I’ve heard the words so often lately, I’ve learned them by heart.

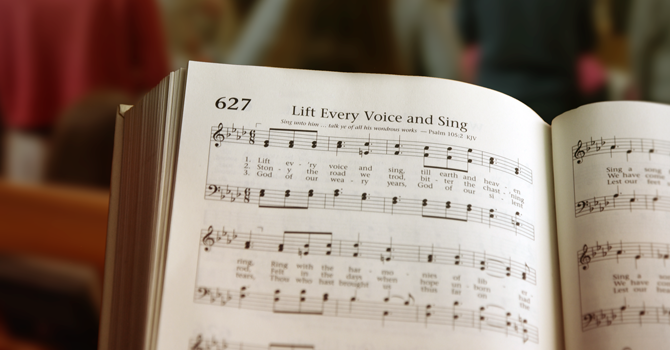

Lift every voice and sing

Till earth and heaven ring,

Ring with the harmonies of liberty …

In Episcopal circles, the song known as the Black national anthem rings out at celebrations of saints like Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, Henry Beard Delany and Pauli Murray. Friends of mine recently included it in their wedding. As with any song in the hymnal (“Lift Every Voice and Sing” is included in many of them), some members of the congregation know it better than others. In this case, familiarity breaks down along racial lines.

Most people who can sing the anthem by heart are Black; they often have learned the words from their families and community, in church and civic celebrations.

A few are like me: white people who committed to memorizing the lyrics. (It doesn’t take long; a melody that alternates between soaring notes and a marching tempo drives home both the words and the emotions behind them.) Others were introduced to the song when Beyoncé sang it at Coachella as the first African American woman to headline that music festival, in 2018.

Most white members of the congregation, however, can only summon the first couple of lines or hum the tune.

The opening is a beautiful invitation anyone can belt out with gusto. But the next verse is more challenging:

Stony the road we trod,

Bitter the chastening rod,

Felt in the days when hope unborn had died …

At this point, I’m usually looking around the church, deeply conscious that some in the congregation are descended from people who trod the stony road of slavery -- a way, as the lyrics say, that was watered with tears -- on toward emancipation through “the blood of the slaughtered.”

Others’ ancestors held those people in slavery. Many are descended from both groups (a fact usually not acknowledged by the white branches of their family trees).

Some of us are immigrants: many, like me, benefiting from the white privilege that the Civil War’s torrents of blood did not wash away, others targeted daily by the shape-shifting demon of racism.

Every time, these thoughts leave me singing through tears. They’re not so much tears of mourning for the past -- although the lyrics attest that there is plenty to lament -- as tears of shame for the present. And they’re also tears of wonder: wonder at the grace my Black siblings in Christ show by continuing to stand, sing and worship with people who so often close our ears to the song’s present-day call.

It takes grace to continue to cooperate when white members of your denomination lament the closing of historically Black churches without acknowledging the historic lack of investment by the larger, predominantly white church, or the Jim Crow laws and customs that made those churches financially vulnerable.

It takes grace, at the denominational annual meeting, to exchange a sign of peace with the person who earlier mistook you for one of the conference center’s waiters and now doesn’t even recognize you from that incident.

(True stories.)

And, I realize, it takes grace to continue to sing along to “Lift Every Voice and Sing” next to the white woman whose eyes are brimming with tears without telling her to get over herself and dry it up.

I thank God for the grace my Black friends extend to me and to the church. I know it’s born of faith in God who, as the poet and author of the anthem, James Weldon Johnson, wrote, “hast brought us thus far on the way” and “hast by thy might led us into the light.”

Johnson wrote those words at the turn of the 20th century, an era historians call the “nadir” of African American history. By forcibly seizing political power and organizing armed squads to terrorize Black citizens, white supremacists were doing everything they could to extinguish the light of hope that emancipation and Reconstruction had kindled.

And yet African Americans were forming civic organizations, weaving networks of mutual aid and flourishing in the face of white violence and its pallid but no less pernicious cousin, white indifference.

As the scholar Imani Perry has written in her history of the anthem, Johnson “told the story of Black life in terms that were epic, wrenching, and thunderous” to acknowledge his people’s heartache and to honor both their beauty and their longing for a transformed land where Black people could live without fear.

These days, my church and other predominantly white denominations talk a lot about our yearning to live in peace with all people. We repeat our desire for reconciliation, to bridge the divide between white Christians and, especially, our Black siblings in faith.

But it’s hard to weave those bonds of fellowship when those expressing a longing for unity know so little about the “stony road” the others have trod, refuse to acknowledge the benefits won for themselves by the “chastening rod” (benefits that persist over a century later), and fail to ask how they might, in specific and material ways, start to atone.

That’s the flip side to grace: sin. When black members of Christ’s body offer grace to their white siblings, they are imitating Christ. But when white Christians remain willfully blind to the fact that we have received a gift, when we don’t let grace spur us to repentance, we are persisting in sin. And without repentance and a commitment to atone, reconciliation is impossible.

It’s a cliche to say that racial reconciliation is not about holding hands and singing “Kumbaya.” It is not about learning the words to “Lift Every Voice” either. But if white Christians are going to continue singing about the power of God and the grace of the gospel, we would do well to ask: What actions would begin to show our black siblings in faith that this message has truly touched our hearts?