It took Anne Blue Wills 10 years to finish her biography of Ruth Bell Graham. There are good reasons for that.

Wills was otherwise fully engaged as a wife, mother and professor of religious studies at Davidson College in North Carolina, where she was named chair of religious studies.

But mostly, she was devoted to capturing the complicated legacy of Billy Graham’s wife. Her book, “An Odd Cross to Bear: A Biography of Ruth Bell Graham,” offers a sympathetic yet objective look at an extraordinary woman.

Ruth was content to live in her husband’s shadow, caring for their five children while he circled the globe in praise of Jesus. But keeping the kids in line — she once locked a misbehaving Franklin Graham in the trunk of her car — wasn’t all she accomplished.

She had grown up in China, the child of American medical missionaries for the Southern Presbyterian Church. Ruth was a writer and speaker and her husband’s most trusted adviser. She oversaw the construction of the log cabin in which the Grahams lived (and Billy died) in Montreat, North Carolina.

She was, Wills says, maternal, stubborn and a practical joker. She was brave; she lived with chronic pain starting in 1974, when she fell setting up a zip line for her grandchildren. She died June 14, 2007, at 87.

Ruth did not identify herself as a feminist; she insisted that her liberation grew from God’s promises fulfilled through Jesus. On a 1979 broadcast of The Phil Donahue Show, she said she was “liberated from having to earn a living.”

Yet Wills argues that Ruth lived an independent life even if she rejected the feminist label.

Wills is a native of Greenville, South Carolina. After graduating from Davidson, she earned a master of divinity degree from Yale Divinity School and a Ph.D. in American church history from Duke University.

“An Odd Cross to Bear” is Wills’ first book, and was honored by Christianity Today's 2023 Book Awards as the year's best work in history and biography category. She spoke with Faith & Leadership contributor Ken Garfield about Ruth Bell Graham’s life and influence. The following is an edited transcript.

Ken Garfield: Where does the title of the book, “An Odd Cross to Bear,” come from?

Anne Blue Wills: Ruth was always fielding questions about what it’s like to be married to Billy Graham. Ruth said, “It’s an odd kind of cross to bear.”

What she came to understand is that it was a vocation for her to be married to Bill (that’s what she called him), to share the work he was doing and keep him focused on evangelism. It was something she believed in doing and knew that she was intended to do, purposed to do, but it was hard.

KG: What do you want readers to take from this book regarding Ruth Bell Graham’s life and legacy?

ABW: She never wanted to be dowdy or unapproachable. The first time that Billy went to lead a crusade in London, in 1954, the organization was not sure they were going to draw a crowd. Billy wanted her to take off her makeup. They wanted all the women in the party to take their makeup off. She pushed back and said, “What credit does it do to Jesus for me to be dowdy?”

She was naturally beautiful. She enjoyed nice clothes. She enjoyed shopping, apparently. She had a kind of cool, Southern style to her. My students’ generation, they think of her as a stuffy, dowdy churchwoman.

Ruth didn’t look that way. She didn’t act that way. She wanted to be up to date, and she wanted to keep Billy up to date. That’s one thing I would like readers to know about her life.

As far as her legacy goes, it’s a little trickier and maybe not as positive.

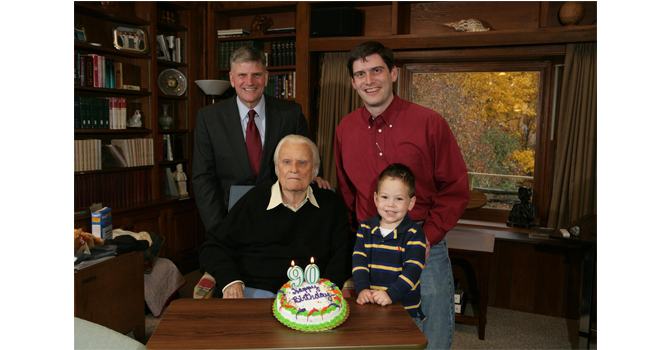

Franklin [Graham] and Anne [Graham Lotz] are the two Graham children who have the most public profiles. [Franklin runs the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association; Anne is an evangelist and author.]

