David P. Gushee thinks that Christians should support democracy.

That idea might once have seemed obvious, at least to American Christians. But, as Gushee argues in his new book, their support is wobbling. Indeed, he writes, Christians who favor authoritarian and reactionary politics “turn out to be among the leading threats to democracy in much of the world.”

“We have,” he said, “what has to be described as a radical change in a part of the Christian population that is willing now to entertain the abandonment of disestablishment and the separation of church and state” paired with “the use of state power to advance the specific traditionalist Christian vision and to suppress those groups that have won their freedom.”

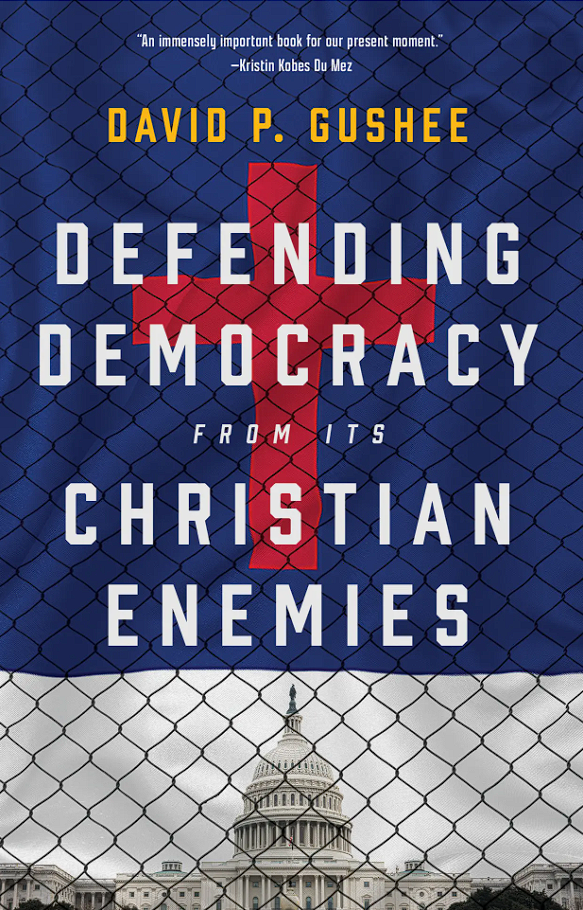

In his new book, “Defending Democracy From Its Christian Enemies,” Gushee explores the history of Christians’ anti-democratic leanings and examines why what he calls “authoritarian reactionary Christianity” is on the rise.

He also names the ways in which Christians, and the Christian tradition, have upheld and can uphold democratic ideals.

Gushee is Distinguished University Professor of Christian Ethics and the director of the Center for Theology and Public Life at Mercer University. He has an M.Div. from Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and a Ph.D. and an M.Phil. from Union Theological Seminary.

He spoke to Faith & Leadership’s Sally Hicks about his new book. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: You write about being brokenhearted with the situation today as a Christian and as an American. It struck me, in a book like this, as very touching and very real.

David P. Gushee: I remember Richard Nixon. I remember the divisions over Vietnam. I’ve seen the rise of the Christian right. I’ve seen closely contested elections and bitterly divided Americans.

But the rise of Donald Trump, and what I would describe as the moral devolution of his Christian followers, the rhetoric and practice of political violence as a routine feature of our politics, the assault on the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021 — all of these feel categorically worse than anything I have witnessed before.

This book is very analytical, and it’s attempting to deal with issues of public policy and politics at a high level intellectually. But the heartbeat of the book is, “How did we get here? What went wrong? And can we dig ourselves out of this hole that we find ourselves in?”

There is a visceral pain that motivated the writing of this book.

F&L: Could you define the term “authoritarian reactionary Christianity,” which is the core concept in the book?

DPG: The first term that is significant is “reactionary.” My proposal is that Christians in the West — Europe and the U.S. — have demonstrated a long-standing tendency to position themselves as reacting harshly, negatively, to cultural developments that they don’t like. This goes back to the very beginning of the modern world, the very birth of modern democracy and the liberalizing trends in culture, maybe as far back as the Enlightenment.

If the story that Christians tell is that modernity is rebellion against God, that modernity in Europe and the U.S. involves formerly Christian civilizations rejecting God and God’s law and embracing godless secularism and liberalism, then every modern cultural development is viewed negatively.

