About 15 years ago, a group of seminary professors and I took the mail boat out to Little Cranberry, one of the many small islands that dot Maine’s rocky coastline. We docked at tiny Islesford and walked through the woods to a cottage nestled among the pine trees in the quaint harbor town.

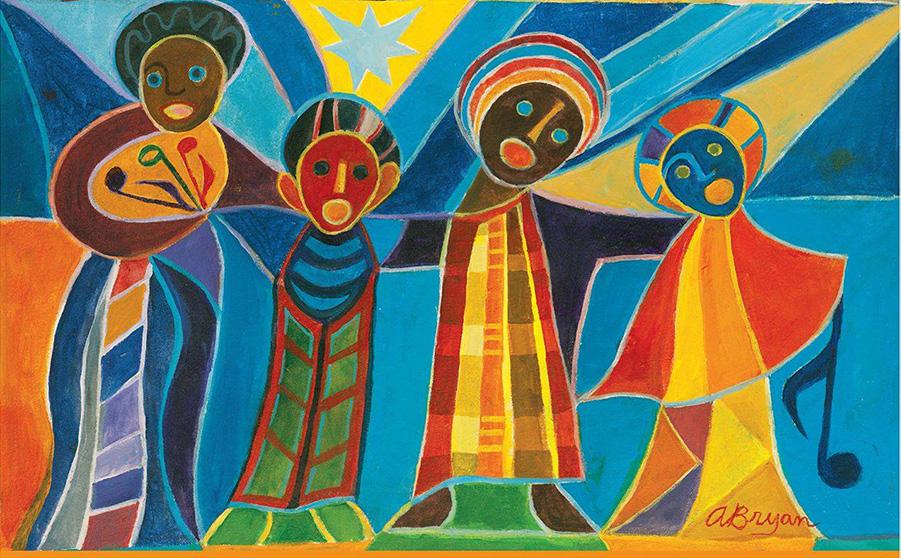

We were visiting the home and studio of Ashley Bryan, a now-97-year-old African American storyteller, artist and illustrator. After an award-winning career studying, teaching and creating art around the world, Bryan moved to the island to continue his craft in retirement.

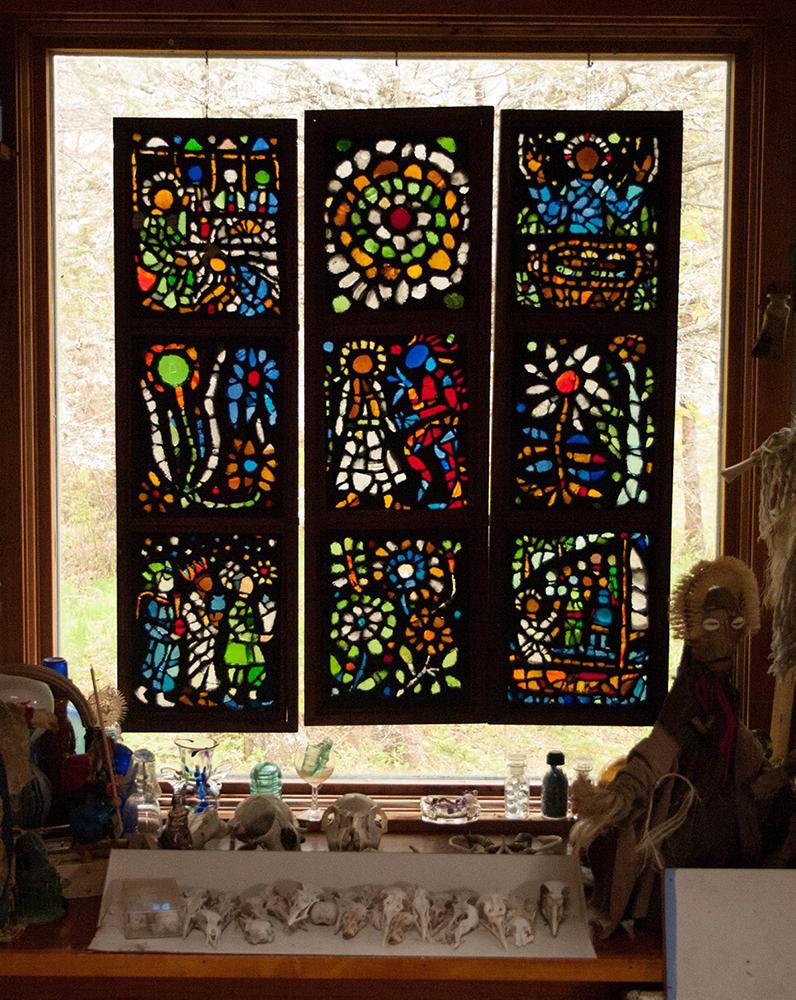

His living and working space, which now includes an adjacent showcase pavilion as part of the Ashley Bryan Center, is a rich testament to his work. Every surface, nook and cranny is crammed with his collections, collages, paintings, sculpted figures, sea glass, driftwood and shells. He sees beauty in whatever he finds washed up on the ocean shore.

The windows are aglow with brilliant stained-glass-like panels, made from gathered sea glass, that depict the life of Jesus.

Perched throughout the space are the hand-held puppets for which he is famous. Created from his findings and papier-mache, they add to the fantastical atmosphere. The place is a hub for both children and adults, who flock from the island, the mainland and around the world to see his work.

