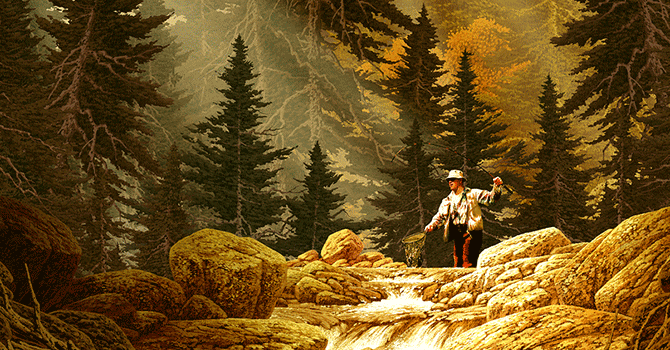

Stepping into the river feels like coming home. The murmur of the water as it dances through a rapid, the early-morning sun walking down the mountain on the far side of the valley, the aspen leaves shimmering like a million green prisms, the worn cork fly-rod handle in my right hand, the biting cold water swirling around my ankles -- this is the most familiar place I have ever known.

I begin to cast. Wide loops of line float silently above me, with a fly no larger than a fingernail attached to the end. Watching my caddisfly dimple the surface as it lands, I lean forward, tenderly pinching the line between my thumb and forefinger, and pause in wonder at this moment that shimmers with possibility.

As a child, I spent many summers in Colorado on this stretch of river some 60 miles from any ski resort and a mile up a mountain road to nowhere. I caught my first trout on a bumblebee pattern only a few miles upriver. My cousin and I once netted 102 trout in a day on a nearby mountain stream.

While I’ve grown and traveled for studies, work and “adult” life, my imagination regularly transports me back to this small stretch of water. In every case, the river and craft of fly fishing always return more to me than I bring to them.

Today, in the communities I serve and the religious organizations I study, the craft of fly fishing and the experience of wading in these (and similar) waters offer four insights about the practice of religious leadership.

Go together whenever possible, but also be willing to go alone. My family abided by an unspoken truth on the river: it is always better to fish together. Companions not only provide company but also can help each other land fish, relieve snags and offer extra pairs of attentive eyes. Even though we always each carried a rod, we frequently fished only a single line.

The craft of fly fishing also requires solitary moments with just the water, a rod and a fly. In these quiet, unaccompanied moments, I have often probed the hard-to-get-to pockets of water or learned how to tie a particular knot or make a certain cast on my own. I can silently test the deep waters of my own soul.

There is an African proverb that says, “Alone we can go fast, but together we can go far.” Similarly, the practice of religious leadership is better when sustained by a broader community and good company. Indeed, religious leadership frequently feels like a “peerless vocation” -- as one college president recently shared with me -- but faith-filled ways of leadership do not exist apart from strong networks of Christian leaders and the self-assurance and courage that come from also exploring the deep waters of our communities and inner lives alone.

Learn to move delicately and swiftly. Navigating riverbanks and rocky river bottoms requires careful movements. The next step is often unseeable, and the geography of river bottoms can change unexpectedly. On more than one occasion, I have slipped into the water, fallen directly on my back and baptized technology in unpredictable currents. Confidence and ease while wading comes with time, but attending closely to the movement and feel of the water helps.

At the same time, the activity above the water requires swift and decisive movements. A swift backward movement of the wrist begins building the energy for each cast, which is then compounded by a well-timed reversal of the motion. Once the fly has landed on the water, strikes from lurking trout pass in an instant and are readily missed if the fisher is inattentive or the response too slow or mistimed.

The craft of religious leadership requires a similar combination of delicate ease and swift, appropriately timed activity. The social geography of many religious communities is more complicated than the rivers I’ve explored. The combination of often-unseen aspects of a community and forces of change beyond any single individual’s control require wading with delicate care.

A single moment or encounter can decisively alter an individual’s sense of vocation and relationship to a community. Giving a well-timed word of encouragement, speaking someone’s name, acknowledging responsibility for an error and similar actions strengthen the social fabric that is integral to Christian institutional life. In some cases, those who lead organizations have only hours or even moments to determine a response to an unexpected event, tragedy or conflict. In every case, the timeliness, appropriateness and form of action may shape a community for weeks, months and years to come.

Explore both the surface and the depths. Fly fishing utilizes two primary approaches to enticing unsuspecting fish: presenting a “dry” fly that sits on top of the water or casting a “wet” fly that sinks below the surface. Raised on an exclusively dry-fly fishing diet, I did not develop until much later the ability to fish below the surface and explore the river’s depths.

Religious leadership requires attention to both the surface and the subsurface dimensions of communities. Although a considerable amount of activity exists on the surface of Christian institutions -- and it is important to attend to the visible expressions of an organization and community -- a significant amount of the organizational life occurs in places that cannot be seen. Learning to understand, explore and nurture the subsurface dimensions of organizational religious life can support the visible and public dimensions of the community.

Untangle knots from both ends. Invariably, things do not go as planned in fly fishing. The combination of a very fine line, tiny hooks covered with fur and feathers, and a form of casting that is part circus act and part art creates optimal conditions for hairball-size knots when things go awry. On some days, I spend just as much time untangling knots as I do having my line in the water.

The various forms of dysfunction and “knottiness” of organized religious life don’t need to be rehearsed here. Much like untangling knots on the river, however, resolving the most complex knots in religious communities can be accomplished only by working from both ends. In many cases, untangling the wicked problems that plague communities will take considerable time and extra pairs of hands (remember, go with others whenever possible). Much as the most patient fly fishers notice snags before they lead to knotted lines, attentive leaders and alert companions identify tangles within communities before they turn into greater trouble.