Update: Jena Lee Nardella serves on the board of directors of Blood:Water.

When Jena Lee Nardella was a 21-year-old college junior, she persuaded members of the Christian band Jars of Clay to start Blood:Water, a nonprofit focused on overcoming the HIV/AIDS and water crises in Africa.

Since the founding of Blood:Water in 2004, Nardella has served as its executive director, and the organization has raised more than $27 million. From the beginning, Nardella hoped to connect concerned Americans -- starting with Jars of Clay’s fan base -- with African organizations working to bring clean water and HIV/AIDS support to 1 million people in 11 countries.

Since the founding of Blood:Water in 2004, Nardella has served as its executive director, and the organization has raised more than $27 million. From the beginning, Nardella hoped to connect concerned Americans -- starting with Jars of Clay’s fan base -- with African organizations working to bring clean water and HIV/AIDS support to 1 million people in 11 countries.

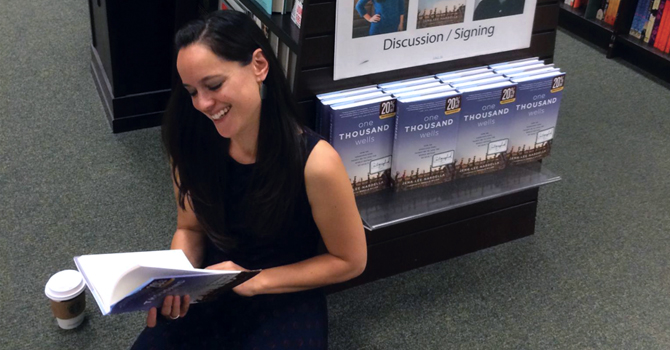

That tidy-sounding story is true, but it masks the stops and starts -- and even heartbreak -- along the way. In her new memoir, “One Thousand Wells,” Nardella recounts her journey from an idealistic college girl to the experienced Christian leader she is today. The following is an edited transcript.

Q: The subtitle of your book is “How an Audacious Goal Taught Me to Love the World Instead of Save It.” What does it mean to love the world instead of save it?

The surprise for me in writing this story was realizing that it really wasn’t about starting a nonprofit. It was so much more about this question that I’ve had to live out, which is this journey from an idealism -- wanting to believe there’s something that each of us can contribute in changing and saving the world -- to what happens when you come up against the real challenges of how hard it is to actually do such a thing.

When your idealism crumbles, what do you do with that, and how do you stay with it? Once you come to know the world -- truly come to know the world and all its doubt and darkness -- can you love it still?

I learned that the more sustainable, more responsible way to step into the world is to choose to love it, which is maybe even a little bit more heroic than trying to save it, a little bit harder to do.

Q: Talk about the idealism that fueled you in the beginning.

We were so motivated by the power of the stories that we had encountered in Africa, and so excited about being able to bring those stories back to the [Jars of Clay] fan base and really ignite response that would allow us to provide HIV and water support to these people that we met.

And it was working. It was so beautiful. It was an unlikely story of a rock band and a 22-year-old being able to actualize these ideas into something tangible.

I think the idealism is so important in the world. I’m looking back at it and realizing that a lot of the things we thought we were going to be able to achieve were not actually possible.

But it doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t step into the world or start doing this with idealism. If we ignore the idealism, then we strive for mediocrity. I think that there’s something beautiful about it, even though it’s not necessarily the most sustainable thing to hold on to the whole of your life.

Q: When did you first bump into reality on this journey?

It was when certain relationships that I had in Africa were more deceiving than I had thought -- when I came up against my own naiveté and didn’t realize that some of our funds were being misused.

It was also this encounter with senseless deaths. Some of it was losing friends in Africa in the midst of the work. Issues even as basic or simple as clean water are a lot more complex in a place that has this history of extreme poverty and oppression. There’s so much complexity to it I didn’t see when we were dreaming of the Thousand Wells project.

Q: What happened to really cause your idealism to crumble?

As Americans, many of us assume that if something needs to be done, there’s a way to do it. I was pretty convinced that if I just worked hard enough or if we just gathered enough money or mobilized enough communities, certain things would work.

