What does it mean to have a “good death”?

After bearing witness to 200 deaths in one year as a hospital chaplain and grieving the death of her own mother, the Rev. J. Dana Trent decided to draw on her experience to answer this question and write a guidebook about planning for death.

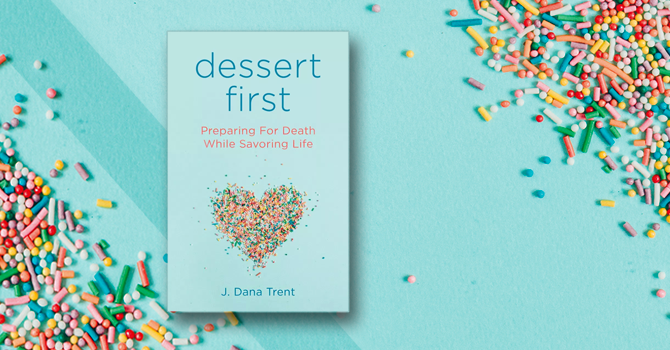

The book, called “Dessert First,” encourages readers to prepare for death while savoring life -- to begin with the end in mind.

“When you prepare for death, it makes life sweeter,” Trent said. “You can truly savor it, because you’ve thought about the end already and you’ve talked about it with your family and friends.”

Trent is a graduate of Duke Divinity School, an instructor of world religions at Wake Technical Community College and the author of several books, including “One Breath at a Time” and “Saffron Cross.”

Trent is a graduate of Duke Divinity School, an instructor of world religions at Wake Technical Community College and the author of several books, including “One Breath at a Time” and “Saffron Cross.”

Faith & Leadership assistant editor Katie Rosso talked with Trent about grief, her time as a "death chaplain," and beginning the conversation about dying. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: In writing this book, what was the role of your own grief? Did you choose mindfully to make it an in-motion grief process?

J. Dana Trent: The year after I graduated from Duke, I was a chaplain at UNC for their yearlong residency. 2006 to ’07 was my chaplain year, and in that year I became known as the “death chaplain.” My specialization became sitting with people, being present with patients and families during this very sacred transition. I earned that moniker because the unit that I worked on had the highest number of deaths in the hospital. But it wasn’t because they didn’t do their jobs; it was because they were really good at their jobs. They were literally the last step. If the medical ICU couldn’t fix you or send you home, it was the unit that would help you have a peaceful transition.

After that year, I really wanted to write this book. I thought about it and marinated on it, but other projects came about, and so the book just never landed until August two years ago.

I was on a plane, heading home from Nashville to Raleigh. I had just gotten a call that my mother was in ICU and that she was actively dying, and I got an email that a publisher was interested in the book. I had been pitching the book all along as this yearlong chaplaincy experience, and I knew then, reading the email on the plane and knowing that Mom was probably in the last two weeks of her life, I knew that it was the time. It was the time to implement all the lessons I’d learned in chaplaincy and grieving loved ones into giving Mom a good death -- but then also taking it wider and teaching others how they can do that for themselves and their loved ones.

F&L: In the book, you also include practical, legal, spiritual and religious resources. How did you go about compiling those?

JDT: The resources definitely began in chaplaincy, because I saw my first person die in chaplaincy just a few weeks in. I learned quickly that even though 7,400 people die every day [in the U.S.], most of us aren’t prepared. Most of us don’t have advance directives, living wills, estate paperwork -- or even anyone who knows these things who would make a decision for us.

If you and I were to get in a car accident this afternoon, heaven forbid, does anyone know what kind of care we would want? In chaplaincy, I saw that happen over and over and over again. So during that year, we assisted patients and families deal with the paperwork, and I learned quickly that those kinds of practical and legal resources are imperative. They’re often just as important as the religious, sacred, meaning-making rituals that we employ in that transition toward death. You can’t sit with someone and be present with them in death if you’re worried about those legal and practical decisions that have to be made. And it’s really difficult to do both at the same time. The greatest gift you can give yourself and your loved ones is starting the conversation talking about all of this.

F&L: What did you read in preparing for this book?

JDT: Two texts that anchor this book are [memoirs by] Kate Bowler and Joan Didion. Others, like Caitlin Doughty, are woven throughout, but Bowler and Didion were really my anchors. What I love most about them is they are personal narratives on grief and death, and I have never encountered two other writers who so vividly capture how grief feels and what death means to them.

