A world made out of love: Creation

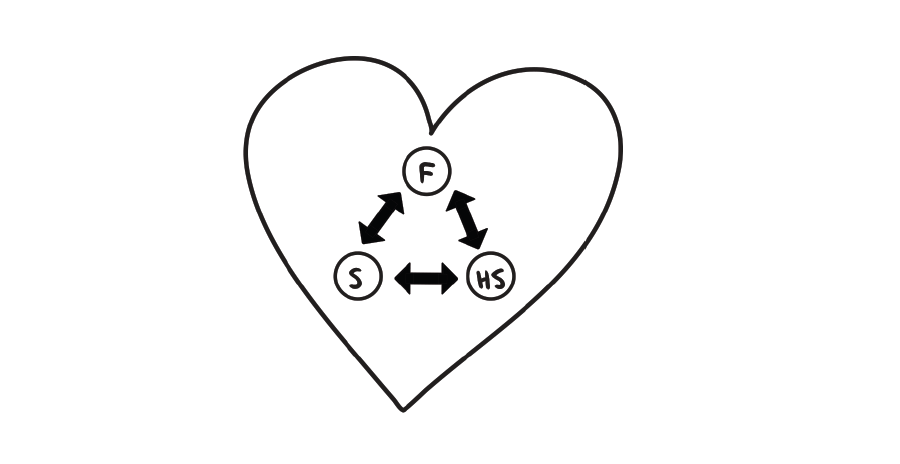

When we talk about the Trinity, we talk about love: the three persons of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in an ever-moving, ever-giving dance of love.

