The recent murders at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, are a small part of a larger story of the United States and its continued reliance on violence to try to bring about peace and security, said the Rev. William H. Lamar IV, pastor of Metropolitan AME Church in Washington, D.C.

Dylann Roof, Lamar said, is just the latest in “a long line of persons who have believed that violence against black people will bring about the peace and power that they seek.”

In the aftermath of the Charleston shootings, church leaders must begin to have real conversations about the truth of the nation’s history, he said.

“How do we get out of this myth of redemptive violence?” Lamar said. “We have to tell the truth about American history.”

Those conversations aren’t about “blaming and being stuck,” he said.

“You have to do it as a means of purging this lie that there has been unchecked freedom, liberty and opportunity in America,” he said.

Before becoming pastor at Metropolitan AME Church last year, Lamar served as pastor at Turner Memorial AME Church in Maryland and three churches in Florida. He is a former managing director at Leadership Education at Duke Divinity. Lamar is a graduate of Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University and Duke Divinity School.

Before becoming pastor at Metropolitan AME Church last year, Lamar served as pastor at Turner Memorial AME Church in Maryland and three churches in Florida. He is a former managing director at Leadership Education at Duke Divinity. Lamar is a graduate of Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University and Duke Divinity School.

He spoke recently with Faith & Leadership about the Charleston shooting and the challenges it poses for the church. The following is an edited transcript.

Q: What has the past week been like for you and your congregation?

For me and the people that I’ve been blessed to serve for the past year, it is a required discipline not to use the language that American culture keeps using about, “This is a surprise. Oh, my God! How does this happen?”

As if this is something new.

James Baldwin has a phrase that I love: “History, I contend, is the present.” This, to me, is the same as the 16th Street bombings. It’s the same as Emmett Till. It’s the same as the destruction of Rosewood in Florida, Black Wall Street in Tulsa.

There is an unbroken assault on black bodies in America by certain segments of the population who don’t even realize that they’re animated by a myth of white supremacy and redemptive violence. They are not even cognizant that their political and theological ideologies come from stories that in and of themselves are not only untrue but also trap everybody in this nation and many people in the world in a story that will continually have the world convulsing in pain and violence until we do something different.

Q: Speak some to that. You preached Sunday about the myth of redemptive violence.

It comes from Walter Wink’s theological work. He looked at creation myths and how the story just plays itself over and over again -- that when good guys kill the bad guys, when violence is used, then everything is tranquil, everything is OK.

If we move to a different narrative from this myth of redemptive violence, then there’s a chance for all of America to be free because all of us are trapped in this narrative.

But what happens is that violence in and of itself keeps reproducing. When I look at Dylann Roof, I see him standing in a long line of persons who have believed that violence against black people will bring about the peace and power that they seek. But what it does is it continues to destabilize.

You can look at his story in microcosm but you can look at the larger story of the United States -- its conquest -- and America’s continued reliance on violence to try to bring about peace and security.

It never will happen. People may say it’s dreamy foreign policy, but war is not going to bring peace, whether that’s an individual with a gun in a church or whether that’s a nation with this mighty military arsenal. It’s not going to happen, so we’re trapped in that logic, and we’ve got to get out of it.

Look at people who have been successful in bringing about social change -- King, Gandhi. They stared down that myth. You can say the same of Jesus Christ. He stared down that myth and offered a different narrative reality.

It will not be painless. It will cost blood and people’s lives but it’s necessary if we’re going to do something different. It’s sickening to think that this country has been unwilling to have a conversation.

I was watching [South Carolina Gov.] Nikki Haley on the news about bringing the Confederate flag down in South Carolina. Shortly after she talked about that, she went directly back to using American mythic language: “July 4th is just around the corner. Soon we will once again celebrate . . . our freedoms.”

We will not stay long enough in the pain because staying in the pain and dealing with the truth of history will implicate power -- those who have power, and how their ancestors gained the power, and it will reveal what they’ve done to keep the power.