For his themes, Bryan draws on African folk tales, proverbs and spirituals (his parents descended from West African slaves from Antigua). His art can best be described as collage, the art of creating something new -- new meaning and new beauty -- out of the scraps and broken pieces that the world sees as disposable.

Bryan has the humility to see value in the broken pieces, the vision to see what they could become, and the wisdom to curate and place them alongside one another in meaningful and beautiful ways.

His work of collage is holy work than can teach us how to curate and assemble our broken pieces into something new, especially in this time of COVID-19.

Jan Richardson, another artist and student of collage, came to appreciate the creative process as a way of drawing closer to God, a kind of spiritual practice. “I found that something transforming happened for me in the process of cutting and tearing and pasting and piecing together to create something new,” she said in a 2014 interview.

It was a practice, a way of prayer, and a metaphor for her life, she said. “I would sit at the drafting table and cut and tear and paste and piece together, and [I realized that] taking the light and the dark and the rough and the smooth and the pieces that I might prefer and the ones that might otherwise get thrown away and using all of those to create something new, that God was doing much the same work, and continues to do much the same work, in my own life.”

In that way, she said, God is “the consummate recycler,” using all of our pieces, wasting nothing, in creating something new. For Richardson, the call not just of the artist but of the Christian and every person of faith is “to wait with the pieces, to open our eyes to the pieces” and then “to allow ourselves to begin to imagine, and to allow God to imagine through us, what could these pieces become.”

What might these words mean in this time of COVID-19? Many of us now “wait with the pieces” of our lives, wondering “what could these pieces become.” We are holding the pieces and slowly -- or, in some moments, rapidly, at the speed of water from a firehose -- imagining new ways to connect them.

Can we create something of meaning and beauty? How is God imagining through us new ways of being with each other, both now and in whatever “next” will occur? How will God “open our eyes” to a new, life-giving curation of our pieces? What does God celebrate in our pieces that we need to learn to see?

This kind of vision is what my husband, Norman Wirzba, calls “iconic seeing,” as modeled for us throughout the Gospels by Jesus. Exploring this idea in his book “From Nature to Creation,” he writes: “Over and over again we see that Jesus never simply sees others as the surface beings that they are. He sees beyond the surface and into the creative, enlivening love at work within them. … His seeing and response -- the compassionate response being the clearest indication that iconic seeing has occurred -- is a joining with the divine love always already at work within creatures.”

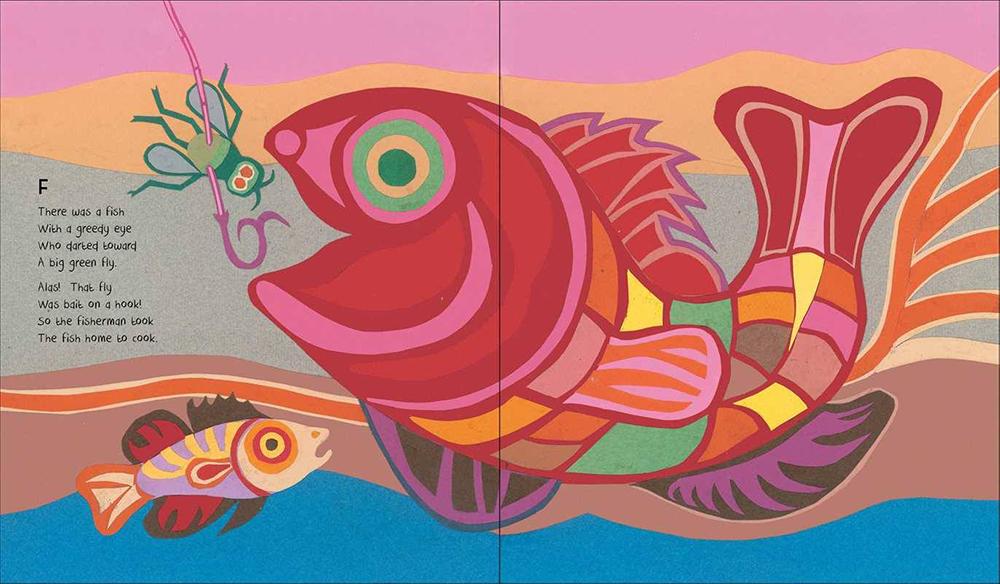

Iconic seeing takes practice. For $3.50, a local reuse arts shop sells bulging bags of scraps labeled “Collage.” It is an adventure to open one and let the contents spill across the kitchen table. Out pour the castoff pieces of many lives: stray playing cards, CD jackets, lengths of rickrack, Disney stickers, old birthday cards, postcards of Greece, bits of wrapping paper and ribbon, maps of Colonial Williamsburg, cracked photos of someone’s cousin’s graduation -- all waiting to be curated and assembled to create new meaning.

In my experience, some collage makers see and use the pieces for what they are -- a photo of a dog, for instance. Others see the dog but also look beyond the surface representation to the color, pattern and texture of the image and snip away accordingly.

One of these bags plus a glue stick would make a great graduation gift for a seminary student. As Bryan has said, “You must practice daily with whatever you want to grow in or grow with.”

It takes practice to see the beauty in the pieces and in people, especially in our currently fragmented lives. Are there pieces that are continually neglected? Are there pieces that can never be used?

How do we learn to imagine something meaningful and beautiful from the current bits of our lives, neighborhoods, churches, institutions and larger world? The work here is not only in the valuing and the visioning but in the curation and the assembly. It is good and holy work.