If a fanatic is someone who won’t change either his mind or the subject, then Bishop Thomas Lanier Hoyt Jr. says you can call him a fanatic for ecumenism.

“I won’t change the subject about what it means to have relationships with other denominations, other people and humanity,” Hoyt said. “It’s not just churches. Ecumenism is how you deal with human beings of all persuasions, which means that one has to be open to people who don’t have the same ideas.”

Hoyt is the senior bishop of the Christian Methodist Episcopal (CME) Church, presiding over the East Coast region for the 141-year-old historically African-American denomination. Long before his 2010 appointment to that post, he was known as a scholar and a leader in the Christian ecumenical movement.

A former president of the National Council of Churches, Hoyt has written more than 40 articles for professional journals and publications, and he delivered the Lyman Beecher Lectures at Yale Divinity School in 1993. He was a professor of New Testament studies for 25 years at the Interdenominational Theological Center, Howard University School of Divinity and Hartford Seminary. Before that, Hoyt served as pastor of several CME congregations in North Carolina and New York.

He has a B.A. from Lane College, Jackson, Tenn.; an M.Div. from Phillips School of Theology of the Interdenominational Theological Center, Atlanta, Ga.; an S.T.M. from the Union Theological Seminary, New York; and a Ph.D. from Duke University.

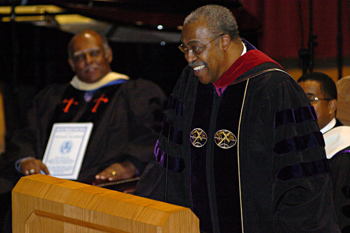

Hoyt visited Duke Divinity School to deliver the 2012 Martin Luther King Jr. Lecture and spoke with Faith & Leadership. The following is an edited transcript.

Q: You’ve been deeply involved in the ecumenical movement. Why is ecumenism important?

People call me an ecumenical fanatic, and I don’t think they quite understand what that means. I am fanatical about it. I define a fanatic as a person who will not change one’s mind and will not change the subject. In both instances, that’s been my case.

I won’t change the subject about what it means to have relationships with other denominations, other people and humanity. It’s not just churches. Ecumenism is how you deal with human beings of all persuasions, which means that one has to be open to people who don’t have the same ideas. That helps me navigate through various phases of life, to be open to receive what others have to give.

Q: What is the value of ecumenism from the vantage point of the CME?

From the beginning of the CME Church in 1870, we have been involved in ecumenism. The African Methodist Episcopal Church and the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church started before we did, but all of them have their roots in the United Methodist Church. We came out of the Methodist [Episcopal] Church South. But we have never alienated ourselves from the larger church. We have always been ecumenical.

We’ve always had relationships with the National Council of Churches and the World Council of Churches.

When the Consultation on Church Union [COCU] encouraged people to go into parishes and have meetings to plan programs for the future, to work together across race and culture, the churches turned that down. That was disappointing to me, because I thought that’s what we were together for, to work together.

The CME Church and the black churches have always seen COCU -- and now CUIC -- as an organization that held out hope for the races to get together and to see if they could not work together.

[The Consultation on Church Union was an effort begun in 1962 to merge a number of Christian denominations. When the denominations rejected merger in 1969, the group’s focus shifted to “intercommunion.” COCU was dissolved in 2002, succeeded immediately by Churches Uniting in Christ (CUIC).]

Q: What prompted you to get involved in COCU?

I was a student at Lane College in Jackson, Tenn., and a woman there was very instrumental in putting me into the Student Christian Movement. As president of the campus Student Christian Movement, I went to Oberlin and other places and met people of different races from all over the world. That introduced me to a paradigm that I had not been used to.

I was brought up in Alabama, where you had segregation, colored fountains, and I couldn’t go into the restaurant and get a cup of coffee. But when I got to college, this lady took me to Oberlin, Ohio, to Nashville, Tenn., to other integrated communities, where I started meeting people of various races and cultures. That gave me a sense that the world is larger than what I had been used to.

Q: When was that?

1958, 1960.

Q: That was really quite a period.

It was. Martin Luther King was going through the nation breaking down some barriers. And I was being introduced to ecumenical work because of good teachers and role models like Martin Luther King.

My father was not quite as out-there with integrating, but he was always instilling in me a sense of “somebody-ness” -- that you are somebody special, that you can do what you need to do to make an impact. But when he saw Dr. King going around, he said, “Why don’t that man stop going and stirring up stuff?”

A lot of black people did not have the notion that Martin King was a hero at that time. They saw him as stirring up things. King was one of my heroes, and I think that what he did was to stand up for what he thought was true and right and good for the people.

Q: Change can be a frightening thing.

Well, my father wanted things to change, but he didn’t quite see how they would change. When we’d get ready to go on trips, he would fry some chicken and put it in a basket or bag, knowing we couldn’t stop down the highway, because we couldn’t go in those restaurants.

