Along with the pandemic came public calls to maintain proper practices of hand washing, but in the history of medicine, the importance of sanitation wasn’t always assumed.

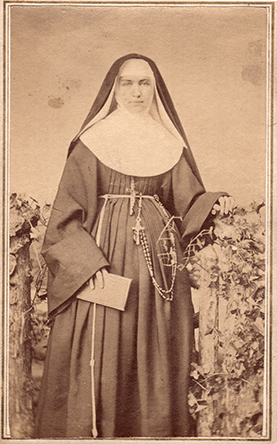

One of the earliest proponents of hand washing in the United States was a German-born Franciscan nun living in upstate New York named Marianne Cope. In 2012, she was canonized by Pope Benedict XVI, but despite this recognition from the Catholic Church, she remains an overlooked figure in America’s medical history.

Here’s a look back at the role Cope played in establishing this crucial public health measure, and how her faith was the driving force behind her work.

Compassion, empathy and sanitation

About a year after Cope was born, her family emigrated from Germany to Utica, New York, where they joined the city’s growing immigrant community. Her teenage years involved taking care of her younger brothers and sisters, as well as overseeing her family’s finances after her father fell ill. So impressed was the young Cope with the in-home nursing provided to him by the local Sisters of St. Francis that after her father’s death in 1862, she joined the Sisters of St. Francis in nearby Syracuse.

After first working as a teacher, Cope went on to serve as the superintendent of the convent. In her new role, she was involved with opening two hospitals as alternatives to the sisters caring for the sick in their own homes.

The first, St. Elizabeth Hospital in Utica, opened in 1866, followed three years later by St. Joseph’s Hospital in Syracuse. Cope served as the head administrator of St. Joseph’s -- the city’s first public hospital -- for six of its first seven years.

Using the life of St. Francis of Assisi as a model, the sisters focused on caring for the poor -- specifically, through providing education and health care to those who needed it most. In line with this practice, the sisters chose a spot on Prospect Hill, an economically disadvantaged neighborhood of north Syracuse, as the location for their hospital. They purchased two buildings -- a saloon and a dance hall -- and erected a new building between them, forming St. Joseph’s Hospital.

“The people in this area were not being cared for,” said Kristin Barrett-Anderson, the director of the St. Marianne Cope Shrine & Museum in Syracuse. “One line in St. Joseph’s charter of incorporation was ‘to care for every person equally, no matter race, religion, economic means or illness.’” This included people with mental illness, those living with drug or alcohol addiction, unwed mothers and other groups who were refused care in hospitals at the time, as well as those who were unable to pay.

In addition to her dedication to caring for the sick, Cope, who took over as the hospital administrator a few months after St. Joseph’s opened, innovated and improved the medical care.

She implemented a series of sanitation and hygiene policies to help prevent the spread of illness, not only requiring the doctors and nurses to adopt them at a time when they were not part of medical training but wholeheartedly practicing them herself -- getting down on her hands and knees to wash the floors, for example -- to demonstrate her belief in and commitment to hygienic care.

Cope carefully instructed doctors and nurses on the most effective methods of hand washing and why it was so important to repeat between patients. She also explained how hygiene went beyond simply washing hands to frequently changing gowns and aprons and thoroughly sanitizing medical equipment. Finally, she emphasized the importance of sanitation in other aspects of the hospital’s functioning, such as washing patients’ bandages and bedsheets and thoroughly cleaning their rooms, including the floors, walls and furniture.

From the spotless patient rooms to the distinctive smell of carbolic acid (an early antiseptic) in the hallways, it was quickly evident to those entering St. Joseph’s that Cope was running a tight but compassionate ship.

Though Cope had no formal medical training, her dedication to embodying the Franciscan values of compassion, self-sacrifice, devotion, courage and service inspired her to constantly seek out the latest scientific and medical breakthroughs so that she and her sisters could provide the best possible care at St. Joseph’s.

“Her faith drove her,” Barrett-Anderson said. “She knew what the patients needed.”

And as it turned out, Cope’s cultural background also played a role in her self-education. In the late 19th century, Germany was one of the world’s leaders in medical research, including major contributions in areas involving the cause, spread and prevention of infectious disease. Cope was able to gain access to -- and understand -- these research papers thanks to the flow of information between Germany and the immigrant community in the area.

