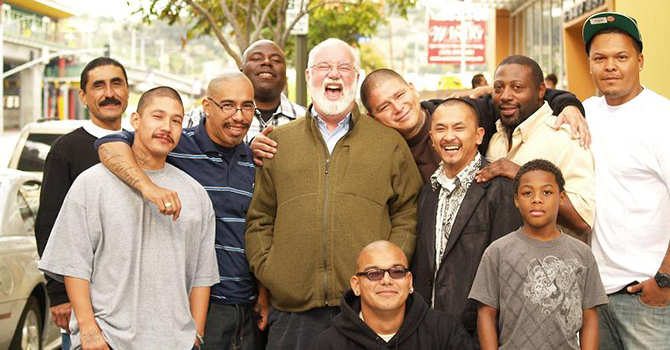

When you think about gang members, if you think of them at all, words like “blessing,” “gift,” “miracle,” “tenderness” and “belonging” are probably not the first ones that come to mind. But they lie at the heart of Homeboy Industries’ work with and ministry to former gang members in Los Angeles, says Father Gregory Boyle, a Jesuit priest and Homeboy’s founder and executive director.

With roots dating back to 1988, Homeboy Industries is the world’s largest gang intervention, rehabilitation and re-entry program. In addition to providing a variety of support services, the organization operates several social enterprise businesses including a bakery, a grocery store and two cafes, where former gang members are paid to learn job skills.

Boyle readily admits that he doesn’t concern himself too much with the practical details of running a large organization with an annual budget of nearly $15 million. He leaves that to others to handle. Instead, he focuses on the work of transforming the lives of former gang members and ex-convicts.

“Discover the gift of who each person is, and then invite people to live in each other’s hearts,” he said of Homeboy’s work and ministry. “And then hope that people will not only discover their gift and their own goodness but that they’ll live out of that place with each other, because as human beings, we’re just astoundingly hard on each other.”

Boyle describes the Homeboy staff as “reverse cherry pickers” who deliberately choose to work with “the belligerent and the difficult,” people in great pain who have “been through the wringer,” to provide them with job opportunities and support services.

The result? Human connection, even tenderness and belonging, he said.

“Tenderness is sort of contagious,” he said. “And at our place, you feel it the minute you walk in. It’s baked into the walls, and it’s very compelling. Homies will walk in and go, ‘I want to work here.’

“‘I need a belonging place’ is what a homie said to me once. It’s a belonging place, where nobody is outside of that sense of belonging.”

Boyle is the author of “Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion,” a collection of parables about his life working with gang members in Los Angeles.

Boyle was at Duke University recently as a practitioner-in-residence at the Kenan Institute for Ethics. While at Duke, he spoke with Faith & Leadership in an interview conducted by L. Gregory Jones, the senior strategist at Leadership Education at Duke Divinity and a professor of theology at Duke Divinity School.

Listen to their complete conversation or read the edited transcript below.

Q: In “Tattoos on the Heart,” you say that your life wouldn’t make sense apart from God. Yet you’re a social entrepreneur and innovator doing this incredible program at Homeboy Industries. What does it mean to root your vision in the story of God and in relationship with God even as you think about the larger horizon of your work?

Well, I agree with Ignatius, who talks about the God who is “always greater.” You’re always trying to inch yourself closer to the more spacious, the more inclusive, the more oceanic sense of who God is. It’s a formulation that’s always being calibrated.

You go, “Does God want anything from me?”

And then you go, “No, I think God only wants for me” -- and suddenly, you get to another place.

If my notion of God when I was 5 or when I was in the fifth grade is different from now, when I’m 61, then why wouldn’t my notion of God change 20 minutes from now or the day after tomorrow?

It does if you’re open and if you don’t allow your sense of who God is to atrophy and to become tiny, where you’ve created God in your own image -- when, as Anne Lamott says, you discover that God hates all the same people you do. We can’t help but create God in our own image, but we can sure catch ourselves.

And that’s important. Like right now, I’m getting text messages from thoroughly discouraged gang members in Los Angeles whose hair is on fire over intractable problems. And they go, “Why would God send this my way?”