Q: You’re the pastor of a historic AME church. What is the impact for you and your congregation that this happened in an AME Church, especially given the denomination’s history?

The AME Church has to recover its tremendous, glorious history. I spoke recently with the former historian of our denomination, and he said that our ministry and our theology has always been a ministry and theology of risk.

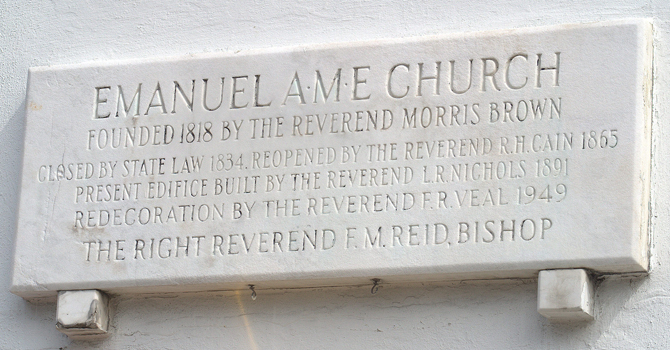

Go back to Mother Emanuel’s history. Denmark Vesey’s slave insurrection was planned in a Methodist class meeting at Emanuel Church. Think about that -- a slave insurrection to overthrow the evil and brutal slave powers in Charleston.

Someone told me recently about how beautiful Charleston is. Well, if you look beneath the surface of the beauty, there’s the misery of our ancestors. Charleston was the major slave port on the East Coast. Roof knew that part of the history. What he probably did not know was that insurrection was hatched in a class meeting at Emanuel Church.

Morris Brown, the pastor at that time, had to leave, and South Carolina made it illegal for the churches to gather because they knew that if black people could meet, they would seek insurrection and their own freedom.

So this pastor has to run from Charleston to Philadelphia, where the founder of the AME Church, Richard Allen, was. And Allen accepted Morris Brown into his home, made him his assistant and then upon Richard Allen’s death, Morris Brown becomes the second bishop of our church.

I do have hope that the God that I serve is a God who wants to bring justice for all people, and so I take comfort in that. But what I also know is that God is depending on us to fight that fight. You don’t pray and expect these things to descend from the sky.

We have to recover that our theology has always been one of risk, that we have always fought for freedom, and that our leaders were willing to risk their lives, their families’ lives, their reputation and their wealth.

We have to return to that risk-taking ministry. When black people in America were clear that the AME church loved them, they loved the AME church.

We grew and grew and grew, and we began to believe that a few civil rights’ victories and a few token positions meant that we were free. When we stopped fighting, stopped advocating, stopped harboring those who were looking for freedom and justice, then we began to lose some of the power we had in the black community.

If we move to a different narrative from this myth of redemptive violence, then there’s a chance for all of America to be free because all of us are trapped in this narrative. Until there is a new narrative of who we are and what we do, this will continue to happen.

One of the things happening now is that many white people are convulsing in fear because of demographic changes in America, and that will continue to fund the craziness of Dylann Roof and others.

Q: What’s your advice and message for church leaders?

I would hope that church leaders would take this opportunity to have real conversations about the truth of the nation’s history.

How do we get out of this myth of redemptive violence? We have to tell the truth about American history.

We have to tell the truth of conquests. We have to tell the truth of human misery. You’ve got the Washington Monument and the Jefferson Memorial here in the city I serve. You’ve got to tell the truth about those people and how they insisted on a way of being in this country, a way of subduing it and growing it economically that resulted in generations of human misery.

We can’t do it as a means of just blaming and being stuck. You have to do it as a means of purging this lie that there has been unchecked freedom, liberty and opportunity in America, a lie that we continue to tell at every political speech, at every rally.

That has to be supplanted by a truth of what has happened in this land and that, possibly, in reading and knowing and telling the story truthfully, we can gather up the crumbs and move forward in a way that looks more just.