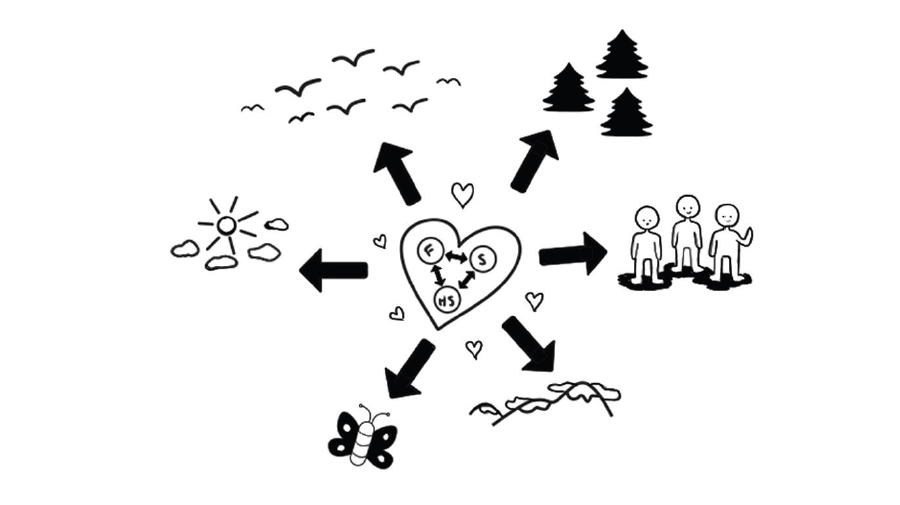

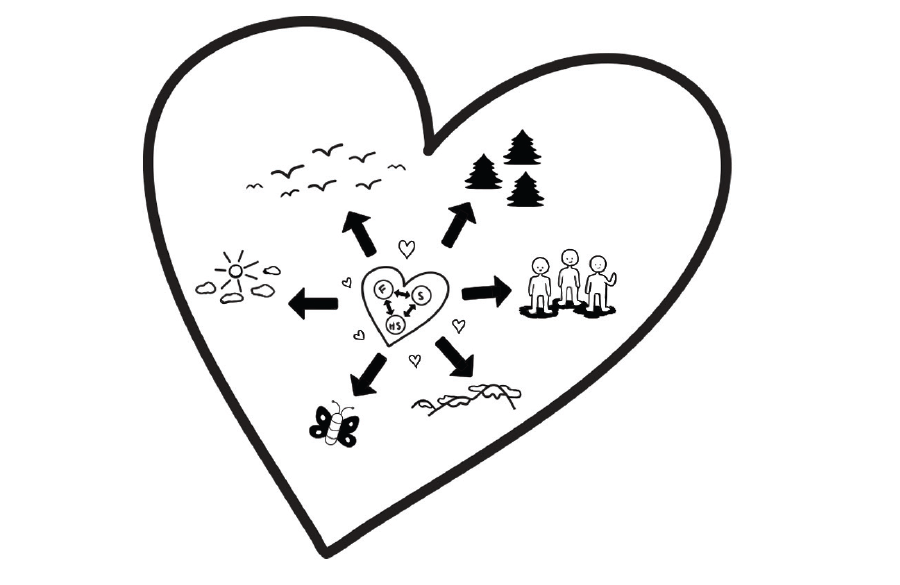

When we talk about creation, we also talk about love: the love amongst the three persons that spilled out into sun and sea and you and me.

Theology has a couple different terms to talk about these loves and how the Trinity works in relation to itself and in relation to what has been created.

When we think about that dance of love that Father, Son, and Spirit spin and move in, the inner life of these three persons, we are thinking about the immanent Trinity. When we say “immanent,” we mean “internal,” “innate,” “inside.” This is a pretty mysterious concept, because there’s only so much we can know and say about what goes on inside the Godhead apart from what we can see in the world around us.

But we can say a few important things. The apostle John put it neatly in his first letter to some early Christians: “Whoever does not love does not know God, for God is love” (1 John 4:8). God does not simply have love, or give love. Love is not simply an attribute of God; it’s God’s whole being.

And God chose to allow that love to burst out of God’s very own self.

‘When God began to create the heavens and the earth …’

This is where we begin to see the economic Trinity at play — the Trinity in its relation to what is not God, in relation to what God has created. God could have chosen to just remain as the immanent Trinity forever, having nothing to do with that which is not God. The love flowing freely between the persons of the Trinity would have been enough for God. Father, Son, and Spirit were not sitting around sulky, moping, in need of praise and adoration.

Creation wasn’t necessary.

Our world did not need to exist. Everything we see and smell and taste is excessive: an outpouring of God’s love. God didn’t need to create humans or frogs or planets to satisfy some whim or to appease some lack. God didn’t need us.

But God wanted us.

There’s a phrase attributed to St. Augustine: Amo; volo ut sis. Translated from Latin, it reads: “I love you; I want you to be.” Imagine, for a moment, God whispering this as the heavens and the earth began to take their shape, as Adam was formed from the dust and breathed into life. “I love you; I want you to be.”

God needs nothing — but God wants us to be. And in creation, God wanted to share the love that is God’s own self and being. In creating, the love within the Trinity flooded over into every nook and cranny of the cosmos, every inch drenched in it.

‘… the earth was complete chaos, and darkness covered the face of the deep …’

So God didn’t need to create, but God chose to, freely. That’s a statement we need to make when we talk about creation. There’s another piece to it, though: that God created out of nothing.

When we humans “create,” we use paints, bricks, computers, thoughts in our minds: things that already exist. When God created (in the truest sense of that word), God used … nothing.

The term theologians use to describe this concept is (you guessed it) a Latin phrase, creatio ex nihilo, which translates to “creation out of nothing.” This sets God apart from any one of us, and it sets God far beyond the reaches of any technology or tool we might develop. Only God can take nothing — a void of voids — and create.

The scholar Janet Soskice puts it like this: “Creatio ex nihilo affirms that God, from no compulsion or necessity, created the world out of nothing — really nothing — no preexistent matter, space, or time.” This concept of “really nothing” is essentially impossible for us to fathom. How can we imagine this kind of emptiness? What creatio ex nihilo does is force us to confess just how transcendent, just how “other,” God is.

But it also shows us another key thing about God.

