Familiar Bible stories can be some of the hardest to read as adults. The children’s Sunday school versions, with their accompanying crafts and upbeat sing-alongs, can obscure the full range of nuance and complexity in a given passage. Take the parable of the sower from Matthew 13.

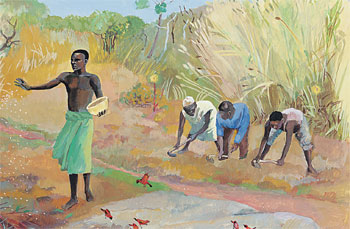

In all the illustrations I’ve seen, the sun is out, the sower happily scattering seeds over an artfully textured ground. Given the bounty in the “good soil” harvest, the seeds that aren’t so lucky don’t seem to matter. The classroom drawings never fully capture the scope of loss present in the story — the seeds pulverized in the bird’s beak, withered by the sun among the rocks, strangled by the weeds.

Suddenly, this cheery parable fills me with discomfort. Why wasn’t the sower more careful? Surely there are ways she might have minimized the risk and maximized the yield.

I feel frustrated that the sower seems entirely unconcerned about failure. As she walks, she tosses handfuls of seeds to fall where they will. Some will grow; most will not. No attention is given to the soil quality. The sower simply keeps on sowing.

I’ve realized that this reading is challenging me to reconsider the parable’s lesson. Perhaps this story is more about consistent faithfulness and less about engineering results. But that is not what I want to hear in a moment of great change and uncertainty for the mainline church in America.

Congregations are aging. Membership numbers are declining. Churches are closing their doors and selling their properties at an unprecedented rate. This does not seem like the moment to be scattering our limited precious seeds with abandon.

And yet what if this is the exact right moment for the church to be taking risks and embracing failure?

Jeremy Utley and Perry Klebahn lead and teach at Stanford’s Hasso Plattner Institute of Design. They help organizations innovate in a rapidly changing world by cultivating cultures of experimentation — what, for the church, could be seen as the spiritual disciplines of listening, humility, courage and holy playfulness all rolled into one.

In their book “Ideaflow,” they write, “What are the chances you’ll make an interesting discovery doing something in the exact same way you always have?”

I wonder what this imagination might do for the church. If doing what we always have is no longer working, could this be the moment to experiment and try something new? Sometimes an experiment will produce 30 times what was sown. Sometimes an experiment will fail. Often it takes many failures before a successful solution is found. Recall the story of the light bulb.

I believe failure is essential for vibrant congregations. But failing is scary. In order to survive, the church must create a culture where failure is expected, welcomed and even celebrated.

Utley and Klebahn offer some suggestions on creating this kind of culture.

First, individuals and groups need to feel a sense of safety in order to take risks. When we’re afraid that we’ll fail — or that we or our ideas will be judged, laughed at or dismissed — our creative ability withers. Our brains (and that infamous entity called the church committee) are masters at naming why new ideas won’t work. While this instinct can keep us safe, it can also be wrong. We don’t always know where the good soil is. Scattering with abandon creates opportunities for learning and even surprise.

To scatter with abandon, shift the goal from finding “good” ideas to simply getting as many ideas out on paper as possible. Get playful. Bring snacks and colorful Post-it notes. Ask a middle schooler to join the conversation. Pull your chairs into a circle or move to a space with lots of light and big posters on the walls. At this stage, the goal is quantity over quality. The only rule is that ideas cannot be judged or deliberated.

Initially, ideas might come slowly and feel obvious. Keep going! One leader who uses the ideaflow process told Utley and Klebahn that it’s always excruciating for her — but only at the start. “As soon as she gives herself permission to write something truly outrageous, ridiculous or just plain illegal,” they write, “the floodgates open.”

Second, make space in the schedule to fail. Utley and Klebahn write, “To learn something new, you must try new things, and experiments always have a risk of failure. To take that kind of risk regularly, you can’t chase 99 percent efficiency every moment of your day.”

Not every new idea will bring in more young people or help balance the budget. But when framed with intention, every new idea is a learning opportunity for a congregation. Start talking about the congregation’s latest experiment and the learnings it produced, regardless of how well it achieved the anticipated results.

Utley and Klebahn note Thomas Edison’s response to a friend who lamented Edison’s lack of results on a project despite his hard work: “Results! Why, man, I have gotten a lot of results! I know several thousand things that won’t work.”

Not every project needs to be “the solution” as long as we are able to learn from it.

A few Sundays ago, I heard a pastor retell the parable of the sower and recount the harvest it produced as “thirty-, sixty- and even one hundredfold.” That’s how Mark 4 tells the story, but it’s not what Matthew says. Instead of saving the largest, most remarkable yield for the end, Matthew’s version says the yield was “in one case a hundredfold, in another sixty, and in another thirty” (Matthew 13:23 NRSVue) — concluding with the smallest. Even the smallest yield is worthy of note, Matthew seems to be saying.

Failure happens when we take risks. Our call is to be faithful sowers who scatter with abandon.

And yet what if this is the exact right moment for the church to be taking risks and embracing failure?