These are easy ones, you know. God didn’t, and life is hard, and I believe God protects me from nothing but sustains me in everything.

The mystery, or the secret, of the ministry of Jesus is that God was at the center. So you want the same thing to be true [for you], but you’re always trying to refine what that means, and that always involves how you deal with people.

If ours is a God who is too busy loving us to be disappointed in us, then imagine what that means for your ministry or being. And imagine, if ours was a God who didn’t want anything from us but only wanted for us, then suddenly, all these walls and doors are opened.

Q: Many stories you tell are about how you see other people in light of God and how that leads you to stand in awe and to notions of blessing and a sense of hope. You even describe much of the work of Homeboy Industries as about “miracle” rather than evidence-based outcomes. How do you reconcile all that -- awe, blessing, hope and miracle -- given the very practical work you’re doing with people at Homeboy Industries every day?

Well, I try not to think about it. I let other people think about that part, the part about evidence-based data. It feels sort of antithetical to who we are, yet there’s a part of my brain that says, “We’ll get funding from this organization if we do this.”

I understand that; I’m not stupid. But I still feel that we’re called to be faithful and not successful. Somehow, you land on an approach that you say, “This is good and true and right and just,” and then you don’t care what the outcome is. You’re just doing what you can, and what you’re doing is true and right and just to the best of your ability.

Once you’re doing that, then outcomes are really not my concern. It’s freeing to have that happen. Unless you get to that point where you don’t care about outcomes, then you start to shift, and you only work with the poor who are most likely to give you good outcomes, and that’s a danger.

I’ve seen it happen a million times in educational institutions, including Jesuit institutions. An institution might say, “We’re going to teach the kids that no one else will touch, that no one else will teach,” and then you do, and you’re bruised and battered after your first year. Then a board forms, and they go, “How many of these kids have gone on to college?” And we look around and say, “Well, there was one.”

And the board goes, “Oh, only one. Well, that’s interesting.”

Five years later, every one of your graduates is going to college. But it isn’t because you’ve mastered how to teach these kids. It’s because you stopped teaching the kids that you set out to teach and you slowly got to the place where you are standing with the most likely to succeed rather than the least likely to succeed.

At Homeboy, we’re reverse cherry pickers. We only want to work with the belligerent and the difficult, because we know that their belligerence has to do with their pain. We think that our environment is particularly suited for folks who have been through the wringer.

Q: Talk some about how you invite former enemies to work alongside each other and into new relationship.

I always invite on plane trips enemies who don’t speak to each other. They may work with each other, but they don’t speak to each other, at least initially. So you throw them together in a hotel room just to mess with them.

I’ve had this happen many times, where you have these homies -- enemies -- in the car, and you’re driving to the airport, and they won’t speak to each other. But then, once they share the experience of being on a plane for the first time, there’s no way human beings can sustain the silence in the face of that. They’re in the midst of a shared and new experience, and that’s kind of miraculous.

I remember I had two guys, Johnny and Danny, from enemy neighborhoods. We flew to San Francisco and went out to dinner, and little by little, stuff was breaking down. Then we went on the boat to Alcatraz, which is the obligatory stop they all want to go to, and they were thrilled.

They go up to the front of the boat -- they’re huge guys with tattoos, so everybody’s leaving that part of the boat -- and Danny gets to the very front of the boat, and he stretches out his arms like the scene from “Titanic,” and he yells, “I’m the king of the world!” And more people move away.

We’re standing there, and he’s at the very tip of the boat, and a tugboat goes by. And Danny cups his hands and shouts, “Ahoy, mates!”

And Johnny goes, “What’s that?”

“Boat talk,” he says. Like, “You wouldn’t understand.”

It was just so joyous. We were howling with laughter. In no time, you had gone from 0 to 60, from absolute disdain to “We are in this together,” because we’re having shared experiences.

So it’s not just shared ventures or tasks, like working together in the bakery, though it is that, too. Richard Rohr says that women work things out face-to-face but men work things out shoulder-to-shoulder, and that’s absolutely true in my experience with the men enemies at Homeboy. Somehow, something is getting worked out. There’s some kind of sense where they go, “This person is more the same as I am than different.”

