Selma Ait-Bella hadn’t officially started her freshman year at Virginia Commonwealth University when she first walked through the doors of the Pace Center in the heart of the school’s 200-acre Richmond, Virginia, campus.

A family friend and VCU upperclassman had invited Ait-Bella to the summer 2021 gathering, suggesting that she might enjoy some of the social activities offered at Pace. Ait-Bella, who knew almost nothing about the center for campus and community ministries, expected a casual meet-and-greet. The gathering was instead a long-range planning meeting, where students, professors and pastors from throughout Richmond were hammering out goals for the ministry, which has ties to the United Methodist Church but operates as an interfaith space.

Even more surprising, said Ait-Bella, now a 19-year-old sophomore majoring in sociology, was how interested they all were in what she had to say.

“They were asking things like, ‘What do students want? What are the goals of the students coming here?’ And I’m not one for awkward silences, so when they asked a question, I’d raise my hand,” she said.

Pace Center among 2022 award winners

Leadership Education at Duke Divinity recognizes institutions that act creatively in the face of challenges while remaining faithful to their mission and convictions. Winners receive $10,000 to continue their work.

Having spent the better part of her final 18 months of high school in quasi lockdown because of the pandemic, she was looking for a place to learn from others, connect and be heard. As she spoke to a roomful of strangers, she noticed how the Rev. Katie Gooch, Pace’s director, made regular eye contact, encouraging her to expand on her thoughts. Ait-Bella, a Muslim, said she’d initially wondered whether it was OK for her to be in a Christian space, but her hesitation quickly evaporated.

“I was met with all these smiling faces and all this encouragement. I learned so much about what Pace was in that space. It helped me build agency really quickly,” said Ait-Bella, who now sits on Pace’s board and participates in its servant-leader fellowship program.

Where in your community can people learn, connect and feel heard?

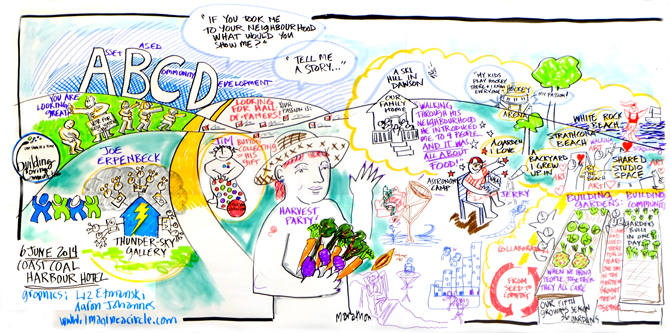

Listening to the hopes and dreams of students and then empowering them to achieve their goals are top priorities for Gooch, her staff and the community partners who volunteer at Pace. The organization relies on a strategy called asset-based community development — or ABCD for short — that emphasizes uncovering a community’s gifts rather than focusing on its deficits.

The method, pioneered by professors John L. McKnight and John “Jody” P. Kretzmann, who co-founded DePaul University’s ABCD Institute, takes what practitioners often refer to as a “glass-half-full approach” to community revitalization. Residents start by identifying their strengths, then build nurturing relationships with others who share those gifts before engaging in community-led change, said Wendy McCaig, a Richmond-based ABCD coach who has helped Pace adopt the practice.

“It’s not about discovering the needs of a community and fixing it. It’s helping people find what they most care about and leaning into that,” said McCaig. “When you see somebody come alive because they’ve found something connected to their calling, that’s the hook.”

Gooch said the process at Pace starts with listening. She often asks students, “If you could do anything at VCU to help build community, what would you do?” The answers frequently inspire programming, which is almost entirely student-led, ranging from weekly dog walks and multicultural meals to open mic nights and community service projects — all in the name of creating a welcoming, affirming community.

How do you find out what people most care about in your community?

