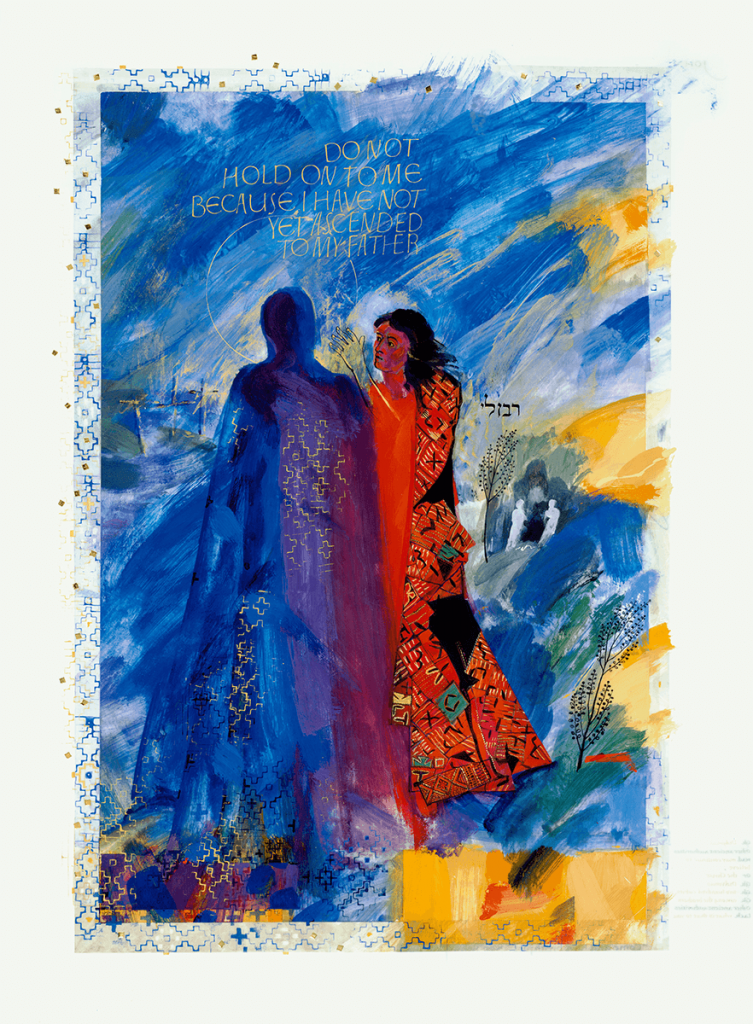

This Easter, I am pondering a copy of a painting that’s been taped to my door throughout Lent -- artist Donald Jackson’s illumination “The Resurrection” from The Saint John’s Bible. The image is helping me delve more deeply into the familiar story of John 20 and see it in new and life-giving ways.

I regularly use the prayer practice of visio divina, or “divine seeing,” both in my own prayer life and with groups. Like lectio divina, visio divina involves multiple readings of a biblical story or text but then adds the step of studying an illustration that further illuminates the Scripture passage in some way.

Not only does visio divina invite us to meditate on what we are seeing; it invites us to be surprised and transformed as we encounter God through the illuminating image.

More than a kind of visual exegesis, it is a way of letting an image speak to us the way a good story does, teaching us something about the text we might not otherwise discover. The Saint John’s Bible is a rich source of images to use for this practice.

You don’t need to be an artist or an art critic to practice divine seeing. I use three simple steps: see, think and wonder. I ask myself: What do I see in the illustration? What does it make me think about? What does it make me wonder?

So what do I see in Jackson’s “The Resurrection”?

