In 1995, I was 26 years old and beginning my Ph.D. in systematic theology at the University of Toronto. During one of my first courses in the early fall semester, I sat alone in the front of the lecture hall waiting for class to begin. There was a blank yellow notepad in front of me, along with three blue pens, lined up, waiting to be used.

As usual, I was early. I was thinking about what I was going to get for lunch that day, wondering whether I had any change at the bottom of my bag for a coffee, debating whether the new sweater I was wearing was too tight. Behind me, the door opened and closed, and the hurried traffic of a filling classroom thrummed in the increasingly warm, sunlit room.

The professor walked in, and as if to signal the beginning of class, a man’s voice behind me rang out, “Thank God! Another Asian!” Eyes turned toward me. I looked back and saw a small group of friends, young male Asian students, walking through the door. At first, I wondered whether I knew them from somewhere.

Then, feeling increasing attention, I imagined all the people in the room associating me with them in their minds, agreeing and acknowledging me as the “other Asian” and thus a natural part of their group. Being recognized as a peer, an inherent part of their tribe, a body contained under the shamed title of “Asian,” made me resent them deeply in that moment, and even more, made me resent myself.

It was not the first time I had been singled out in public for being Asian. I had grown up in what was then the very white community of London, Ontario, which still had a long way to go when it came to embracing minorities. I was accustomed to varying degrees of discrimination -- from being tokenized for my ethnicity outside my Asian community to being dismissed for my gender within it.

As I matured, the unquestionable magnetism I sensed that other Asians had with one another drove me to distance myself from them, isolating myself from the community that was supposed to be my own.

From the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 to the recent uptick in hate crimes during the coronavirus pandemic, the history of Asians in America has been one of violence, xenophobia, repression and assimilation. It has also been, to an extent far less appreciated, one of triumphant innovation and radicalism.

Asian Americans have always had a peculiar relationship with their own identity -- one that is vague and unsettled. Many of us have been raised with the indoctrinating principles of unbreakable loyalty to our families and to fulfill the warped promise of the American dream.

As a way of honoring their dogged sacrifices in our behalf, we have been taught to compete against one another, to work harder than all the rest, to earn the approval of white people in an attempt to gain our piece of success. We have been praised as a “model minority” for our diligence, our intellect and our amenability -- mostly, in service of demeaning other groups of people -- while also being trivialized through the hypersexualization of our women and the emasculation of our men.

But even before anyone else gets the opportunity to poke fun at us, we are often the first to reduce and satirize ourselves. I, like so many others, have always been caught in this fight for approval, acceptance and success, struggling against the contradiction of self-hatred and praise in the confusing trap of Asian American consciousness.

When I was called out as “another Asian” during that early Ph.D. class, I felt a dormant anxiety resurge. I was being seen in a room, and erased as a person.

While I am remorseful for my resentment in the moment, I must admit that a small part of me still harbors a seed of that feeling. Not against the man who spoke, or my being associated with the group of Asians, or even being racially differentiated, but against my being acknowledged purely because I was Asian -- being acknowledged only to be tokenized.

Although I am now known as an “Asian theologian” or a “Korean American theologian” -- I even regard myself in such a way -- I have constantly felt troubled by the idea of being a delegate for an entire ethnicity or race.

I feel both empowered and confined by the title that has followed me, and I wonder whether there will ever be a time when I will be known as simply a theologian, rather than the Asian American theologian. Then again, I wonder whether there will also be a time when I will not feel so unsettled about it.

The predicament for Asian Americans in the theological field -- and, more specifically, for Asian American women -- is that our work cannot be separated from our identity. This challenge is familiar to us, as it is to other ethnic minorities in the field, but it is not something that white theologians have to perpetually confront. On the one hand, I feel that I shouldn’t constantly have to address my racialized presence in my work.

But on the other hand, because there are not many of our voices represented in academia or in literature, I feel that I have an obligation, not just to address it, but to underscore it as a vital part of my legacy. This plight has always been fraught with tension. And for me, the galvanization of Asian identity has always proved more powerful.

Overall, my work as a theologian has some deeply meaningful rewards. I am given the opportunity to reflect and ponder on the notion of who God is. I have the privilege of trying to speak faithfully about God in a way that deepens the theological discourse, broadens the range of conversation partners and takes seriously the voices that have been absent from the table for the past 2,000 years. I hope that my theological imagination and creativity can empower other marginalized voices to reimagine a theology that is accepting of all people.

As time goes on, I look to the younger generations of Asian Americans for a hint of what the future might look like for us. I see that personal experiences with ethnic identity are more embraced, more unfettered and, if anything, less focal.

I see many young Asian American academics, artists, writers, entrepreneurs and athletes at the forefront of their respective fields, and I wonder whether they have escaped the trivialization of Asian Americans -- if they must escape at all -- and if they have, whether they have done so by evasion, denial, combat or assimilation.

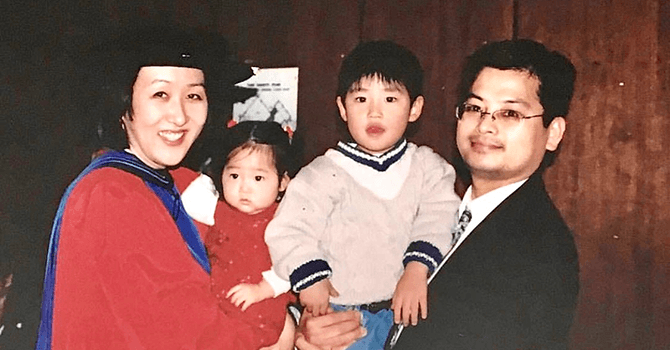

I wonder whether Asian Americans in my children’s generation feel the same conflicted loyalty and resistance toward each other that my generation did. I wonder whether they feel comfortable in a room with other Asian Americans, or whether their inner racial angst emerges like it did for me in 1995.

I wonder what it might be like if I were to enter that Ph.D. classroom today, whether I would feel the same unease at being pointed out by another Asian American, or whether I might instead find some kind of affectionate coalition.

Perhaps what I really hope is that I wouldn’t be abruptly pointed out at all, that I might simply be seen in the room and asked to go out for lunch after.