Who has disappeared from your life because of politics? It’s a tough question, and one that Curtis Chang hopes Christians will reflect upon.

“We are losing each other, both in our individual families, friendships, as well as more broadly as a society. We’re disappearing from each other, and that’s a very dangerous thing,” Chang said.

But even in today’s angry partisan atmosphere, Chang and his co-creators have hope that people can learn to deal with one another differently, even when they disagree.

They’ve created a course designed to help Christians navigate politics with a focus on relationships, which he refers to as the “how” of politics, rather than specific policy or electoral goals, which he calls the “what” of politics. They hope it will be useful to pastors who want to talk about politics with their congregations but don’t know how to start.

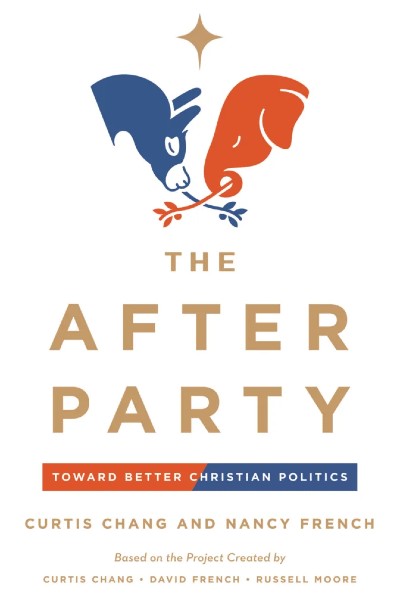

“The After Party,” a free, six-part video course and companion book, features teaching by Chang, a consulting professor at Duke Divinity School and senior fellow at Fuller Theological Seminary; Russell Moore, the editor-in-chief of Christianity Today and director of its Public Theology Project; and David French, an author and New York Times columnist.

The related book, “The After Party: Toward Better Christian Politics,” was co-written by Chang and journalist and author Nancy French. A album of music will be released later this year.

The project is designed for individuals and small groups to discover their own political personas and to better align their approach to politics with Christ’s teachings. By focusing on the how rather than the what of politics, the creators hope to help Christians better navigate the current polarized political environment.

“Christians, of all people, should be ones that can practice a way of engaging in politics that is not captive to the partisan hatreds that currently dominate,” Chang said.

Chang spoke to Faith & Leadership’s Sally Hicks about the course and the book. The following is an edited transcript.

F&L: One thing that’s striking in the book and the course is that you ask people to imagine those who have disappeared from their lives. You tell several stories that are very poignant. What did you hope to evoke with that question?

Curtis Chang: I wanted to [give] a wake-up call to people: “Hey, something awful is happening!”

This should be a warning sign to us that we’re on the wrong path here, and we need to change our path to move toward better Christian politics.

I also think that is where people have the most motivation for change and hope. Because if it’s just this abstract national issue out there, it feels exhausting. It feels hopeless.

But if it’s, “Can I actually recover something about this lost relationship with my uncle, with my grandfather, with my parents?” — that has a meaning.

F&L: Have you had people disappear from your life?

CC: Yes. It’s been very painful. In my own church we’ve lost people — because of politics — that I no longer see anymore. And I’m a former senior pastor of this church. These are people I’ve pastored for years. They’re not there anymore because of political division.

F&L: What do you hope to achieve with this course?

CC: I hope this helps individual people and small groups who are looking for a better way, who realize relational losses that they’ve suffered and are looking for a redemptive path from Jesus to go forward.

I also hope it serves churches and pastors who have been paralyzed because they haven’t had a really good play to run in the last three election cycles.

We are aware that in many contexts, the Sunday morning sermon is not the best place to talk about politics, or certainly to talk about it for the first time. These conversations are best when they’re done in face-to-face, back-and-forth, interactive relationships.

Many pastors have been paralyzed and have just tried to ignore politics, not talk about it, and white-knuckle their way through an election cycle. They’ve realized instinctively, “It’s not going to go well if I try to preach about this on Sunday morning.”

They don’t have an alternative. They end up just being silent. And the problem with trying to ignore it is that spiritual formation abhors a vacuum. People will get spiritually formed, and if it’s not the church and the gospel forming people, it will be Fox News, MSNBC, name your other secular news sources.

One of our great hopes for “The After Party” is to give a play, a tool, for pastors. To say, “You don’t have to preach about it on Sunday morning necessarily, but you also don’t have to just stay silent and just try to hope you can make it through another election cycle. There’s something positive, spiritually formative you can do here.”

F&L: Your course and book are called “The After Party.” What does the title mean?

CC: There are at least three layers of meaning to “The After Party”: the political, the relational and the theological.

At the political level, we are saying, “Let’s call us to a way of engaging in politics that moves beyond, moves after this preoccupation with partisan divides.” We want to move beyond that. We want to go to the after, what comes after that.

There’s also a relational meaning to “The After Party.” The after-party is the small gathering of people you get together after the big event, right? The meaningful conversations happen in the smaller, more intimate gatherings, where we are gathered together in small groups, in Bible studies, at prayer breakfasts, and with friends or families.