If we consider the work that each of them does as part of Ruth’s legacy, there’s a lot of Ruth in both of them. I think it’s more in terms of temperament and the willingness to call out things, maybe controversially.

KG: Ruth was strong. She was independent. But she was a stay-at-home mom who deferred to her husband. How do you situate her in terms of feminism?

ABW: For women of faith who are shy about identifying themselves as feminists, she offers a way to complicate or maybe uncomplicate the ways we think about feminism.

For example, I identify myself as a feminist because I believe that women are fully human and patriarchy hurts everybody. Patriarchy constrains everybody.

I think about the ways Ruth was constrained. She married Billy instead of maybe becoming a single female missionary. But that was a decision she made because she loved him and was able to sort through her faith commitments in such a way that it made sense to her to marry him, to go that route rather than dedicate herself as a missionary.

KG: Is there a moment in Ruth’s life that touched you the most, a moment or chapter in her life that spoke to you personally?

ABW: One of those moments is meeting Billy in 1940. They were so young when they met. Oh my gosh, they were [early 20s]. He was handsome. She was so beautiful. The magnetism that had to exist between the two of them!

That’s one thing that humanizes them for me and helps me time-travel back to the late 1930s and early ’40s with them on a college campus. They’re very glamorous to classmates at Wheaton [College]. Everybody on campus loves them.

They just were kind of human to me as young people.

At the other end, I have a lot of pathos around her being buried in Charlotte, North Carolina. In some ways, it makes me really sad for her, that this brilliant, loving woman becomes reincorporated as a pawn.

[The Washington Post broke the story of the family squabble over Ruth wanting to be buried in the North Carolina mountains and their son Franklin wanting her and Billy to be buried at the Billy Graham Library in Charlotte.]

Is that too strong? It makes me a little angry. On the other hand, she doesn’t have to worry about it anymore. In my understanding of the world, she and Billy are together again, and that’s all that matters.

[Such was the contrast in how they handled illness that the family would joke that Billy’s tombstone would say “I told you so” and Ruth’s would say “Never felt better.” Her actual tombstone declares “End of Construction — Thank you for your patience,” words she had read on a road sign.]

KG: Is there a moment in her life that you studied that you wish you could have told her, “Don’t do that”?

ABW: The thing that happened when Gerald Ford was in Charlotte in 1975 [when the president came to speak at a bicentennial observance in Graham’s hometown].

KG: I knew you were going to say that.

ABW: The Charlotte Observer’s stories are super, because you can just feel the heat in the sun. People are uncomfortable. There sits Ruth in the front row, and this guy has his sign. It says “Eat the rich” [protesting the event’s mix of religion, business and politics]. You’ve got Billy Graham there, for Pete’s sake.

Ruth takes the sign and puts it under her feet [so the protester can’t retrieve it]. Just the physical comedy aspect of it.

He accuses her of pushing him or somehow putting her hand on him, so he brings assault charges. She shows up perky as a petunia in court with three attorneys. The judge dismisses the charges. She said beforehand she’s not copping a plea.

KG: Don’t you think that story speaks to her spirit?

ABW: Oh yeah. Stubborn. Maternal. She totally saw that man as the same age — he was 28 — as Anne or one of her older daughters. So she is thinking, “Respect your elders; respect authority. The president is speaking.” There’s a kind of inflexibility there.

She was playful. She loved to pull gags on people. At the same time, here she is completely unwilling to bend to let people protest openly at a public event in a public park.

To take the guy’s sign and put in under her feet like a scold? C’mon Ruth, what were you thinking?

KG: If you were sitting beside Ruth at a fireplace, having a cup of tea, what would you want to say to her, having spent a decade studying and writing about her life?

ABW: Wow. I would let her know that that I really did try to be faithful to the person I thought she was.

Patricia Cornwell [the crime writer and close Graham family friend] writes in the preface of her book about coming to Ruth and saying, “I want to write a book [about you].” Ruth was like, “No, don’t waste your time on me.”

I’m guessing that Ruth would say to me, “I don’t know why you spent so much time, 10 years, whatever, and all this angst, worry, stress, traveling around trying to talk to people. Why would you do that about me?”

I would say, “Well, you’re pretty important.”