The laws of return on investment don’t apply in many places around the world, and so the idealism started to crumble when my own formula of how to make change happen in the world wasn’t working.

I struggled with understanding how to still believe in a good God when people were continuing to die.

We had the economic crisis in 2008, and all of a sudden the funding that was coming to Blood:Water just shrunk. It all felt like it was crumbling. That was really the key point for me.

I had to decide whether, even if the results that I’m seeking aren’t guaranteed or may never come, is it still worth fighting for? Even if my ideas of what Africa was about or who God is or who I am in the world aren’t what I thought they were when I started, is it still worth sticking with it?

I had a really amazing mentor who basically told me that hope is not passive wishing. It’s an active exercise. For me, the greatest maturing of my own story was choosing to stay with it even when the idealism faded, and to actually make a choice to love the world even as I came to know it differently than what I had originally signed up for.

Q: So you go into it with all this excitement and idealism, and then there’s a point where you write, “We felt like fools trying to put out a forest fire with a dribble of water.”

This community and Blood:Water worked so hard to build rainwater catchment tanks in northern Kenya only to be followed by a completely unexpected season of drought. Then I realized that you can do everything you possibly can but you can’t make the rain come.

And HIV was so much more complex than we thought and came to know. What came out of it was this need to be able to be realistic about what we were facing and what we were capable of doing.

Also, we had to adjust our definitions of success. There’s this concept of “proximate justice,” which is it’s better to have some justice somewhere than no justice anywhere. This is very hard for the idealist, for the 22-year-old idealist.

But there’s only a certain part of justice that I can help move the needle on. And there’s this one place, like Lwala, where all of a sudden we could celebrate small things happening, even if it’s not everything.

Even this year, in 2015, Lwala is a place where there’s a high HIV prevalence rate, but we’ve been able to celebrate the fact that of the 97 babies who have been born to HIV-positive mothers, all 97 have been born negative. So we’ve stopped the transmission of HIV from one generation to another, at least in this one particular place.

I think that’s remarkable. And that’s something that reminds me it’s worth fighting for, even if it’s in one small space in western Kenya. It’s 97 more babies whose stories are different.

Q: How did you get to that place? You’re saving 97 babies in this one village, and yet there was that moment when you were thinking of the millions of people across the entire continent of Africa and realizing, “What was I thinking? How could I tell people we were going to change anything?” How do you develop that resiliency?

The process is actually a lot of grief. But I think that the journey has also provided a lot of freedom.

Freedom -- a recognition of a very significant role that each of us gets to play in the world but that ultimately, it’s not on our shoulders. It forces us to stay in a posture of remembering who is God and who are we.

I wanted to be the savior. I wanted to believe that I could be the one to make the rain come or to heal people. So there was grief and a good dose of humility in that recognition.

I’ve been fiercely trying to hold true to the belief that even if it’s proximate, it’s worthy of pouring my life into it. The hope is that everybody else also takes part in their proximate responsibilities, so that we can watch this beautiful weaving together of all of the small things.

God is able to knit those into something very beautiful, and it takes away the messiah complex. It offers freedom. It puts me in a posture of great dependence and hope that the God of the universe is the one who is ultimately caring for the least of these.

It allows me to pace myself in a way that is more sustainable.

Q: You alluded to this earlier, but there was another low point, when Moses, one of your oldest, closest collaborators -- someone you thought of as family -- turned out to have been mismanaging funds, betraying your trust. What about that human betrayal? Did it take a different set of skills to bounce back from that?

It was wrapped in the idealism of this belief that Africans are hardworking and compassionate and creative and capable people to address these issues that we wanted to partner with them on. That was the story that Blood:Water was called to tell -- and that’s the story we believe in today.

But what happened was, in that vision of wanting to tell that side of the story about Africa, I wrapped it in a romanticism that didn’t allow people like Moses to be human. The romanticism of partnership and committing and mutuality and all these things that were so important to me and the way that we built Blood:Water -- that didn’t leave room for the human brokenness that’s true across the board.