F&L: You frame the introduction around a Kate Bowler quote: “We’re all terminal.” What inspired you about that quote?

JDT: It was actually inspired by lots of conversations I had with my mother in the airport, so “terminal” is a great play on words -- the airport terminal, and then Kate, of course. Kate is right. We are all terminal. Some of us just have more information about when and where.

In her case, she’s got a lot more information about her particular diagnosis and what it means to her and what it means to be chronic, not curable. But for the rest of us, terminal means that none of us are getting out of here alive. The death rate is still 100%, and so the fact that we ignore that and we play and listen to these ridiculous airline safety videos about using your seat cushion as water wings in the event of an emergency, it’s like we’re throwing everything we can at our lives in order to keep ourselves alive. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it’s important to recognize that death is not an “if” question. It’s a “when.”

F&L: You use a variety of theologies in the book, especially in the “Theological Views of the Afterlife” resource. Beyond the story of your chaplaincy, how did your personal faith intersect with the creation of the book?

JDT: A couple of things played into this resource section. When I graduated from Duke in ’06, I could read Greek and Hebrew texts. I had a wonderful, robust theological education. I was very orthodox, small o, in my Christian views. Duke had equipped me well in the classroom, but what I discovered was that in the room with a dying patient, orthodox theology isn’t necessarily important or what someone needs at the time of death. Pastoral care is what they need.

They need reassurances that they will be remembered, reassurances that they have been forgiven, that they are loved. Presence, rituals, meaning making. All of that is really what matters to the dying patient and their family.

If we jump way ahead from my M.Div. to teaching world religions and being married to a devout Hindu, I’ve realized that when I walk into a patient’s room or a family member’s room who is dying, in that liminal space, there are all kinds of theologies and spiritual traditions that have spoken to this person throughout their lives. So it’s important for all of us to be informed about those various theological views so that we can help others have meaningful rituals that will mean something to them at the time of their death.

We’re not necessarily imposing our own views or rituals on them but thinking about what is it that a Muslim patient would want, or what would be useful to my Buddhist friend as I’m sitting with her at her deathbed. Those are the kinds of things that I hoped this resource would assist people in thinking through. The world is so diverse right now, how do we sit with our neighbor both in life and in death?

F&L: In Resource 1, “Conversation Starters,” you refer to yourself as a “crazy lady” who actually plans her own funeral. Tell me a little bit more about that and what, in a nutshell, you’re recommending that people face about death.

JDT: In a nutshell, I’m recommending that they start the conversation even in its most simple form. It could be humorous -- five minutes at the dinner table, a joke from a movie or contemporary culture -- just starting the conversation. Even when the kids balk and say, “I don’t want to hear that. You’re not going to die. There’s no way.”

Your kids will still remember if you joked about “Meet the Parents” and the cat peeing on grandma’s ashes if in that way you say to your children, “I don’t want to be cremated. I want to be buried.” They’ll remember that anecdotally. That will stick in their minds.

But more importantly, I want to be the 38-year-old crazy lady you can blame it on. I want you to say, “I’ve been reading this book, and this lady is nuts, and she’s planned her own funeral.”

And all of that is true. All of my legal paperwork is done. My obituary is written. My service is done. All of it is in black and white. The reason I’ve done that is because I realize that, at 38, I am closer to death than I am to birth. I’ve officially hit midlife for the average American life span. I realize that every day I inch closer to death, and I want to make it a meaningful destination, not a dreaded landmark.

F&L: How did you come up with the title and the idea for the colorful sprinkle-covered cover?

JDT: We worked really hard on finding a title for this, and we ended up landing on “Dessert First” because my mother loved dessert. She never, ever ate according to anyone’s food pyramid; she did exactly what she wanted and always ate dessert first. So it’s both a play on the colloquial idiom of “eat dessert first because life is uncertain” and a reference to my mother’s philosophy.

It’s also the idea that you should begin with the end in mind. When you do that, when you prepare for death, it makes life sweeter. You can truly savor it, because you’ve thought about the end already and you’ve talked about it with your family and friends.

When I was a chaplain, people would ask me, “What do you do as a chaplain?” and my answer was always, “I hold things.” I’m a human Tupperware container. I think if we can hold grief for each other, with each other, it makes the journey a little less hard.