Pauli Murray labeled herself America’s “problem child” for good reason. Murray spent her life attempting to correct flaws and, through religious and social agitation, humanize life. In our troubled times, Murray’s theologizing in sermons and lectures provides wisdom and insights that might serve to help bridge the distance between pain and prosperity — hard times and hope.

Murray proposed a theological perspective that was pro-African American and pro-woman yet concerned with the dangers of particularization as they related to a limited perspective on the nature of oppression and righteousness. She believed that human dignity and progress could be achieved through nonviolent direct action and persistent critique of social ills. In many ways Murray was opposed to what she considered the generally exclusivist agenda and tone of Black theology of the early 1970s as articulated by theologians James H. Cone and Albert Cleage. She considered the anger shadowing such work as an unnecessary strike against its utility and creativity.

Despite her disagreement with thinkers such as Cone and Cleage, Murray held a strong appreciation for theologian J. Deotis Roberts, whose push for simultaneous attention to liberation and reconciliation mirrored her sense of how human dignity is best developed and nurtured.

While Black theology’s rhetoric gained some attention, the lack of a clearly defined and organizing ideology did major damage to its push for social justice. Social justice had two platforms from which it developed for Murray: nonviolent direct action and universal human rights. But Black theology did not fully recognize the web of oppression and spoke only a limited (and limiting) word to suffering humanity. This limited word was based on the Christ event, which demonstrated God’s primary commitment to those who are suffering. What was missing from this stance, according to Murray, was attention to universal issues of human rights. As I’ve noted elsewhere in relationship to Murray on this point, it was much too focused on African Americans to the exclusion of a realization of how the plight of African Americans connected to the misery of the oppressed across the globe.

Murray made an effort to ease unhealthy tension between what many white and Black Americans understood as competing interests. Recognizing the weblike nature of oppression, she suggested a theology of relationship through which the formation of complex and democratic community became the goal of ministry and social activism. From her perspective, a proper response to God is inseparable from attention to human need. In either case, one is required to engage fully, to risk oneself through connection to others. The Christian’s obligation involves fostering healthy and harmonious relationships within all spheres of existence. Christians are able to accomplish this task of right relationship through a recognition of “transcendent power” above and beyond us that works within the context of human history. As Murray would reflect in her convocation speech at the University of Florida, these are the rightful consequences of the Christian’s understanding that humans are made in the image of God, with certain rights that must be respected and protected. Exclusionary tendencies troubled her, regardless of the form they took. Murray pushed beyond history as the framework for theological thinking, and in its place suggested sensitivity to “her-story.” This effort to look behind patriarchal constructions of meaning also involved rethinking the church in order to recover its more justice-minded elements. This theological synergy must have seemed obvious to her because over the course of her life, tension and paradox had allowed for creative possibilities, for fruitful engagement.

Although they were vital movements toward religious and social betterment, neither feminist theology nor Black theology spoke sufficiently to the experiences of African American women, who suffered because of their race, gender, and class. Black male theologians approached “women’s issues” with suspicion, and feminists held a rather provincial conception of the community of women. In both cases, theological thinking was devoid of creative tensions and complexity, and for Murray this was deeply problematic in that it entailed a misconception of life and the struggle for full humanity. Keeping to this narrow agenda, both forms of theological discourse missed the uniqueness of African American women.

It was this theology of relationship, a commitment to the full expression of our capacities, that urged her to confront a sexist church and a sexist civil rights movement. To deny women full access to the life and work of the church was to deny a vital dimension of the gospel’s power and to stifle the Christian faith’s ability to transform our collective circumstances. Such injustice can’t be covered by theological and doctrinal pronouncements. Murray would turn theological discourse, shift ethical language, so as to urge us to be our best. And Murray didn’t demand of others any more than she demanded of herself as activist, attorney, professor, and minister.

Through the power of God and human talent, according to Murray, ministry bridged spiritual and physical reconciliation. A commitment to rights is only fulfilled through grace — an extension of this commitment beyond the physical to the inner life. Reconciliation in either form (spiritual or physical) has to involve a sense of proper relationship — humanity humble before God, and the development of human relationships based on compassion and respect. As she would reflect in several of her writings, this for Murray entailed ministry extending beyond traditional responsibility for a pulpit.

Murray believed issues such as sexism and racism were fundamentally moral and spiritual issues that could not be addressed strictly through mundane means of jurisprudence. Theological training and ordained ministry only enhanced her commitment to nonviolent direct action as a way of life, one with deep moral and ethical implications. Murray was committed to an activist faith, a recognition that religion at its best is “this-worldly,” committed to the application of the gospel to historical change, salvation as the transformation of societal existence.

In essence, Murray took the critique of racism from Black theology, the critique of sexism from feminist theology, the general appeal to the gospel as an agent of social change from the Social Gospel (i.e., Martin Luther King’s theological orientation), and her life experience to foster a theological platform that was pro-Black, pro-woman, and concerned with the dangers of particularization.

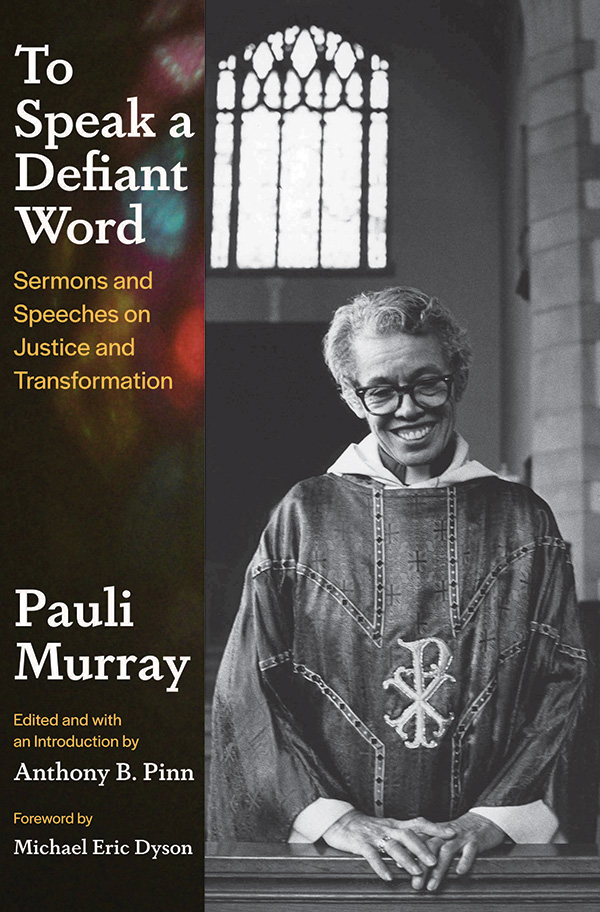

Excerpted with permission from Anthony B. Pinn’s editor’s introduction in “To Speak a Defiant Word: Sermons and Speeches on Justice and Transformation,” by Pauli Murray, ed. Anthony B. Pinn, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2023.

Murray was committed to an activist faith, a recognition that religion at its best is “this-worldly,” committed to the application of the gospel to historical change, salvation as the transformation of societal existence.