That experience actually showed me more about myself than it did about him. It showed me I actually did a disservice to Moses by entrenching it in the romanticism of friendship versus treating him like a partner and having accountability or having clear boundaries.

If I hadn’t been so young and naive in developing those partnerships, I would have known that certain checks and balances are really important to do no matter where you’re working in the world, whether in your own hometown or across the globe.

I realize that if I didn’t have certain checks and balances in my own life, I wouldn’t follow those rules, and it would probably harm me and others. If there’s no speed limit set, then I’ll drive as fast as I want to.

Q: Just to clarify, presumably you’re not saying you’d steal money if you were given the opportunity.

Yeah, I would hope not. But I don’t know, because I live in a culture where there are so many standards. I’ve thought a lot about it, and with Moses, I understand what it feels like to be in a position where you’ve given up a whole lot on behalf of other people.

He was a really savvy businessman who could have made a lot of money, and he was putting in so many hours and was so sacrificial, and he made such a difference in these communities. I could imagine this little mental slippery slope of, “I have worked really hard. Five dollars here, $10 there, it’s totally OK, because I’m putting a lot in here.”

And then it just -- so I could see that for myself in the same way, working 60, 70 hours a week for a nonprofit and starting to justify why a little comfort here or there is worth it because I’ve given so much. I actually was able to put myself in his shoes a little bit, or at least understand how something like that happens.

Q: It’s interesting to me how often, when you read stories of embezzlement, the story starts with people making an innocent mistake but realizing that no one caught it. Then they think, “I’ll temporarily borrow this, because I’ve got this payment due, and I’ll put it back.” And it snowballs.

I actually think that’s how it happened. I don’t think he set out to say, “Oh, a young girl -- I’m going to take advantage of her and trick her. This is going to be a great moneymaking partnership for me.” I think he is actually very grieved by the break in the relationship between us, more so than the money.

I really used to believe that everyone had the best of intentions, and I just don’t think that’s true anymore. It’s not just through my experience with Moses but also in understanding my own brokenness.

That’s a shattering reality, to have to readjust the worldview where you think you and everyone else you’re interacting with is motivated by the good. And most people certainly are, but it’s -- we’re all really broken, and so you have to take that into account.

Q: And yet even with going from this naive high to this crushed low, you’ve persevered. What advice would you give to folks who maybe are struggling with these same issues? Do you have any thoughts that you would share with them?

It’s important to evaluate what our internal definitions of success are and ask ourselves whether they give enough space for the stops and starts. Accomplishment has to absolutely mingle with failure.

Am I willing to stay with it even if I don’t ever in my lifetime get to see the fruit of the labor? In a lot of ways, for leaders, what’s challenging today is that everything around us has an instant gratification -- has an immediacy -- to it.

If we’re in the business of cultivating the kingdom in the form of lives or communities or the structure of justice or whatever it looks like, those things take time. Like I say in the book, really think about this “slowly by slowly” approach and do not be discouraged when things take longer than we expect.

I think of this example of these babies in Lwala -- that’s a success that wouldn’t have been true if I had given up six years ago. I have no idea what another 10 years in this one particular community might look like if we stay with it.

The challenge for all of us as leaders is to ask, “How are we pacing ourselves? How are we bringing people along with us to have the right kinds of expectations?” Again, to be hopeful and to have great vision for the change that we can see and the love that we can pour out, but to celebrate small steps along the way and not be dissatisfied if that big, ultimate goal isn’t reached in our lifetime.

Thirty years ago, AIDS was a death sentence. Ten years into it, it was still pretty much a death sentence for people in Africa; and 20 years into it, all of a sudden it started to change. And 30 years in now, it is a chronic disease that can be managed if people have access to the medication and the lifestyle that allows them to have healthy nutrition and clean water and income and counseling. This is a remarkable change.

I’m so grateful for the people who 30 years ago were in it, and are still in it today, and have helped shift that tide. It’s asking leaders what their 30- or 50-year hope is, and then how do you chip away at it one little moment at a time.