Many centuries ago, in an English town called Norwich, a woman lived inside a church.

The woman, who became known as Julian of Norwich, lived the life of an “anchoress,” voluntarily secluding herself in a cell within the church walls so she could devote herself to prayer and worship.

She spent many years there, sifting through and making sense of some remarkable things that had happened to her. She wrote a book, “Revelations of Divine Love”— the first book written by a woman in the English language — about a series of “showings” she had received from God during a severe illness. These showings were often dramatic and graphic, showing the suffering Christ in vivid detail, but one of them included a simple image.

And in this vision he also showed a little thing, the size of a hazelnut, lying in the palm of my hand, and it was as round as a ball, as it seemed to me. I looked at it and thought, “What can this be?” And the answer came to me in a general way, like this, “It is all that is made.” I wondered how it could last, for it seemed to me so small that it might have disintegrated suddenly into nothingness. And I was answered in my understanding, “It lasts, and always will, because God loves it; and in the same way everything has its being through the love of God.”

God is transcendent and “other,” yes. But God also knows us and sustains us in a profound and personal way. This is not a watchmaker God that some philosophers have spoken of: a God who puts together a watch and then steps back to let it tick away. God is not aloof. We last because God loves us. We couldn’t exist without that love — the enveloping love of a God who is both utterly beyond us and beside us.

To emphasize that God sustains us and all of creation, theologians often reference the idea of creatio continua, another fancy Latin phrase that means that God constantly upholds all of creation.

God did not simply, at one time, desire to create the world. God always wants the world; he consistently calls what he made “good.” God actively re-creates the world in every single moment. God always wants us, and everything, to be.

What happens when we start to forget some of these ideas about creation?

Much of Christian theology ends up being centered around the person and work of Jesus Christ — which makes sense, considering the name “Christian.” The attention we give him is well-deserved, after all. But sometimes the way that focus plays out results in some long-term damage — like when the doctrine of creation starts getting squashed.

A weak theology of creation is bad news for creation. If we focus so much of our energy on ourselves as humans, on what God has done for us, and we don’t pay much attention to the rest of the universe that God made, we end up staring at a tiny piece of the big picture that is God’s love and care for the world.

A Native American theologian named George Tinker knows this all too well. He writes about the ways Christian missionaries preached the gospel to Native Americans, giving it the usual Western-church spin of humanity’s fall from grace, their sinful nature, and their need for redemption. For traditionally oppressed and marginalized peoples, however, the emphasis on humanity’s sin and their need for a savior doesn’t sound like the best news. “Unfortunately,” Tinker writes, “by the time the preacher gets to the ‘good news’ of the gospel, people are so bogged down … in [their] internalization of brokenness and lack of self-worth that too often they never quite hear the proclamation of ‘good news’ in any actualized, existential sense.”

Tinker calls for us to start sharing the good news from, well, the beginning of it all: that first “in the beginning.” He asks for us to “take creation seriously as the starting point for theology rather than treat it merely as an add-on to concerns for justice and peace.”

When we begin to neglect the significance of creation — what it says about God and God’s love — we can find ourselves getting so wrapped up in our own lost-ness and need that we forget just how loved we have always been, just how valuable everything and everyone around us is. When our theology becomes centered on “just Jesus and me,” our sisters and brothers — our whole planet — suffers.

What might it look like to take creation seriously, then — to remember how God holds us tight and close, wanting us to be?

What might it look like to remember that we live in a world that God wants?

God’s creation is vast and expansive. God does not choose to be God only for God’s own self — God is the One who delights in extending love and life to others. God’s good world — created and sustained by God’s loving-kindness — is worth knowing and celebrating and protecting.

Luckily for us, God chooses to reveal to us more of what we, creation, and God are like. That’s what we’ll look at in the next chapter.

From “Napkin Theology,” by Emily Lund and Tyler Hansen. Copyright © 2023 by Emily Lund and Tyler Hansen. Excerpted by permission of Wipf and Stock Publishers. All rights reserved.