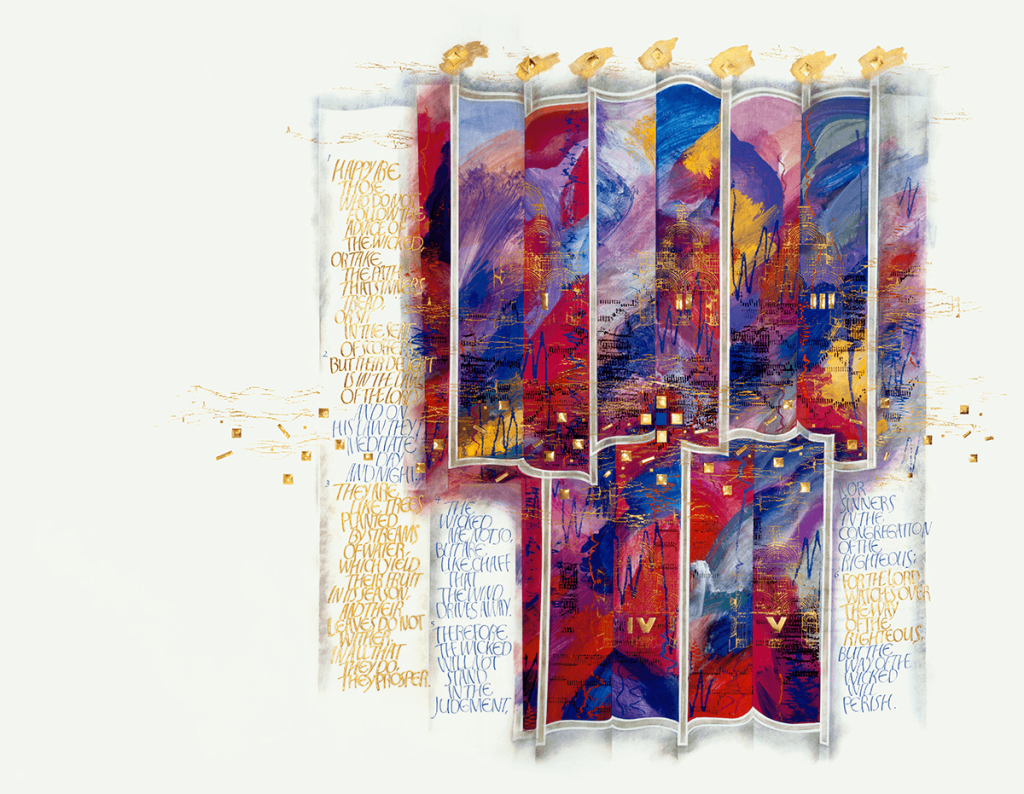

It’s helpful to linger in this first step, simply seeing without trying to analyze anything. The first thing I notice is that I’m seeing only the shadowy back of the risen Jesus, not his face. The blues of his cloak blend with the blues of the background, making it hard to tell where the human form starts and ends.

I see Mary Magdalene lit up by the intense, fiery red in her cloak, dress and face; yet her hand, which reaches out to touch Jesus in an intimate act, is almost translucent. A piece of her cloak overlaps his, and some of Mary’s red is reflected onto Jesus’ blue. The letters next to her shoulder spell out “Master!” -- her word of recognition, in Aramaic.

I see the three crosses in the background on the left, and to the right of Mary Magdalene, the empty tomb guarded by the two angels. Down the right side of the illumination, I see four blocks of intense golden light. Bits of the light spark in various other parts of the blue paint, particularly around the three crosses and in the pattern on Jesus’ cloak.

Arising from the ground are two stalks of wheat, one by the tomb and one at Mary’s feet. I notice that the lacy pattern on Jesus’ cloak also runs around the border of the illumination, broken up in places by the blocks of gold. At the top of the image, also in gold, the words “Do not hold on to me because I have not yet ascended to my Father” overlap Jesus’ halo.

What does the illumination make me think about?

The image makes me think about how we see Jesus’ glory in one another -- in this case, as revealed through Mary’s perspective. I think about Jesus’ resurrection power, reflected not in his face or on his body, which are hidden, but only on Mary’s face and body, which are lit up and almost on fire with his love. I also think about the blocks of golden light that seem to be coming from the front of Jesus, hurled into the blue world by his power. I think about the awe on Mary’s face as she receives the gift of fully beholding the risen Christ.

I think about how the play of golden light and blue shadow creates movement throughout the illumination, echoed in the words of Scripture at the top. Mary cannot hold on to Christ because he has not yet ascended. Her hand must stop in midair as she reaches for him. It is a powerful time for Mary to see him, in that shadowy, not-yet-ascended phase of Jesus’ transformation. Jonathan Homrighausen, in his book “Illuminating Justice,” writes: “Like Mary Magdalene, we too must let go of Jesus’ physical form, as we cannot see his face in this illumination.”

I think about how Jesus’ risen glory is first reflected in a woman. Mary’s red figure is at the center of the piece; her strong, feminine presence dominates the illumination, and literally frames it, through the lacy motif that borders the picture and lights up Jesus’ cloak as well. Mary’s own cloak is a boldly patterned textile print that stands out amid all the blue.

I think about how the two stalks of wheat are perhaps spun off of or out of the risen Christ to become the “bread of Christ” when he is fully ascended.

Scholar Jeffrey Bilbro thinks of this illumination as depicting “an external yet personal call, and a faithful, subjective response.” He writes: “Mary models for us what happens when we come face-to-face with the Word of God. And in an analogous way, when we read the written words of Scripture, we are likewise read, interpreted, transformed, and found out. We are not the illuminating subject but the illuminated object, receiving our subjectivity as a gift.”

What does the illumination make me wonder?

I am struck that not only is Mary the first to see the risen Christ, but she enables us to see the resurrection through her eyes -- the eyes of a woman who is powerless and, to some, a prostitute.

From the powerless in that society, we see an intimate and powerful scene of resurrection love. Finding that love in others is our only recourse, our only clue to the beauty of Christ’s embodied love. His shadowy back points us to the world and to one another, especially the marginalized. “Don’t look at me,” he seems to suggest. “Look at them!”

In our world, and especially in our nation, this image is a call to where I might see the love of the risen Christ this Easter. I wonder whose face I must study. The face of a baby? Of someone with dementia? Of a homeless person? An undocumented worker? Someone who will vote differently from me? Someone wearing an N95 face mask?

I wonder who in your world is reflecting the risen Christ? Where have you seen Jesus’ love radiating lately? Where is that radiating unexpected, and where has it shown up as a fiery red beacon at the center of your life’s picture?