Students are encouraged to reflect on their own gifts and recognize the gifts in others, and not just at Pace. The goal is for them to model this approach in their classrooms, at their jobs and in organizations. Gooch said students often refer to the parable of the tiny mustard seed that grows into a towering plant.

“We’re not baptizing 100 students every semester. We’re just planting seeds,” said Gooch, an ordained UMC pastor. “For some people, that seed is, ‘I walked into a building that looked like a church and didn’t have a terrible experience. Maybe I take that feeling with me, not into a church, but to my work or my living space.’”

Gooch estimates that about 1,000 students come through Pace’s doors each year, the majority of them alone. If there’s an event happening at Pace, it’s almost guaranteed to be student-led, with just a few rules set by the staff: Every VCU student must be invited — a task usually accomplished by posting the activity on RamsConnect, the university’s student organization calendar. Everyone must be greeted warmly and affirmed. And no one sits alone.

“When you’re a first-year, you feel like everybody but you has a community already,” said Tobi Ojo, an 18-year-old freshman from Chesapeake, Virginia, who comes regularly to Pace’s Stories & Lunch on Wednesdays. “But when I walked in here, everybody was really warm, and they quickly knew my name.”

Dazia Williams, a 21-year-old senior from Philadelphia, noticed something similar when she first visited Pace last year. Though pandemic restrictions had eased, her roommate hadn’t returned to campus, and Williams was craving contact.

“I was so lonely,” said Williams, now a Wednesday lunch regular. “Everybody tells you when you go to college to make connections, but no one tells you how to make connections. But here, the conversations are just natural. Pace really helped me be able to hold conversations again.”

‘See the richness and not the brokenness’

There weren’t many conversations happening at Pace when Gooch arrived in 2016 after serving as an executive pastor at nearby Reveille United Methodist Church. The Pace building itself, erected in the late 1960s after the original church there burned down, was in disrepair. The congregation of what was known as Pace Memorial United Methodist Church had disbanded around 2000 as members moved to the suburbs and VCU’s campus expanded into the surrounding neighborhood. For the next 15 years or so, the building, owned by the Wesley Foundation of the Virginia Annual Conference of the United Methodist Church, was designated as a space for a campus ministry, but “it never hit its stride or found its way,” Gooch said.

That meant she could start with a blank slate, with no programs or students who needed keeping up with. At a friend’s suggestion, she contacted McCaig, who encouraged Gooch to conduct informal “listening surveys,” asking students about their hopes and dreams and what they wanted out of their VCU experience. Pastors at several local churches also connected Gooch with some VCU students who went through the listening surveys with their friends and classmates.

It would have been easy, McCaig said, to be distracted by some areas of high need. Many students are low-income and facing food insecurity. Roughly 30% of VCU’s 22,000 undergrads will be the first in their families to graduate from a university. But the first step in ABCD is community listening — and the students Gooch and her team connected with weren’t focused on any of those things.

“The big ‘aha!’ was when they did the listening project and heard the heartbeat of the students. It wasn’t, ‘I need more food in my fridge.’ It was, ‘I want to connect with other people,’” McCaig said. “That’s when they started to see the richness and not the brokenness.”

Gooch said students expressed a deep need for togetherness and a desire to celebrate the university’s diversity. Many also identified cooking among their gifts or hobbies. One of the first activities the students organized at Pace was a multicultural Thanksgiving celebration.

Gooch laughs when she thinks about it now. For years, adults ran all the events at Pace, making sure they were well-advertised and highly organized, and a handful of people would show up. When the students ran the show that fall, there wasn’t much advance notice, the event started late, and the rice was burned — but no fewer than 70 students showed up, and they had a great time.

“It was like, ‘Whoa, what is happening here?’” Gooch said.

Part of resurrecting Pace as a welcoming space meant the students needed to feel free to make mistakes and learn from them, she said. While the staff keeps the lights on and sets aside programming money, it’s the students at Pace who take the wheel when it comes to steering the organization’s direction.