At that point, it was not yet known precisely why hospitals in Europe that implemented sanitation techniques like hand washing had lower death rates. But when Cope read about these promising practices -- as well as advancements in medical equipment and sanitation tools -- she saw them as ways to better serve the patients of St. Joseph’s and provide them with more compassionate care.

While others remained skeptical about how such innovations could possibly save lives, for Cope, this was simply an extension of her faith. She understood that science improved the care that her faith drove her to offer.

Given that preventive hand washing and other sanitation strategies were not standard medical practice in the U.S. at the time, Cope had to convince the rest of the hospital staff to comply. According to Barrett-Anderson, Cope’s signature leadership style -- a combination of compassion, strictness and diplomacy -- ensured that her policies were fully adopted.

“The way she phrased things, you couldn’t say no,” Barrett-Anderson said. “You couldn’t take anything personally, because she was so kind. And here she is, a woman in the 1800s, and she’s telling these men what to do. All these doctors who are used to being in charge? She was in charge of them.”

The next calling

After seven years at St. Joseph’s, Cope left the hospital in 1877 when she was elected provincial superior of the Syracuse-area Franciscan congregations. It was during that tenure, in 1883, that she received a letter from a priest representing the bishop in Hawaii, who was looking for volunteers to travel to the islands and care for the sick.

From the 50 religious communities to which the priest appealed in the United States and Canada, Cope was the only person to respond with an indication of interest. The priest traveled to Syracuse and met with Cope, finally disclosing that the work would involve caring for people with Hansen’s disease -- that is, leprosy. Despite being aware of the severity and stigma associated with the condition, Cope agreed to travel to Hawaii to establish a hospital there. A few months later, she made the long journey across the United States by rail and then to the islands by ship with six of her fellow sisters.

At the time, it was widely thought that Hansen’s disease was highly contagious (though we now know otherwise), so Cope and the sisters immediately implemented as many of the sanitation practices from St. Joseph’s as possible. Their first act upon arrival was to thoroughly clean and sanitize the clinic.

“They literally scrubbed the whole place down, washed the sheets and linens and aired out the facility,” said Mary Stronach, who along with her husband Robert serves on the board of the Oneida County History Center, where they are the resident experts on Cope. “Then they went a little further, planting flowers. They really tried to establish a sense of joy and brotherhood and sisterhood among those people who were suffering as lepers and who had been marginalized.”

Cope and the sisters came to Hawaii to care for people with Hansen’s disease, not to act as missionaries. In fact, not only did they permit patients to retain their culture and language, but Cope and her colleagues embraced Indigenous Hawaiian customs and learned the local language themselves so they would be able to communicate with the patients, Barrett-Anderson said.

This stands in stark contrast to many other American and Canadian religious orders, who set out to “help” Indigenous communities by converting them to Christianity and subverting their native cultures in the process.

“One of the sisters’ key values is being present to the moment and being present to whoever you are in front of, meeting them where they are,” Barrett-Anderson said. “So if they’re giving equal care and they’re there for the sake of the patient, it’s not just the health care; it’s being there for them, mind, body and spirit.”

Cope’s legacy continues

Now, more than a century after her death, Cope’s presence remains strong in upstate New York. Both St. Elizabeth and St. Joseph’s hospitals are still in operation today. A Utica soup kitchen bearing Cope’s name and utilizing her sanitation protocol has remained open throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. The Syracuse University College of Medicine -- where Cope initiated a training program for medical students -- now operates as SUNY Upstate Medical University and continues to advance medicine through research, including a COVID-19 antibody clinical trial.

“She’s known as ‘Utica’s saint,’” Robert Stronach said, noting that the city has recently put up signs welcoming people to the home of St. Marianne Cope.

Those aware of Cope’s story today tend to be most familiar with the portion that begins with her arrival in Hawaii, ultimately ending with her sainthood. But not as many know about the contributions to health care and sanitation she made prior to leaving upstate New York. As we look back on the history of public health in America -- and particularly as we live through a historic health crisis of our own -- there has never been a more relevant time to recognize Cope’s contributions to the field and to practice her faith-inspired empathetic approach to health care.

For Cope, having an understanding of science and medicine helped her carry out and truly live the Franciscan values. When she faced challenges caring for the sick, whether in Syracuse or in Hawaii, her faith in both God and science equipped her to provide effective and compassionate care -- with dignity -- for those who needed it most.