I had an unforgettable conversation with my son when he was little. We had gone to church for Ash Wednesday, and he had been in the toddler room while I attended the service.

On the drive home, after being quiet most of the way, my son piped up from the back seat, “Uhmma, am I gonna go to jail?”

I was startled. “No, of course not! What makes you ask that?”

“Well … the teacher said that Jesus had to die because we’re bad. And bad people go to jail!”

I was horrified.

“Oh no, sweetie! No, you’re not bad. God loves you so much! Don’t worry. That’s not what the teacher meant!”

Surely we can do better than that.

I learned about Jesus in similar ways. My teachers stressed that God loved us despite finding us inherently offensive. The church taught me about God’s grace, but it also drove home the message that God couldn’t tolerate my presence and viewed me with a kind of holy disgust. God was all light and we were all filth. God was on one side of a vast chasm and we were stuck on the other, but for the bridging work of the cross.

For some of us, those kinds of images amplified a sense of punishing distance from God that we already felt too keenly. They reinforced fears that we might be irredeemably lost, too appallingly bad to be reached by any kind of bridge. I never had any trouble believing that I was a wretched worm before God. That came easily. What seemed impossible was that God could ever truly love a worm like me.

My faith has always been riddled with doubt. I tend to feel life intensely, all the way down to my bones. My joys are plentiful and bright, but I struggle often with depression, with chutes into despair.

And because of my inconstant faith, I used to be plagued by fears that I simply wasn’t built to meet the basic conditions for God’s acceptance. Despite my experiences of God’s love, a background hum of existential terror accompanied my hopelessness whenever I got depressed. I worried that Christ’s work notwithstanding, I might be stuck galaxies away from God, beyond the reach of mercy.

Sometimes in depression, I feel that I’m sunk in the darkness of a very deep ocean. It used to be that at those depths, all was muffled except the voices that said God couldn’t stand me for how faithless I was. Voices that told me I was a lost cause and an utter disappointment to God.

I don’t believe that Jesus meant for our stories about him to spur such haunting terror or self-rejection.

While all our metaphors are imperfect and can only clumsily gesture toward divine mysteries, the ones that insist on humanity’s wretchedness and distance from God can inflict lasting wounds. They can cloud our belovedness and the reality of “God with us.”

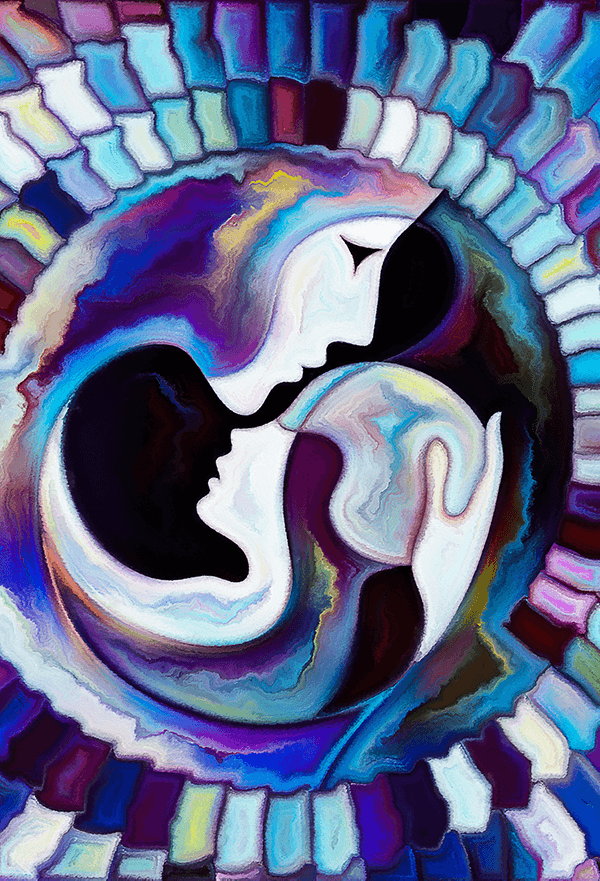

Some of us need new metaphors that don’t diminish the truth of God’s unrelenting love. I’ve personally had to let go of many old images I grew up with. Now I try to see myself not as originally repulsive and separated from God by a vast gulf but as born of love and held close in God’s mother-heart.

We find images of God’s maternal heart and nearness throughout Scripture. We see the mother-heart of God in how Jesus went out of his way to feed and heal people, and how he welcomed little children.

We see God receive all of Job’s cries — chapter after chapter of complaints against God. And what does Job get for his brazen challenges? He isn’t zapped into oblivion. He’s granted a conversation with the Almighty, albeit a humbling one.

I see God’s mothering presence in the story of Elijah, when he feels so defeated that he wants to die. Elijah doesn’t get a rebuke about how he should have more faith or count his blessings. God comes to him gently in a mama-like angel with freshly baked bread and a pitcher of water.

Isaiah renders God’s love for us as even more doting and steadfast than that of a mother for a baby at her breast. The psalmist speaks of God as so inescapably near that there’s nowhere on earth he could go to get away from God if he tried.

That’s the kind of Savior I need. One driven by love to chase me to the ends of the earth and the far side of the sea.

These days when I find myself in the oceanic depths, I’m less alarmed by the darkness and silence there. It’s a bit quieter than it used to be. I’m less hounded by voices proclaiming God’s rejection. I see glimmers of Christ-light here and there in the abyss.

I feel alone but find that I’m not alone. Impossibly, I find myself breathing underwater. I notice that I’m held somehow — breath by breath, as if nestled in the very womb of God.

Lent is a time when we can contemplate the tender closeness of Christ with us in our “helpless estate,” through every kind of suffering, no matter how wavering our faith, and no matter how dark our darkness.

In this season, we reflect on how God saw us in pain and became “a man of sorrows, acquainted with grief” for our sakes. Jesus on the cross joins us in our despair of feeling abandoned by God.

Christ doesn’t always calm the storm when we’re at sea on a sinking boat, but our Savior would rather sink into the depths with us than ever leave us alone. Even if we find ourselves living at the bottom of that sea — why, there he is, still with us.

That’s the core truth of the gospel. It begins not with our badness but with God’s unshakable love. The hope of this season is that our God, upon seeing us drowning, came close to be with us through it all.

We find images of God’s maternal heart and nearness throughout Scripture. We see the mother-heart of God in how Jesus went out of his way to feed and heal people, and how he welcomed little children.