The women’s movement, the civil rights movement (if people are willing to be honest about that), abortion rights, the gay rights movement, the sexual revolution, the racial and ethnic pluralizing of American culture, the Supreme Court decisions setting limits on prayer and Bible teaching in public schools — you name it, right?

But if you go back further, there was a negative reaction to the emancipation of Jews, for them to have political rights, for example. Democracy itself was seen as throwing off God’s plan for monarchical Christian regimes.

Everything modern is bad.

Political authoritarianism is the embrace of nondemocratic forms of government and politics such as dictatorships, autocracies, oligarchies, monarchies, or just the compromise of democratic checks and balances and principles.

Authoritarianism in religious life is the idea that a centralized authority tells us what is right, good and true religiously, whether it’s a pope or cardinals or bishops or a pastor, a tradition. The role of the people is to submit to the authority that comes from above.

When Christians, motivated by negative reaction to modernity, start flirting with authoritarianism and casting doubt on democracy, they can contribute badly to the erosion of democracy. That’s the story that I’m telling.

You can be reactionary without being authoritarian. You can be reactionary without being Christian. You can be authoritarian without being Christian. But you put it all together — reactionary Christians embracing authoritarianism, bringing it into politics and contributing to democratic erosion or backsliding — that’s happening in the U.S. But it’s also happening in other countries as well.

F&L: You analyze what’s happening in countries such as Russia, Brazil, Poland, Israel. But we Americans think of ourselves as different. Are we?

DPG: I think that part of the extraordinariness of this moment is that we were different. We were different in our founding, different in the arrangements we set up for the relationship between church and state.

We had a fairly stable paradigm going back to 1789, which was that America was a religiously diverse country and the government would take a position of neutrality in relation to people’s religious choices, would protect the free exercise of religion.

Though the government would not help you practice your religion by collecting tax dollars for you, the government would provide freedom for the practice of religion and would not establish one religion as the religion of the land.

That’s not what happened in Europe. In Europe, you had state churches. And so you would think that the story would be different.

But since the ’60s, a different, shared narrative has overwhelmed older narratives. And the shared narrative is the story of dramatic cultural liberalization evoking dramatic negative Christian reaction and of politicians in multiple different countries leveraging Christian outrage to come to power.

They promise traditionalist Christians that their values will be protected and promoted, and [promise] to attack those groups whose greater rights and greater recognition have been gained in the last 50 or 60 years.

What these reactionary movements all tend to have in common is attacks on recently liberated groups or recently included groups, like women, divorced people, Jews, Muslims, atheists, immigrants, racial minorities who had been suppressed, gay people, etc.

And to say, “The problem is these people are all around us doing what they want to do in violation of the Christian values that ought to dominate the society. Trust me, turn to me, vote for me, support me, and I will suppress them and put them back in their proper place.”

And if that means that democratic civil liberties and processes have to be compromised to do that, then that’s a price worth paying.

F&L: You name some Christian traditions that offer a kind of hope. The Baptist tradition, for example. How can Christianity contribute to democracy?

DPG: We kind of took for granted our democracy and thought it had always been there, would always be there, and that Christians, like everybody else, would be supporters of democracy.

But now we have to renew the argument for why Christians should support democracy. We have to make the case again, because people are not so sure they believe it anymore.

That does speak, by the way, to deep disillusionment with the performance of our democracy and our overall cultural disillusionment with the institutions of our society: Supreme Court, Congress, presidency, media, higher education, you name it.

You can begin to see stirrings in the 17th century with the Republican movement under Cromwell in England, in the 18th with the revolution in France and the revolution in the U.S., and what happened in the 19th and 20th centuries, the democratization of Europe and of the Americas. How did Christians come to terms with this?

While some Christians didn’t come to terms with it, most did, and certain groups helped lead the way. One of them that I profile is the Baptists. And I happen to be a Baptist, have been for 45 years.

The Baptists were among those who argued for religious liberty, for limited government, for the state getting out of the religion enforcement business, for human rights, for toleration. And for an understanding of the nation as a covenant, but not a covenant based on religious conformity — a covenant based on a broader sense of concern for the common good and loyalty to the nation and to one another.

In the U.S., the Baptists demanded separation of church and state and religious disestablishment as a condition of their support for ratification of the Constitution, one of the best Baptist contributions in all of history.

I also talk about the value of congregationalism in general and democratic practice. People learned to rule themselves in congregations that they established, writing covenants for themselves, deciding what membership would mean, deliberating, debating and voting on matters involving the people in the church, electing leaders, deposing leaders, electing new leaders. Congregations have been laboratories of democracy.