That’s why we’ve designed the curriculum of “The After Party” to be something that is used in our most intimate, embodied communities. That’s another meaning of “The After Party”: “Let’s get away from all the hubbub and the hot headlines that can be so distracting and divisive, and let’s hang out together again.” Our curriculum equips people to talk meaningfully, talk substantively, but to do it in a way that is face-to-face, in a relational context. So that’s the relational meaning of “The After Party.”

The third is theological, which is to remind ourselves that all human partisan efforts, all human political parties, will never solve the problems that we want to be solved. They will never restore all the things that are broken. They will never stave off all the losses we fear.

To place that expectation and weight on the Republican Party or the Democratic Party is to miss where Christian hope is located. The core of our Christian hope is we do have a political ruler, Jesus, the King, the Lord, who will come back to restore all things, to actually restore all of our feared losses, to restore justice — to restore, to reconcile us in all things.

And when Jesus returns to do that, the Scriptures are clear that it will be like a party. It will be a great party, a great feast. And that’s the after-party.

F&L: One thing that people might be surprised by is that the book and course don’t actually talk about politics in the way one might expect.

CC: In the course, we don’t mention any of the candidates or the parties, because we’re talking about the how. We’re not talking about the what.

It depends on how narrow a definition of politics you have. When we use the word “politics,” we have overwhelmingly narrowed that definition to mean the what of politics. What party is the most Christian party? What candidate should we vote for as Christians? What ideology is the more Christian ideology?

It’s a bunch of whats, right? That is part of politics, but politics is as much about the how: How do we relate to people? How do we relate across differences? How do we feel about things when we lose on the what? How sure are we that we’re right on the what?

We’re telling Christians to say, “Christian politics needs to recapture emphasis on the how, not just the what.”

Jesus is far more clear on the how than he is on the specific whats. If you read the Sermon on the Mount and you want to draw a line from Jesus’ teaching in the Sermon on the Mount to a specific policy on Gaza, what our climate change policy should be, what our border policy should be, it’s fine and legitimate to try. But at best, you’ll be drawing a fuzzy line. It’s going to be fuzzy, and it’s going to be contested.

Now, when you talk about the how, Jesus is very clear in the Sermon on the Mount: Do not engage in malice. Do not call your opponents idiots, fools, or raca [a term of contempt]. He says to seek reconciliation above winning at all costs.

Practice mercy. Love mercy. Make peace.

These are all clear how-actions, how-behaviors, how-values, and you can draw a very straight line from Jesus’ teaching in the Sermon on the Mount to how-behaviors in politics today. It’s clear. It’s uncontested. And it applies to all the colors that you might wear in terms of partisanship.

F&L: What’s the how you want Christians to practice?

CC: Our course is really anchored on two big how-virtues that Jesus teaches as paramount in any disciple’s engagements in life, and particularly in politics. And those twin virtues are hope and humility.

How do we move people toward greater hope and humility? We give people a quiz at the beginning of the course that helps them self-evaluate. The Hope and Humility Conversation Starter gives people a way to locate their starting point and then [find] their growth path toward becoming a deeper disciple.

When you put hope and humility in a 2-by-2 grid, with hope on one axis and humility on the other axis, you end up with four quadrants. And those four quadrants end up being the dominant profiles of how people engage in politics.

Somebody that is high in hope but low in humility — that’s [who we call] the Combatant. A combatant is hopeful; that’s why they’re fighting. They think they can win. They just think they’re right and the other side is wrong.

Then you go to the mirror opposite, and you talk about somebody who is high in humility — they’re not sure they’re right — and low in hope. That’s who we call the Exhausted.

It turns out, the exhausted actually make up the majority of both Christians and Americans, but the combatants actually have the most influence, because they care the most and they are the most engaged and speak the loudest.

And then you talk about the third quadrant, which is low in humility and low in hope. That’s the person we call the Cynic, because the cynic is somebody who thinks they’re right, and what do they know better than everybody else? That it’s hopeless.

This diagnostic entry point into the course enables everybody to identify themselves on a growth path toward [the fourth quadrant] — the Disciple. The disciple is somebody who is high in hope and humility. A disciple is literally a learner.

We are not defining ourselves in opposition to each other on the whats, because you can be a Republican Exhausted or a Democrat Exhausted. You can be Republican Combatant, a Democrat Cynic and so forth.

We lead them in the course to talk about, “What does it mean to be exhausted? Regardless of your belief about how the posture of being exhausted looks, what is it like?”

F&L: Is your theological approach influenced by your tradition? How?

CC: I would say theologically we are very orthodox, classically orthodox, or if you want to call it evangelical in the classic historic sense of that word, the theological definition of the word “evangelical,” very much so.

Our theological tradition is centered on “Jesus is Lord.” That is the core, which is a political statement, right? It is very much anchored in our theological tradition to say Jesus is the Lord of lords, and therefore all these petty lords — whether you call them by the names of Herod, Caesar, the Zealots or Republican or Democrat — all of our allegiances to those smaller lords have to be subsumed, have to be subservient to the Lord of lords.

Which means that even if it seems like loyalty and fidelity to Jesus on the how may not necessarily lead to victory on the what, we’re faithful to the Jesus-how, which is the exact opposite of where I think too much of Christianity has gone, which has been to sacrifice the Jesus-how in order to win on the human political-what.