What would happen if students ran your programs? What would be different?

Many of the student leaders at Pace participate in a semester-long fellowship designed to foster personal and professional growth. They’re encouraged to go outside Pace’s walls and strike up meaningful conversations with other students, often starting with a question similar to the one Gooch posed years ago: If you could do anything to build more community at VCU, what would that look like for you?

To measure the level of a respondent’s passion, there’s usually a follow-up question: If we found others who were interested in that same activity, would you want to join them? If the answer is “yes,” three more questions usually follow:

1. What are the gifts of your hands? These include skills you might like to share, covering everything from juggling to needlework (there’s a Strings & Things crochet and knitting group that meets weekly).

2. What are the gifts of your head? These include topics you know something about and might enjoy discussing with others.

3. What are the gifts of your heart? These are issues you’re passionate about, like the environment, social justice or animals.

Fellows are taught to recognize when respondents’ faces light up, a sign they’re sharing something they care about. At weekly meetings, fellows discuss what interests they’ve uncovered among their classmates, and if there’s enough passion around a particular topic or activity, they invite those respondents to come and plan something at Pace.

Not every conversation results in an event at Pace, Ait-Bella said, but each generates a connection.

“I think it comes down to being directly asked and listened to,” she said. “Some people are just waiting to be asked for an opportunity to lead something. And when you’re asked for your input and you see it in action, you want to come back. You want to see your vision in play.”

VCU boasts about 500 student organizations, and competition for on-campus event spaces is at a premium. Student leaders at Pace have collaborated with other clubs to host a variety of cultural events and community conversations — all without the bookkeeping requirements and red tape that the university sometimes requires, Gooch said.

The Pace staff provides opportunities for reflection and guiding questions as students organize mixers, jam sessions and mindfulness activities. But the students own the logistics and establish measures of success.

Russ Kerr, Pace’s student development and engagement coordinator and an ordained Presbyterian minister, said students are primarily focused on forging relationships and building a deep well of ownership, so that no program is dependent upon any one person. Questions they often ask themselves: How many gifts did I discover in someone else today? How many gifts did others use in today’s program? Did participants feel free to take initiative today without holding back? Did I make any connections outside the walls of Pace?

“The measure of success is somewhat intangible here, but it’s all about community building, sharing God’s love and making people feel valued,” said Jean Linnell, the associate director at Pace and a VCU grad. “Did the rice get burned? Yes. But did somebody make a friend? Are they going to come back because they felt so welcomed here? That’s the success we’re looking for.”

Connecting and leading

On a recent Wednesday afternoon, Pace hummed as students prepared a half-dozen long tables for a lunch crowd. While they arranged place settings, volunteers from nearby St. Paul’s Episcopal Church placed bowls of salsa, corn relish, guacamole and other fixings along a buffet table for Stories & Lunch, the weekly gathering where students enjoy a free meal and conversation.

Elijah Bustamante is today’s emcee, and once diners have filled their plates, the sophomore from Chesterfield, Virginia, introduces an icebreaker, encouraging the roughly 40 guests to share with their tablemates their names, preferred pronouns and costume plans for Halloween. It’s one of the only times the students take out their cellphones, sharing images of costumes depicting cowgirls, fairies and anime characters.

Moments later, Bustamante is out of his seat again.

“I’m gonna cause some chaos right now,” he says, giving the students five minutes to find all the fun-size candy he’s hidden around the building. Taped to each pack of KitKat, Twizzlers and M&M’s is a conversation prompt — What’s something almost no one knows about you? What’s something you’d like to learn more about? Back at their tables, guests respond to those questions. “I was born in Hawaii,” offers one. “I’d like to learn more about spirituality,” says another. “I’d like to learn more about myself,” responds a third, prompting nods of affirmation.

What are the intangible markers of success in your community?