I urge the readers to look around at any association that they’re involved in where they get to participate democratically and to see it as valuable, a school of democracy. It could be a book club. It could be a congregation, it could be a bowling league, it could be the Boy Scouts — whatever it is, a structure where we get to participate.

You see it with the Reformed folks too, the Calvinists, as they thought the church does not flow from the monarch down to the people but the church is something that is created by the people from the ground up. I think modern democracy is inconceivable apart from congregational Christianity. And that preceded the work of political philosophers like John Locke.

It’s also a richer vision of community. People form congregations because they have a vision of community. They have a vision of what kind of godly community they want to create, or they want help in following Jesus and building healthy Christian community.

In other words, they have a vision of the good. And this is something that Christians can bring into modern understandings of democracy too. We participate as democrats, little d, in society because we care about our neighbors and we care about the common good of all.

In the West, democracy partly takes its origins from Christians trying new ways of governing themselves and Christians arguing, “We have demonstrated that we can govern ourselves; let us form our own polity in which we govern ourselves.” And that’s the birth of the United States of America.

Now, it was deeply flawed. Racism and slavery damaged American democracy from the beginning. But the roots of self-rule are to be commended and then extended to include everybody. Instead of interpreting every development since the 1960s as a negative reaction in a negative way, a better way to interpret a lot of what has happened since the 1960s is more and more people being included in the community on equal terms. That is in keeping with democracy, and Christians ought to be able to support that.

F&L: You also write about the Black church tradition and democracy.

DPG: White Christian America was blinded by racism, so that the original national covenant did not include nonwhite people, certainly not on equal terms. And that flaw haunts our country from the beginning, sometimes called America’s original sin.

When African Americans embraced Christianity beginning in the 17th century, even though they were taught Christianity by those who enslaved them at first, a significant number of them reworked Christianity to challenge the white supremacy and the slaveholder theology.

And as they gained political rights and as they pressed for political rights, they were able to articulate very early that American democracy was flawed from the core because it did not include them.

And so you might say the best democrats and the earliest democrats in American history were enslaved people and formerly enslaved people who said, “Your democracy needs to be reformed so that its true principles can be practiced and that everybody can be included.”

Sometimes this is called abolitionist Christianity; sometimes it’s called Black social gospel Christianity, when you take it into the early 20th century. It’s W.E.B. Du Bois and Frederick Douglass and Ida Wells-Barnett and Martin Luther King Jr. and James Cone and Cornel West and Fannie Lou Hamer and James Baldwin, one of my favorites, saying, “It is time for you to live out the true meaning of your creed and include everybody on equal terms.”

Black Christian democratic activism is a uniquely American Christian phenomenon that teaches us a lot about what it means to fight for democracy. You don’t have to be native born to be a citizen. You don’t have to be white to be a citizen; you don’t have to be male; you don’t have to be a property owner; you don’t have to be straight; you don’t have to be Christian. You’re a part of this community. I believe that that is good progress.

We’re still fighting a struggle that goes back 400 years: “Who is a member of this covenant community called the United States of America?”

Authoritarian reactionary Christianity is deeply inflected by white supremacy and a desire to really reverse the inclusive enfranchising of more and more parts of our population.

F&L: What do you think is going to happen, and what do you hope will happen?

DPG: I’ll just say it directly: Trump has to be defeated, either in the primaries (and it would be nice if the Republicans would repudiate him themselves) or in the general election. And he needs to retire from the political scene to give Republicans a chance to recover themselves and start over.

In 2022, a number of mini-Trump-type candidates ran for major offices, and pretty much all of them lost. And that was encouraging to me. I’m hoping that when faced with the choice between authoritarianism and a backward, white, ethnodemocratic or nondemocratic vision, and a vision of inclusive, multiracial democracy in which everybody gets a place, I’m hoping we will choose the latter.

What I fear is going to happen is the opposite — that he somehow becomes president again and now, with greater determination and greater information as to how to cut the checks and balances into shreds and how to weaken democracy, will set to work doing that one step at a time, the way some of the other demagogue figures have already done in other countries.

I don’t know what’s happening in November. I fear a very difficult political year. I fear another contested election. I fear political violence. And all of that connects to that sense of heartbreak.

I want Americans to choose democracy and to renew democracy. We need a renewal of democracy. We need to fix some things, have our democracy operate more effectively, but we have to choose democracy to do that. And that’s what I hope will happen.