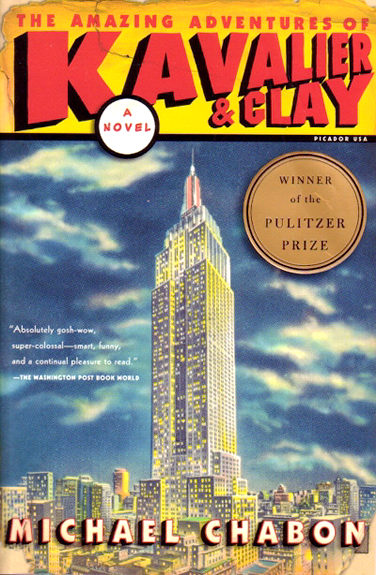

Mouw’s point brings to mind the distinct style of novelist Michael Chabon. Chabon is largely responsible for reviving genre fiction in high-brow literary circles, with novels like “The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay,” “The Yiddish Policeman’s Union,” or his latest novel “Telegraph Avenue” (perhaps not as well received). He draws from the best of what genre fiction (crime noir, graphic novels, sci-fi) offers, and incorporates it into the subtle character development and rich social commentary of literary fiction.

The thing is, Chabon won the Pulitzer for “Kavalier and Clay” -- certainly a “high” literary achievement. Perhaps this is Mouw’s point. The greatest cultural goods (and in particular the cultural goods that Christians produce) exemplify this kind of opposable creativity.

It’s worth asking then, what are other models, whether in the arts or in another social sector, of this kind of creative thinking? What can Christians learn from them? And how can Christians find ways to practice them in service to churches and communities, organizations and schools?

Mouw gets us thinking about that.

Arts

Discuss: Richard Mouw on high and low culture

Michael Chabon, Truman Capote and why healthy tensions create cultural goods.