In the early 2000s, Mark Charles moved with his family to live in a traditional hogan, a single-room home with dirt floors and log walls, among his people in the Navajo Nation. Trading the density of Denver, Colorado, for the wide-open space of a sheep camp some 6 miles from the nearest paved road, Charles and his family were isolated.

“It literally felt like we dropped off the face of the earth,” Charles said.

But beyond the geographic isolation, Charles felt his marginalization as an indigenous person even more sharply. Joining the community in the Navajo Nation, he saw how being placed on the margins of land was also a way of being placed on the margins of society.

“We quickly learned that the primary groups of nonnatives who come to Indian reservations are those who come to take your picture or those who come to give you charity. And neither come to build a relationship with you,” he said.

During this time, he came across the book “Pagans in the Promised Land,” by Steven Newcomb, which describes the effect of the Doctrine of Discovery on indigenous people. As he wrestled with the modern-day marginalization in the Navajo Nation, Charles saw more clearly than ever the historical trauma of viewing the Americas as the New World.

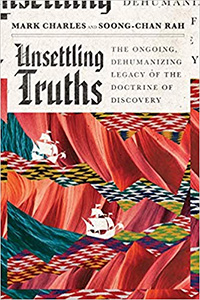

It’s to this disturbing legacy that Charles speaks in his book “Unsettling Truths,” co-written with Soong-Chan Rah. The project is a reckoning with the history and theology of the Doctrine of Discovery and a call for repentance for all living on stolen land.

Charles is an activist, speaker and former pastor. He has served as a correspondent and columnist for Native News Online and now lives in Washington, D.C.

Charles is an activist, speaker and former pastor. He has served as a correspondent and columnist for Native News Online and now lives in Washington, D.C.

He spoke about the book and what true repentance for stolen land looks like with Faith & Leadership’s Chris Karnadi. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: Can you explain the Doctrine of Discovery and its lasting impact?

Mark Charles: The Doctrine of Discovery is a series of papal bulls, or edicts, of the Catholic Church. The first one, from 1452, is titled Dum Diversas, written by Pope Nicholas V. It authorized the Portuguese to “invade, search out, capture, vanquish, and subdue all Saracens and pagans, … reduce their persons to perpetual slavery, and … convert them to … their use and profit” [as detailed in the follow-up Romanus Pontifex of 1455].

It’s the church in Europe saying to the nations of Europe, “Wherever you go, whatever land you find not ruled by white European Christian rulers, those people are subhuman, and their land is yours to take.”

So this was adopted by European nations both [in efforts] in Africa to colonize and enslave people and by Columbus to land in this “New World,” which is already inhabited by millions, and claim to discover it. You cannot discover lands already inhabited. That’s called stealing. The fact that we refer to what Columbus did as “discovery” reveals the implicit racial bias, which is that native people, people of color, aren’t fully human.

So then this doctrine gets imbedded into the foundation of the country. The Declaration of Independence, which begins with the words “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” refers to natives as “merciless Indian Savages” 30 lines later, making it clear that our Founding Fathers used “all men” with a very narrow definition of who was actually human.

The Constitution begins with the words “We the People.” Article 1, Section 2, which is the section that defines who is included in the Constitution and never mentions women, specifically excludes natives and cuts Africans to three-fifths of a person. “The People” is loosely defined in the Constitution as white, land-owning men. That’s who could vote at the time.

In 1823, the Doctrine of Discovery gets referenced by John Marshall in the Supreme Court in Johnson v. McIntosh and basically states that the principle for land titles is discovery. According to the doctrine, natives were here first, but because we’re savages, we only have the right of occupancy to the land, while Europeans have the right of discovery, and therefore they’re the true title holders.

So that case, along with a few others, creates the legal precedent for land titles. And that precedent and the Doctrine of Discovery are referenced specifically by the Supreme Court in rulings in 1954, 1985 and, most recently, 2005.

F&L: How should Christian leaders be talking about the Doctrine of Discovery? How should they be reacting to the Doctrine of Discovery?

MC: There have been many denominations and individuals who have repudiated the Doctrine of Discovery. They’ve condemned it as heresy. There have been a lot of examples of denominations and leaders taking a very public stance of denouncing this doctrine.

The challenging part -- and I actually warn people to think very carefully before they repudiate the Doctrine of Discovery -- is that it’s not just a theological action. The Doctrine of Discovery has become a legal instrument. And it’s the instrument that props up land titles. So if you are going to repudiate this doctrine but are not willing to give up your land, whose title is based on this doctrine, then you probably shouldn’t repudiate it.

At Standing Rock -- and this story is in the book -- there was a large public gathering of Christians who repudiated the Doctrine of Discovery. And I was there a few weeks later and asked the people who organized it if they got any land back.

No, they didn’t.

Well, did they commit that they would not defend themselves in court if they were sued in court for the land?

No, they didn’t do that either.

Oh. Well, this was just a photo-op, then. If you’re going to repudiate a doctrine that doesn’t just have theological or even moral implications but also legal implications, then your repudiation has to have legal implications as well.

And if you’re not willing to own that, then please don’t repudiate it. Just embrace the fact that your nation, and your church, is unjust. That’s the only alternative. If you’re not willing to actually repent of what this doctrine has done, then don’t pretend to condemn it. If you’re not willing to begin to look into or give up how you have benefited from this doctrine, then it’s not real repentance.

F&L: How do you think reading this book will push people toward that real repentance?

MC: The book started out a long time ago when Soong-Chan and I met through some projects we were doing together. He was finishing up his book called “Prophetic Lament,” and I was talking about the Doctrine of Discovery. We had a common theme of lament.

I was calling the church into a season of lament regarding our history with both writing and being complicit in this doctrine. And he was talking about lament from his book. So we started to write. And then the 2016 election happened, and we had to sit down and rethink some of our theses. The book took on a bit more of a rebuking tone than even a call to lament. It was still a call to lament, but it was even more of a rebuke.

I was calling the church into a season of lament regarding our history with both writing and being complicit in this doctrine. And he was talking about lament from his book. So we started to write. And then the 2016 election happened, and we had to sit down and rethink some of our theses. The book took on a bit more of a rebuking tone than even a call to lament. It was still a call to lament, but it was even more of a rebuke.

I feel very good about the book right now. I feel it’s a strong book and a very honest book. I think it’s hopeful, not in this warm-and-fuzzy hopeful way, but in the sense that I think it helps the church open its eyes to some of what we believed in the past and how that has led to the challenges we’re facing in the present -- and then what we need to do to address those things.

F&L: Thank you for sharing those thoughts. They’ve challenged me and made me uncomfortable in the best way.

MC: That’s our goal. Trust me, both Soong-Chan and I felt very uncomfortable even as we were writing it. One of the reasons it took so long to write is because there were several points where I realized I was believing some of these same lies I’m exposing.

I had to pause, even sometimes for months at a time, and just lament what I was learning and allow that to shift my paradigm some more as we continue to understand this history and move forward.