I remember two enemies who were so much the same they even looked like each other. I walked into the bakery, and one guy put his arm around his enemy, and he says, “Don’t you think he looks like an ugly version of me?”

Three months ago, they wouldn’t even acknowledge that they shared the same oxygen in the same room. But now they’re getting to a place of connection, even if words didn’t get them there, which is kind of a key.

Q: How do you see blessing as part of your ongoing work, amid so much pain? How do you see it in relation to the overall ministry of Homeboy?

Well, in a concrete, specific way, homies are always asking me for blessings, especially on Fridays -- because the weekend’s coming, and there’s a little bit of magical thinking there.

They never say, “Father, may I have your blessing?” They always say, “Hey, G, give me a bless, yeah?”

They stop me wherever, and it’s very touching. And sometimes I’ll say, “Now you give me a blessing.”

They’re very sweet, very wonderful. They’ll say, “I don’t know how to do one.” But they always do. They know how to do one exceedingly well.

It’s about gift. Discover the gift of who each person is, and then invite people to live in each other’s hearts. And then hope that people will not only discover their gift and their own goodness but that they’ll live out of that place with each other, because as human beings, we’re just astoundingly hard on each other.

Tenderness is sort of contagious. And at our place, you feel it the minute you walk in. It’s baked into the walls, and it’s very compelling. Homies will walk in and go, “I want to work here.”

“I need a belonging place” is what a homie said to me once. It’s a belonging place, where nobody is outside of that sense of belonging.

Not long ago, Pope Francis said an odd thing: “Jesus wants to include.” It’s an interesting way to phrase it. He could’ve said, “Jesus used to include” or, “Inclusion was important to Jesus” or, “You should include.”

It’s an odd phraseology -- “Jesus wants to include” -- which is to say now and here. It’s what he wants to do now. He’s not talking about you; he’s talking about Jesus. It’s the same kind of paradoxical moment as in, “I was in jail and you visited me; I was hungry and you fed me.” It’s the same kind of total identification, where Jesus wants to include today, now. And then you just feel like, “Wow, I’d like to join him.”

Suddenly, you’re dismantling the barriers that exclude, and you’re participating in the birth of a new inclusion, and that’s huge. That’s something worth giving your life to, especially when we’re so inclined to scapegoat and to compete and disparage and strike the high moral distance between “us” and “them.”

Jesus wants to include. Who am I not to?

Q: Can you talk some about the tension in Jesus’ wanting to include when you’re navigating the struggles of somebody who’s not yet ready to come clean about their drug use, for example, or other challenges. How do you include and deal with those challenges and also have accountability without becoming judgmental and excluding?

It’s tough, and I’ve learned a lot from the homies in this regard. That’s why success and failure are meaningless concepts.

If somebody’s here with us, we drug test when they get in, and then randomly and constantly. So when you test somebody after three months and there’s crystal meth in their system, usually we say, “Hey, let’s go to rehab, and then when you come back, you can start exactly where you left off.”

Often enough, they’ll say, “I don’t need drug rehab, thank you very much,” and they leave us.

One homie, Fabian, always says, “Progress is progress; we had them for three months.” And this is a kid I would hire and then I would fire, like so many others there.

But progress is progress, so why would you want somebody to be the whole and complete version of anything? He made a lot of progress in three months; hopefully, he’ll come back. You can never take that progress away from him. It was three months of being held tenderly in a community that held him in high regard.

Who knows why he relapsed or got high? I suspect it’s because once you start to do the work, it’s too painful to look at it, and you want to self-medicate. But we’ll pick up where we left off and hope it’s soon.

But it’s never helpful to say we failed this guy. No, you meet halfway. You hope for the best. Sometimes it works, and sometimes it doesn’t.

Q: You’ve said that part of what attracted you to the Jesuits was a sense of hilarity and laughter. Tell us about the culture of humor in your ministry and in Homeboy.

