Editor's note: In April 2024, Greg Moore was suspended from all clergy responsibilities at Edenton Street UMC, where he served as senior pastor for three years, under complaint for charges of sexual misconduct. These charges do not involve children or youth. Moore will not return to his appointment at Edenton Street UMC when the suspension ends.

I never wanted to be a field preacher.

Growing up in rural South Carolina, I developed a healthy suspicion of people who preach outside. There is a long history in the Lowcountry of outdoor pulpits being occupied by traveling evangelists who go from town to town selling salvation to people who have been saved annually at the same tent revivals for as long as anyone can remember.

As good mainstream churchgoers, my parents taught me to properly roll my eyes as we drove by the circus tents surrounded by yard signs that read “Jesus Saves” and “Heaven or Hell?” To this day, the notion of field preaching seems to me more like a spectacle than a sacrament.

The irony is that I happen to be Methodist. Which means that, ecclesially speaking, I am the great-great-great-grandchild of field preachers. One of the predominant stained-glass windows that illumined the sacred story to me as a child was a scene of John Wesley preaching outside to the coal miners.

It was as if the people who designed that sanctuary wanted to remind those of us settled into our pews not to get too comfortable in that building. Our real place, the Wesleyan sunlit shards of glass told us, was outside.

So my faith was born in an unhappy marriage of disdain and gratitude for field preaching. While my family and I liked to distance ourselves from the traveling gospel circus tents, there was also a realization that we found our way to the table because John Wesley, and hundreds like him, became “more vile” for the sake of the gospel and preached outside.

I thought that I had escaped this awkward family heritage until Christmas Eve 2009, when I became a field preacher.

Bishop Al Gwinn had sent me to pioneer the founding of a church in a newly developed area of Raleigh, North Carolina. We worshipped on Sundays in the local elementary school and used people’s homes for discipleship groups and mission planning.

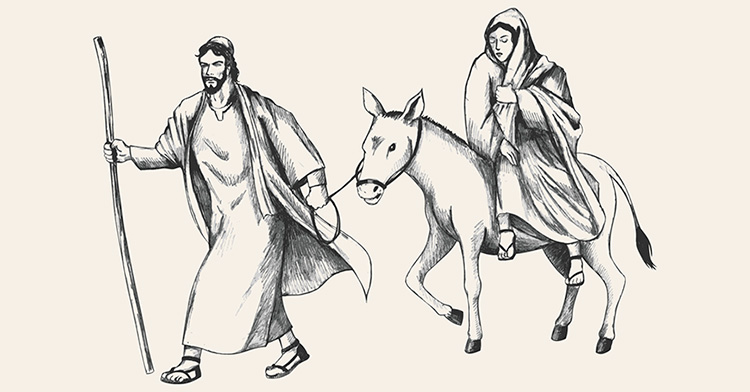

As Christmas was approaching that year, I was outwardly bemoaning the fact that we wouldn’t be able to worship together on Christmas Eve (while inwardly anticipating spending the time at home with my family). Just as I had mentally nestled all snug in my bed, one of our members said, “What if we worshipped outside? That’s where the holy family was.”

I quickly tried to squelch the conversation as visions of circus tents and yard signs danced in my head. But the more they talked, the more the vision grew. Another member said that he knew a man who owned a local farm. He would ask whether we could use his barn.

As it turned out, the “farm” was a donkey and the “barn” was a doghouse where the donkey slept. Nevertheless, we set up the communion table just on the other side of the fence from the “manger,” lit candles and read the second chapter of Luke. And I preached my first field sermon to a crowd of about 20 folks and one very confused donkey.

Six years later, our Christmas Eve service has grown into an event. Some may even say it is a spectacle. We have moved into a bigger barn, which is generously provided by one of the last family farms in Raleigh. News cameras make an annual appearance, and floodlights illuminate a field where thousands of people park their cars as they make their way into the barn. I preach from a trough while cows eat their Christmas Eve dinner around my feet, and we celebrate communion on an altar made from bales of hay.

We even have yard signs.

While part of me instinctively wants to roll my eyes at the whole thing, there is another part of me -- a larger part of me -- that is deeply grateful for the way in which God has, by grace, lured me into joining the holy family outside on Christmas Eve.

And while I’m sure that some people come to worship in the barn on Christmas Eve because of the novelty and spectacle of it all, I’ve also come to be deeply grateful that God, by grace, has lured them into joining the feast as well.

If nothing else, the incarnation reveals to us a God who isn’t above becoming a spectacle for our salvation. There is no other way to describe what happens when God takes on flesh. Royal robes are sullied in kneeling at the trough, and beggars’ rags are esteemed in swaddling Emmanuel.

One percenters are discomfited fearful. Minimum-wage workers find hope. An unwed teenage mother is entrusted with nursing the salvation of the world. And the company of heavenly hosts sings as the fields become sanctuaries in the spectacle of God’s sacrament taking on flesh in the world.

No wonder this draws a crowd. This is worth coming outside to see.

I have come to believe that the body of Christ is quite at home on the feast of the Nativity outside in a borrowed space.

On Christmas Eve, the church celebrates that God, in Christ, has become more vile, the incorruptible taking on the corruptible, the immortal taking on mortality, all for our sake. And following the body of Christ, many of us who are normally more at home in a sanctuary than a stall are able to wonder at God’s sacred descent and to witness to the truth of Mary’s song, “God has lifted up the lowly.”

As much as I would like to think myself and my church above field preaching, the truth is that for at least one night a year, the Christ child invites us outside and lifts us to up to the level of angels. In the barn, heaven and earth kiss as saints and sinners, angels and archangels, and at least one reluctant field preacher sing together over the fields and floods, “Joy to the world, the Lord is come.”