When he first began helping with Wednesday lunches last year, 15 to 20 people generally gathered around a conference table for the meal, Bustamante said, and one or two leaders handled most of the logistics. But during reflection meetings, participants asked for more intimacy, so they replaced the one large table with a half-dozen smaller ones. Bustamante also recruited a team of volunteers to handle setup and cleanup and suggest weekly conversation topics. The lunch crowds are larger these days, he said, but more importantly, more students feel empowered to share their gifts.

“Before, we looked at numbers — that’s easy data to look at. But over time, we started to notice the growth within people, the number of times people returned and the relationships,” said Bustamante, 20, who is a fellow this semester.

Bustamante said that at Pace he’s learned how to “command a room.” He uses that skill regularly as the social chair for FACT, Filipino Americans Coming Together, a large organization at VCU.

“This space provides such a safe environment for me to make mistakes and to be myself,” he said. “The Pace Center has helped me fully know that I had that leadership within me, and I’ve gained this skill of creating and maintaining relationships. I have created so many new relationships since I joined Pace, and we all hang out together outside of Pace.”

How do you cultivate an environment in which people can make mistakes and be themselves?

Bustamante said he had no idea Pace was a campus ministry when he first accompanied a friend for lunch. The brick building features some stained-glass windows and a large wooden cross on the sanctuary wall, but its religious affiliation is pretty subtle. Pace offers a communion service on Wednesday mornings and a Scripture & Conversation gathering on Friday afternoons, but most activities are secular.

Pace partners with an ecumenical mix of nearby churches that are LGBTQ-affirming and whose members often provide meals and supply kits for students, serve as mentors to those exploring career options, and donate to Pace’s budget. A grant from the Board of Higher Education and Campus Ministries (BHECM) of the Virginia Conference of the United Methodist Church covers Gooch’s salary and benefits, but Pace relies largely on donations for the rest of its $215,000 yearly expenses.

Second Presbyterian Church treats its relationship with Pace like a mission, incorporating funding for the center into its annual budget, said the Rev. Alex Evans, the church’s lead pastor. Collaborating with Pace gives the church, which is about a mile away, an on-campus presence, and Second Presbyterian’s pastor for campus ministry and urban engagement, the Rev. Kelley Connelly, is posted there most of the time. The students who come to Pace care a lot less about the organization’s religious affiliation than they do about how they’re treated, Evans said.

“They don’t care if it’s Presbyterian, Methodist or Episcopal,” he said. “They care if it’s welcoming, nurturing and encouraging them to do better, and that sounds like Jesus.”

Those partnerships go both ways. Many of the students at Pace volunteer with the churches’ missions and even teach church volunteers about the ABCD method. Williams, the senior from Philly, was volunteering with Second Presbyterian, handing out bag lunches, when she heard about Pace. As a woman of color on a predominantly white campus, she was seeking an inclusive space, she said. She’d noticed how some of her friends, particularly in the LGBTQ community, had avoided churchlike settings, “because they feel parts of them, they can’t bring there,” said Williams, who was raised Baptist.

How do you create a space that “sounds like Jesus”?

“The first day I came, it didn’t give me that typical church environment. It felt like a student center, and that’s why I came back,” she said. “You know how people sometimes ask you how your day is going, but you can tell they don’t really care? At Pace, that doesn’t happen. You can talk to everyone. People don’t understand how listening can be so helpful sometimes.”

Williams said she tries to model that behavior at her on-campus job and in the organizations she’s joined. Connelly said that’s exactly what Pace is trying to promote.

“The growth doesn’t have to be monumental,” she said. “The hope is, they really just become confident in who they are, that they feel loved, that they feel seen and feel led to share that love with others.”

Questions to consider

- Where in your community can people learn, connect and feel heard?

- How do you find out what people most care about in your community?

- What would happen if students ran your programs? What would be different?

- What are the intangible markers of success in your community?

- How do you cultivate an environment in which people can make mistakes and be themselves?

- How do you create a space that “sounds like Jesus”?