It has been said that Jesus promised his disciples three things: that they would be completely fearless, absurdly happy and in constant trouble, notes scholar William Barclay.

In today’s troubling times, we need to listen to Jesus -- and to the wisdom of the Hebrew biblical-prophetic tradition from which Jesus emerged.

The Bible is a book about embodying and enacting freedom -- liberation from hatred and violence, suffering and sin, oppression and injustice. In our nation today, that means working to liberate people from poverty, racism and white supremacy, among other ills.

In the Bible, the liberation theme begins 1,200 years before Jesus, with the exodus of the Jewish people from enslavement in Egypt. That story became the template and metaphor for the entire Bible -- an inner journey of personal liberation and an outer journey of social justice.

As Richard Rohr says, “Spirituality and action are connected from the very beginning and can never be separated.”

Moses is the person at the heart of the freedom march out of bondage. We often forget that Moses is a murderer on the run. He has escaped from Egypt, lonely and fearful, and sees “a bush that burns but is not consumed” (Exodus 3:2).

Here, he is broken open. He has been through failure and suffering, which is often what it takes to crack us open -- so the light can find us, as the Quakers say.

And when the light finds him, a voice, a divine leading, speaks to him: “Go, tell Pharaoh to let my people go.” The voice does not tell Moses to go build a temple or go to church. It says, “Go, liberate my people.”

The fascinating thing about the story, to me, is the combination of mysticism and call, of contemplative experience and action for justice and freedom.

Moses has an internal experience, a direct experience of the Holy One. Out of that inner experience emerges his action for liberation. He is transformed!

I submit that this is the basic pattern and path for all of us. Our spiritual awakening tends to happen when we are broken open by some deep experience of suffering or love. Only when we’re cracked open can the light get through.

And then, to quote Colin Morris, we can “take hold of the near edge of some great problem and act at cost to ourselves.”

In this time of turbulence and racial unrest, what implications does Moses’ experience have for you and me? I want to explore this question through the witness of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, who in later years had the unique title of professor of Jewish ethics and mysticism at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York.

In a 1963 speech at the National Conference on Religion and Race, Heschel said that the main participants at the first such conference were Pharaoh and Moses:

“Moses’ words were: ‘Thus says the Lord, the God of Israel, let my people go. …’ While Pharaoh retorted: ‘Who is the Lord, that I should heed this voice and let Israel go? I do not know the Lord, and moreover I will not let Israel go.’”

The outcome of that first meeting, Heschel said, is still playing out in our time: “The exodus began, but is far from having been completed. In fact, it was easier for the children of Israel to cross the Red Sea than for a Negro to cross certain university campuses.”

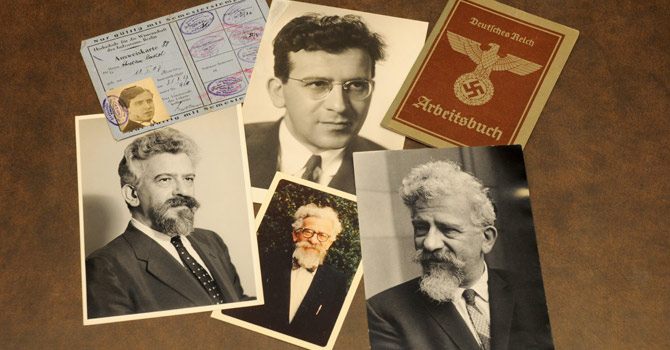

Like Moses, Heschel was transformed by suffering. Heschel grew up immersed in Hasidic Judaism, the contemplative dimension of Jewish tradition, as well as the vigorous ethical demands of the Hebrew prophets.

He escaped Nazi Germany, where his mother and sisters were murdered, and he turned to his inner light, the shekinah that became his inner leading to join the movement for liberation and justice.

Heschel came to the U.S., where he was keenly alert to the ugly parallels between Germany’s treatment of the Jews and America’s oppression of blacks, especially in the South.

He opposed U.S. racism as “unmitigated evil” and became involved in the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements. In the iconic pictures of the march to Selma, Alabama, we see the white-bearded Heschel walking alongside the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Heschel’s writing is laced with poetic impatience: “radical amazement,” “a fellowship with the feelings of God,” “the ineffable,” “spiritual audacity,” “the monstrosity of inequality,” “the evil of indifference,” “the urgency of justice.”

Heschel says that God identifies God’s self with the misery of humans. In other words, when we suffer, God suffers with us.

Likewise, when God suffers, God needs us to feel God’s anguish and help alleviate God’s pain. God needs us!

We are, as Heschel says of the prophets, “in sympathy with the divine pathos.”

Heschel wrote much about the “pathos of God,” and he allowed that pathos to stir him; he allowed his personal grief, his suffering and the anguish of the prophets to ignite his conscience and propel him into action.

In 1963, as racial unrest was escalating, Heschel sent a telegram to President John F. Kennedy, urging that he declare a “state of moral emergency” and implement a “Marshall plan” to aid disenfranchised African-Americans. His message ended: “The hour calls for moral grandeur and spiritual audacity.”

We hear in Heschel echoes of Moses’ spirit, as well as Jesus’ call to liberation in his first sermon, quoting a fiery Hebrew prophet: “The Spirit of the Lord … has anointed me to bring good news to the poor … [and] proclaim liberation to the captives” (Luke 4:18, quoting Isaiah 61:1).

Our biblical witness and Heschel’s life raise some urgent questions: When life cracks us open -- whether from moral pain or deep personal suffering -- are we allowing the light to find us?

And when the light permeates our inner life and outer journey, will we go to a quiet place and listen for the inner leading?

Will we be attentive to the leading that calls us out the church door to a mission of liberation?

We live now -- again -- in a troubling, dangerous time. We see all around us the constant trouble that Jesus promised us.

Do we have the moral grandeur and spiritual audacity to confront it?