Discernment can be a hopeful and liberating spiritual process, a means by which the Spirit can guide us toward the kind of meaningful life found when our calling, our passions, our gifts, our commitments and our responsibilities align.

When we are in the midst of it, though, discernment can also be a befuddling, exasperating and all-consuming endeavor. It can feel as constraining as it does freeing -- as if the world, suddenly expanding with new possibilities, is at the same time contracting with newfound focus.

A significant number of participants arrive at Leadership Education at Duke Divinity programs discerning vocation.

Many are at personal or professional junctures. They have left one type of ministry to begin another. They have celebrated a milestone in their ministry -- five years, 10 years, 30 years. They have recently experienced the death of a parent or a mentor, the birth of a child, the celebration of a wedding.

At these junctures, life is prompting them to ask new questions about their future and the sustainability of their vocation. They are seeking ground that feels both firmer and more faithful.

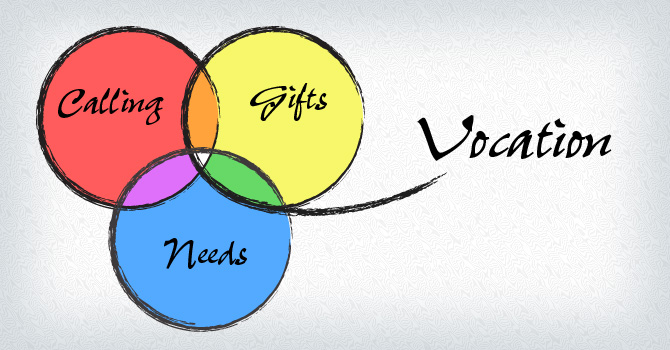

In a recent session of Foundations of Christian Leadership, I found myself telling the group that vocational discernment is really an ongoing inquiry in three directions. I am not sure where I first heard this (it isn’t original to me), but it has stayed with me across the years as a helpful frame for professional discernment.

First, you must ask, what do you feel called to do? Where do you sense the leading of God in your life? What is the kind of work that feels right and enriching for you? Where do you find meaning and purpose? Whom do you feel called to serve?

Next, you must ask, what work are you gifted to do? Think about your native gifts, as well as the skills and talents that you have cultivated along the way. Do you have great interpersonal traits like empathy and intuition? Are you great at budgeting and analyzing data? Are you a gifted communicator who can inspire and inform? What are your gifts and talents?

Finally, what work does the institution need to do? Whether you are presently employed by an institution or are imagining employment in an institution in a particular role, it becomes important to understand what the institution would ask of you. How important is interacting with the public? Is preaching or teaching ability important? Is the work solitary or team-based by nature? Is it detail-oriented or big-picture-focused? Is the work creative or analytical?

Once you have a sense of your answers to these three questions, then you look for the overlap between them. Ideally, all of us would work at the precise nexus of our sense of calling, our understanding of our gifts and the needs of our organizations.

For most of us, though, these three circles never quite align perfectly.

There is some element of our calling that our institution or our role can’t enact; there is some need of the institution that isn’t our gift but is our work. This lack of alignment causes some discontent but can also lead us to a place where we are learning and doing new things that are eventually rewarding. But when the lack of alignment is so great that our discontent devolves into unhappiness, we know it is time for us to seek something else.

The difficult exercise of reflecting on our calling, our gifts and our institution’s needs is one we often resist engaging.

As good stewards, however, we cannot postpone it. It is part of our responsibility. It is part of our faithfulness. We must not wait until the symptom of unhappiness presents itself to ask about the alignment of our souls and roles.