People fighting against oppression sometimes end up oppressing, because they don’t know how to have another value system.

Q: Tell us about your work with the National Council of Churches. You were president and were involved in social justice work around the Immokalee farm workers.

I went down on the farm to encourage some of the workers to say that they needed better wages, and also some remuneration for insurance and all that. We worked on that. It had already started when I came on as president, but I tried to give it some high visibility, which we did.

Q: Were you criticized internally for that?

No. I didn’t get any criticism from my people so much as I got encouragement.

Martin Luther King faced criticism, however, when he started going into the subject of Vietnam and extending the civil rights movement into Vietnam. He said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” which, of course, it is.

We can’t be selfish about helping other people, be they black, white, Mexican, Indian or whatever. Where there’s injustice, we have an obligation to speak out and to bring what powers we have to bear upon those instances.

Q: You’ve long advocated for adequate pay and quality theological education for pastors. How much improvement have you seen on these issues in your denomination or others?

It’s still a problem. Most of our preachers are tent makers. They have their own jobs and that creates a problem. We don’t have enough people to take these positions without some flexibility.

There are some good churches that pay good money. But I try to get the preachers not to come in talking about “What is the package?” before you help develop this package.

You’ve got to become a pastor to the people, and that’s what I tell them all the time. I can put you there, but I can’t keep you there. So they’ve got to become what people need to have in their communities.

In terms of pay and the salaries, we still have a problem. We don’t have a lot of them making good salaries. We don’t have a lot of them with health care. They’re usually on their wives’ health plans, and that’s not only the black churches; that’s white churches, too.

It’s a task, but it also is a challenge that we don’t give up on. We started off one time trying to have a minimum salary, but that didn’t go far. We got in the books that a minimum salary is $16,000, but even that is not what some of our preachers are making.

Q: Do you see any solutions?

Over the long haul, I do, but not right now. Steward boards propose the salaries, and when they’re not making much in their own jobs, that carries over into their proposals for the pastor.

Over the long haul, the solution is that salaries of the people in the community are enhanced. They say a rising tide lifts all boats, and I think that’s true in the church, as well as in the larger society.

Q: You’re both a scholar and a church leader. How do those roles relate to each other?

Somebody told me, “You’ve got to give me an article to go into my book before you become bishop, because we won’t hear from you anymore after you get elected.”

I said, “Well, that’s the stereotype they have of bishops -- that they don’t have time to write.”

I found that to be true. You start concentrating, and all of a sudden you’ve got somebody calling you over here and over there, and you find you can’t have any consistent time to write.

I’ve done some writing since I’ve been on the bench. I have a book on the Gospel of Luke, a 52-week Bible study. I wrote a background on Romans for a commentary called “True to Our Native Land” by Fortress Press. I helped to do some things for the “Jubilee Bible.” I’ve worked with inclusive lectionary readings.

I find that you have to find your niche as a scholar and your niche as a bishop and try to put those together in a way that will help people in their local churches.

I feel like I’ve done my best to bridge the gap between scholarship and what it means to deal with biblical interpretation. I made that attempt, and hopefully was successful in some of that.

Q: What issues do you see facing your denomination and ecumenism in the future?

What affects us now is hermeneutics. That is, how to translate the gospel in a way that would help people see how it affects all of life, not just segments. There are those who contend that the biblical text ought to stay out of politics, and they can’t. As long as you deal with humanity, you’ve got to be in politics, because where one or two are gathered, there’s politics. And where one or two are gathered, God is in the midst. They go together.

Right now we are confronting human sexuality in our churches -- the relationship between sex and religion, and how you deal with that. We have those issues being raised, but we haven’t begun to deal with how to navigate them. We’re saying, “I’m against it. I’m against it.”

Well, I’m against what? Are you against human beings? Are you against sexual activity between male and female, or against male and male, or against female and female? Lots of churches are breaking up over just those little issues. But it’s a real problem.

Q: Are these issues being raised in the CME?

Yes. One of our retired bishops, Bishop [Othal] Lakey, has just written a book on homosexuality and given the history of it in the church. It’s getting a lot of publicity in our church. But we don’t know whether it’s a health issue, or whether it’s a choice that people make, or something that the biblical text can talk about. Is it against the biblical text? That’s a question that some people are sure they know the answer to, but others say they don’t know.

Q: How about you? Do you feel like you know?

I don’t. I have to admit that there are things that I don’t quite understand. But what I come down to on the matter is that these are human beings and they have to be treated as human beings, and that the church has to be pastoral in whatever they undertake to do. They can’t be judgmental, but they have to be pastoral. What that entails is treating people with love and respect and humanness.

We need to be open to receive what others have to give. I haven’t quite gotten all the answers, but I’m there to try to receive what people have to give. That’s what I’m trying to do.