I think it’s about joy. It’s like in your marriage vows, for example. It’s not that in good times we’re going to be joyful and in bad times we’re going to be sad. No, it’s joy all the time, and that’s the key. It’s about choosing to be joyful in good times and in bad, in sickness and in health. That’s a decision. Otherwise, you wait for the joyful thing to come in order to be joyful, as opposed to maintaining joy all the time.

It turns out that joy comes with a maintenance contract. How do you maintain a joyful heart? Part of that is to stay anchored in the present moment -- but to find the sacred, not to confine the divine. Ignatius always talks about finding God in all things.

There’s a homie named Grumpy, a huge guy, and whenever he tells these big, long stories, when he gets to the end, he wants to say, “And lo and behold …” But he never says this. He always says, “And holy befold …” I never correct him, because it’s way better than the original, you know?

“And holy befold …”

Like the holy is unfolding, revealing itself in every moment, not in some once-every-10-years peak experience. Every single moment is that moment where, “holy befold,” something extraordinary is happening, soaked with joy. That’s a key. It’s a decision.

So at Homeboy, joy is a decision. You look around all the time. There’s a guy named Joshua, covered in tattoos, and he’s called upon one day to be my runner. The runner stands right in front of my door with the list of who’s the next to come in. His job is to come in and tell me the name of the next person. I mainly have a lineup of homies to see me, but occasionally I’ll have an appointment with an attorney, a donor or a kid with a university essay they have to write. So I signal him with my fingers to send the next person.

He comes in, stands in the doorway and says, “Your 3 o’clock appointment is here to see you.” I say, “Thank you, send him in.” Then he turns to a homie, and he goes, “I always wanted to say that.” But he sounded like the damn butler from “Downton Abbey”: “Your 3 o’clock appointment is here to see you, my lordship.”

It was so delightful.

“I always wanted to say that.” Where the heck does that come from? I have no idea.

But God’s nickname for us in the Old Testament is “God’s delight.” That’s a good thing to decide to be -- to be the duty to delight, to be on the lookout for it, because, “holy befold,” it’s happening all the time.

Q: That’s wonderful. Paul writes to the Philippians, “Rejoice in the Lord always” -- while he’s in prison. It’s not as though he’s having a great day, saying rejoice when the mood strikes you or when you get great news; it’s in the midst of prison you can still rejoice always.

Yeah, rejoice always. Rejoicing is what we’re meant to do. Jeremiah says the same thing. He says, “Be not crushed,” because rejoicing is the order of the day. It’s the same concept of when anybody else would choose to be crushed because circumstances seem to require it. It’s kind of “agere contra,” the Ignatian principle of going against where you think being crushed is in order, to choose something else, choose rejoicing. It’s what we’re meant to do.

Once you tap into that, then everything is pretty hilarious. People are very funny and smart and tender.

Q: I’m struck, thinking about the ministry of Homeboy and that sense of joy, delight, kinship, that you’re dealing with a population that struggles and has lots of brokenness and pain. You’re inviting them into a new culture that learns to have awe for each other and to embrace each other. What are the practices that you’ve cultivated at Homeboy to help people catch hold of this culture of kinship and love?

Well, one is therapy. We don’t demand it of anybody, but we’re constantly reminding people that we think this’ll help. We don’t force anybody, because if you force somebody into therapy, then you’re just wasting an hour of therapy. But you hope for it, and once they do it, their dragons come out of the cave, and then they spend a lot of time trying to get the dragon back in the cave.

What Homeboy hopes to do is to invite them to take dragon-riding lessons. “It’s out of the cave; don’t try to get it back in. Let’s ride it, you and me; let’s do it together.”

So you ride this thing, where terrible things happened to him when he was a kid. I had a kid the other day say, “I would not wish my childhood on my worst enemy.” And when you hear the specifics, you go, “Yeah, that’s right; I wouldn’t wish that on anybody.” Just horror stories. And how full of judgement we can all be about that kind of stuff, where we blame the victim, where we scapegoat somebody.