If we keep papering over the misery that made America what it is with flags and patriotic speeches, you continue to hide that truth, and after a while that truth is going to fester and boil up to the surface like it continues to do week after week and month after month.

Q: What’s your message for white Christians, for white mainline denominations? What do they need to be doing?

The white mainline church has to admit that in its founding in America, in its perpetuation of power, its theology has been funded by white supremacists. You can call it something different but that’s what has funded it for multiple years.

They talk about the black church being political. Well the white church has always been political, and its politics have been to maintain white control of the economic and political spaces and theological space. The white church has to admit that its theology is rooted in notions of white supremacy. You might not be able to find and document “We believe in white supremacy,” but if you looked at the language and how the institutions were built, that’s one of the bedrocks.

It can seem overly simplistic but just as black people have to reckon daily with America’s racial reality, white Christians are going to have to pick up that cross and bear it and deal with the privilege that they have and deal with the fact that their mothers and fathers used the church to consolidate white power and make it larger.

There are some serious internal conversations that the black church has to have and that the white churches have to have. I know it’s a difficult burden for white Christians and they may not want to stay in the conversation. But to be honest, I have very little patience with white Christians not wanting to stay in the conversation. We have to stay in the conversation. We have no choice.

Q: What’s the particular risk, the particular action, that the black church has to take? What’s the particular risk white churches have to take?

Black churches sometimes have confused becoming proper, middle-class black people with following Jesus. We have to stand in solidarity with our brothers and sisters who experience the most painful realities of what it means to be black in America. We have to understand that the church can’t just become a social club funded by notions of Negro respectability.

We’ve got to take risks. That’s what we have to do internally.

For the white church, just like I often get tired of white people speaking for black people, I don’t want to start speaking for white people. But based on my limited understanding of white folks, I think that white folks have a tremendous burden in America that they have to begin to pick up.

White people have to understand the privilege that comes with whiteness and where that privilege comes from and the human misery upon which it is built. They have to understand that politics and theology had to be constructed to make that so and those politics have to be dismantled and we cannot be fooled or lulled to sleep by situations like bringing down the [Confederate] flag.

I’m all for bringing down the flag, but that does not bring justice. Bringing down the flag should begin a conversation. There’s much more that needs to be done. Bringing down the flag is not insignificant but it’s not going to free anybody.

Racism is permanent. For anyone from a theological perspective to say that racism will end is like saying that sin will end. Sin will never end. Racism will never end.

Black people need to understand that this fight is everlasting. My grandfather fought it in his day and we have to fight it in ours. There will be no point, in my opinion, where we can say this is over.

Q: Do you see signs of hope, and if so, where?

You’ve got optimism, and you’ve got hope. Optimism is anthropological. It depends on what human beings do. I don’t have much optimism about what’s going to happen. I think that human beings can do better, but I don’t often think we are willing to do what’s necessary.

But I do have hope that the God that I serve is a God who wants to bring justice for all people, and so I take comfort in that. But what I also know is that God is depending on us to fight that fight. You don’t pray and expect these things to descend from the sky.

You pray. You strategize. You organize. God will animate your efforts, but it’s not just going to happen.

I’m not hopeless but I don’t want to be lulled to sleep by symbols that are meaningful but do not mean that justice has come and that we have truth and reconciliation in America.

I see hope whenever groups of people sit down and stay in tough conversations. I see hope when people really understand that what we need in America is people with power willing to give that power up.

When I’m in the church, I’m hopeful when I see people not afraid. They’re still going to come to church. As a matter of fact, we had more people in the church on Sunday than normal so there may be something that the blood of the martyrs will indeed become the seed of the church’s growth. I’ve seen signs of hope when white strangers have walked in off the street and given us flowers and say, “We’re praying for you.” But it’s not enough.

So, I’m not hopeless but I just refuse to be lulled to sleep by the language that we always speak in America about freedom and justice for me, when the Scripture says everybody cries, “’Peace, peace,’ when there is no peace.”

I just can’t square it.