They were all things I’ve never had to carry, and I grew up in Los Angeles, the gang capital of the world. But I never had to contend with dragons and caves. That’s sheer dumb luck, just the serendipitous random lottery of ZIP codes, that I happened to be born on the west side instead of the east side. So how dare me strike a high moral distance between my experience and their experience or suggest, “Oh, I never joined a gang,” as if you could even make that comparison.

Not all choices are created equal. That’s one of the things that homies come to see, that they never chose this gang lifestyle. It chose them by virtue of where they were born and who their parents were and what they were exposed to. That’s an important discovery.

Gangs are, in the end, places kids go when they’ve encountered their life as a misery, and misery loves company. You can at least come to terms with that, and then you’re at a place where you’re ready to be liberated to the next place.

Q: What about sustainability? You went through a rough time in 2010, where you had to lay people off, and now you’ve got some revenue-producing enterprises that are generating 30 to 40 percent of your budget. What have you learned over the years about raising money, about the kinds of ways to sustain the vision?

Mainly not trying to think about those kinds of issues, just because it’s the only thing that keeps me awake at night. Probably less so now, because I have other people worrying about it ahead of me.

It’s exasperating. I always think of the crumbling Hollywood sign, which is an icon in Los Angeles. All you had to do was mention in the Los Angeles Times that it was crumbling, and people were falling over themselves. They raised $6 million in a day. If we were the crumbling Hollywood sign, we’d probably be in good shape. If we were a shelter for abandoned puppies, oh my God, we’d be endowed by now.

That’s just a way of saying, “Yikes! Why would we not afford a second chance to somebody?” Sister Helen Prejean says often enough, everybody’s a whole lot more than the worst things they’ve ever done. The more we can remind ourselves of that, the better.

Q: You are a brilliant storyteller. How do you think about the craft of storytelling and locating that within the larger story of God?

I’m not really sure about process. But I’ll tell you a story. It’s a recent one.

There was a kid I knew all his life, since he was 13 -- Danny. He was a knucklehead, and was allergic to walking through my doors. He just wasn’t going to do it. I knew him on the streets and in the juvenile hall and in probation camp. Then he went to prison, and got out at 20, just a year ago, to discover that his mom had had cancer and had six months to live.

So he spent time with her daily, kind of her hospice caregiver, never left her side. I saw him there; it was very tender. Then she died. A week later, I buried her, and a week after that, he walks into my office for the first time. So he’s in our 18-month program.

He’d only been with us four months, and I watched him working with enemies. He was into his neighborhood and into having enemies. In recovery, they say it takes what it takes -- the birth of a son or the death of a friend, taking care of a mother who’s dying of cancer. Who knows what it takes? But I watched him come alive.

So he comes into my office, and he says, “What happened to me yesterday on the way home has never happened to me in my life.”

He was on the Gold Line, the train from Pasadena to the east side. He’s in the car, it’s packed, but he’s able to get a seat. Right in front of him, hanging onto the pole, is a guy who’s a little bit drunk. Danny can tell he’s a homie because of his tattoos, but he’s an older guy. He doesn’t know him.

Danny’s wearing a sweatshirt that says “Homeboy Industries -- Jobs Not Jails” across his chest. And the guy says, “You work there?”

And Danny says, “Yeah.”

And the guy says, “Is it any good?”

Danny says, “Well, it’s helped me. In fact, I don’t think I’m going to go back to prison because of this place.”

Then Danny stands and he reaches in his pocket and he finds a piece of paper and a pen, and he writes the address of Homeboy Industries and hands it to the guy.

The guy studies it. And Danny says, “Come see us. We’ll help you.”

And the guy says, “Thank you,” and he gets off at the next stop. Danny sits down, and now he starts to get a bit filled with emotion, you know?

He says to me, “What happened next has never happened to me in my life. Everyone on the train was looking at me. Everyone on the train was nodding at me. Everyone on the train was smiling at me.”

Then he could barely speak. He says, “For the first time in my life, I felt admired.”

And he cried. And I cried. It’s like any biblical story where somebody is experiencing sight after not having it, or liberty from whatever place they felt captive. And I didn’t do that to that kid, but boy do I feel grateful to witness that it happened.